09/2005

by

Russell Boniface

by

Russell Boniface

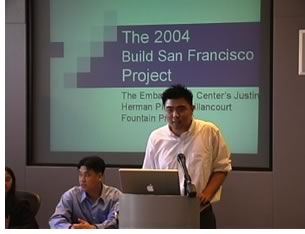

The Architectural Foundation of San Francisco (AFSF) runs an exemplary program called the Build San Francisco Institute (BSFI), a response to the growing need for rigorous and relevant programs for today’s high school students. Created in 2004, the program is part of the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) Secondary School Redesign Initiative. The Build San Francisco Institute is the result of more than 10 years of effort on the part of the AFSF and grew from a small, summer mentorship program into a fully accredited half-day high school program. Funding is shared by AFSF and SFUSD.

The program is open to any SFUSD junior or senior from high schools throughout the city. Its enrollment reflects the diversity of San Francisco, with students of varied backgrounds and abilities. Projected enrollment for the program this fall is over 40, with 35 students currently pre-enrolled. Each semester, students take two courses, “Issues in Urban Sociology” and “Architectural Design.” Many students take two full semesters, completing 10 units in each course. Students meet during school hours in the afternoon.

Coursework is approved by SFUSD and meets University of California admissions requirements, and the grades appear in the students’ high school transcript. The district provides a credentialed teacher and curriculum materials, as well as support for student services. In addition, students can earn an additional five units per semester through their mentorship experiences, which is about six to eight hours of service time per week. AFSF, in turn, organizes and manages the program, with mentors coming from the San Francisco design, engineering, and construction community.

School makes sense

“The program exemplifies the education philosophy of the Architectural

Foundation of San Francisco,” says Will Fowler, program director

of AFSF. “It stresses that the world of design allows students to

integrate all of their academic studies into a meaningful whole. For example,

the program enables students to understand the real-time constraints of

development and project planning. High school students live in a world

of ‘300 words due Friday,’ or ‘problems 1–20 due tomorrow,’ that

is, they complete short assignments and move on through the curriculum.

Projects planned, developed, and completed over the course of several years

is a new way of thinking for them. BSFI emphasizes that process and models

it in the coursework we give the students.”

Fowler

points out that the partnership with SFUSD helps put AFSF in the mainstream

of school reform efforts, so the Build San Francisco Institute program

helps students gain a better understanding of the relevance of the more

abstract academic subjects they study in school. “A strength

of the BSFI approach is that students see adults making use of mathematics,

language arts, social science, and science skills. Physics, trigonometry,

calculus, earth science—all of these subjects become much more concrete

and seem more useful. History comes alive as they look at the development

of the city over many years or see examples of classical architectural

styles in modern buildings. The ability to communicate ideas with words

and images becomes important. In short, for many students, for the first

time, school makes sense.”

Fowler

points out that the partnership with SFUSD helps put AFSF in the mainstream

of school reform efforts, so the Build San Francisco Institute program

helps students gain a better understanding of the relevance of the more

abstract academic subjects they study in school. “A strength

of the BSFI approach is that students see adults making use of mathematics,

language arts, social science, and science skills. Physics, trigonometry,

calculus, earth science—all of these subjects become much more concrete

and seem more useful. History comes alive as they look at the development

of the city over many years or see examples of classical architectural

styles in modern buildings. The ability to communicate ideas with words

and images becomes important. In short, for many students, for the first

time, school makes sense.”

Rincon Towers video study

Last spring, the issue of affordable housing among the students arose

as a result of a conversation the students had regarding their own

futures in San Francisco. This led to the Rincon Towers Project,

a student-directed, 45-minute documentary video study of issues surrounding

the development of new, luxury, 60-story condominiums in San Francisco.

The Rincon Towers are to be built in a two-square-mile warehouse section

South of Market Street in the Rincon Hill district, close to the San

Francisco Financial District. Students received additional funding

for the video project from the Providence organization What

Kids Can Do.

“In an era of high rents and a tight job market, students voiced a concern that there is no place for them in the city of their birth,” explains Fowler. “Most students are worried that they will never be able to afford to live in San Francisco. As a result of their discussion, the students decided to do an in-depth investigation of housing development in the city. The Rincon Towers Project was the result of that investigation.”

Like

many urban development projects, the Rincon Hill development project

isn’t without controversy. It was approved in February 2004 after three

years of political fighting and will consist of two developments, each

with two slender, 500-foot towers, developed by Union Property Capital,

Inc., and Tishman Speyer Properties. The towers were granted a zoning

exception to accommodate their height, almost twice the limit the city

normally allows. As many as 10 towers could eventually be built at the

site. Opponents argued that this would dramatically alter the city skyline.

Detractors also contested the city’s plan to invest city resources

into the project to attract wealthy, biotech professionals as residents.

Supporters believe that the project does allow for higher-density, high-rise

housing, and will be in concert with the city’s vision for the Rincon

Hill area.

Like

many urban development projects, the Rincon Hill development project

isn’t without controversy. It was approved in February 2004 after three

years of political fighting and will consist of two developments, each

with two slender, 500-foot towers, developed by Union Property Capital,

Inc., and Tishman Speyer Properties. The towers were granted a zoning

exception to accommodate their height, almost twice the limit the city

normally allows. As many as 10 towers could eventually be built at the

site. Opponents argued that this would dramatically alter the city skyline.

Detractors also contested the city’s plan to invest city resources

into the project to attract wealthy, biotech professionals as residents.

Supporters believe that the project does allow for higher-density, high-rise

housing, and will be in concert with the city’s vision for the Rincon

Hill area.

According to Michael J. Antonini, a member of the San Francisco City County Planning Commission and member of AIA San Francisco, $25 per square foot from the Rincon Towers project will go toward civic amenities, which have been broadly defined as improvement of streetscapes, schools, parks, libraries, the adjacent Mission District, and other areas South of Market. “The lion’s share will go to the Mission District,” says Antonini. “That is controversial because some people felt the money should be spread citywide. Even though this development isn’t in the Mission District, which has been improving, groups there who already felt they were being displaced because of higher rents or fewer rental units are now saying ‘because we have a problem and because we are on the same side of the city as Rincon Hill, then they should have to pay for our pre-existing problem.’”

Antonini explains that in San Francisco, when a developer gets approval for a project, it must provide back to the community 12 percent on the sale of units to residents who do not exceed 100 percent of the area’s median income. For rental properties, it is 60 percent. “Rincon Hill is above and beyond that with the $25 per square foot it will put toward civic improvements. Nonetheless, many argued it should be a higher percentage.

“We don’t have a lot of land, but what we do have left should

be individualized homes for families. I don’t think any families

are going to buy these places and drag their kids to the 35th floor.

But all the funding is drying up for public housing, especially since

there is not a lot of commercial activity going on right now, so approval

of for-sale projects will allow monies to go to affordable housing and

other city amenities. In the end, it’s business that is going to

drive the engine. You can only soak the tourists and homeowners so much,

and many companies have moved outside the city limits to avoid a payroll

tax. The irony is that the middle class is at risk of being driven out

because they are making too much to be subsidized but not enough for

the regular, market-rate units.”

“We don’t have a lot of land, but what we do have left should

be individualized homes for families. I don’t think any families

are going to buy these places and drag their kids to the 35th floor.

But all the funding is drying up for public housing, especially since

there is not a lot of commercial activity going on right now, so approval

of for-sale projects will allow monies to go to affordable housing and

other city amenities. In the end, it’s business that is going to

drive the engine. You can only soak the tourists and homeowners so much,

and many companies have moved outside the city limits to avoid a payroll

tax. The irony is that the middle class is at risk of being driven out

because they are making too much to be subsidized but not enough for

the regular, market-rate units.”

Students videotape their exploration

The Build San Francisco Institute students interviewed many of the principal

parties involved in the Rincon Towers Project development, design,

and engineering, including politicians and CEOs of the property companies

behind the Rincon Towers project. The students documented their travels

with video cameras.

“They met with members of the planning department to understand how this project fit into the growing need for housing in San Francisco,” describes Fowler. “And they spoke with opponents of the development in an effort to understand why the project had generated so much controversy. Through their research, students learned the process of urban development, the requirements of city planning, and the choices that a city must make in planning a sustainable community. Students felt they had a clearer understanding of the process of development. At the same time, they remained concerned that entry-level housing was still a major need in the community.”

The

video is divided into 11 parts, posing questions such as whether San

Francisco can afford a new high-rise neighborhood, why build Rincon Hill,

are developers ignoring civic obligations, should market forces dictate

the supply of residential housing in San Francisco south of Market Street,

and who would be served by the development and why. The documentary also

explores the cost of construction, housing prices, and the problems and

positives of developing on Rincon Hill. Students researched, wrote, filmed,

edited, narrated, and starred in the video.

The

video is divided into 11 parts, posing questions such as whether San

Francisco can afford a new high-rise neighborhood, why build Rincon Hill,

are developers ignoring civic obligations, should market forces dictate

the supply of residential housing in San Francisco south of Market Street,

and who would be served by the development and why. The documentary also

explores the cost of construction, housing prices, and the problems and

positives of developing on Rincon Hill. Students researched, wrote, filmed,

edited, narrated, and starred in the video.

“Every adult who has seen the video is impressed by its clarity of thought and the professional manner in which the students created the program,” says Fowler. “It is seen as a comprehensive and balanced report on a key issue in San Francisco.”

David Alumbaugh, senior urban designer of the San Francisco Planning Department, says that the planning staff enjoyed their experience interacting with the students. “They had a wonderful energy and inquisitiveness,” he says. “They wanted to learn about all aspects of the project and the planning of the Rincon Hill neighborhood, from the planning and permitting to the development.” Alumbaugh adds that students were interested in the community's concerns and response to the plan. “The students challenged us to think about how we could ensure that the place was built for people at all income levels. They also brought the perspective of youth--a viewpoint that is often missing from many planning processes. And having an active group questioning us on what we were doing helped to keep our work even more focused on the livability aspects in the plan. Hopefully, a few new urban planners were hatched by the experience.”

“Rincon Towers” will screen at the San Francisco City Planning Commission and is also scheduled to be shown at student film festivals and grassroots organizations.

Clearer understanding of architecture

Clearer understanding of architecture

Fowler notes that his organization has helped open the eyes of the students

about architecture and civic responsibility. “Our students report

that, for the first time, they are thinking deeply about the development

of the community and its needs. They report a much clearer understanding

of how architecture really happens and the process of urban development.

And, by studying real-world design problems, they are not only improving

their academic skills but also they are becoming deeply involved in

important community issues.”

AFSF will remain committed to developing the Build San Francisco Institute program, and Fowler hopes it can be a role model to other architecture organizations on how to set up and run mentoring programs. “We feel that we have a unique program. The combination of academic study, design experience, and mentorship in the field is a powerful combination for our students. To the best of our knowledge, there is nothing quite like our program available in other cities. As we develop our local program, we will be looking for ways of sharing our experiences with interested communities around the country.”

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

Sidenote: On August 20th, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that the developers of the four Rincon Towers, Union Property Capital, Inc. and Tishman Speyer Properties, are planning to pay $50 million in additional fees as compensation for South of Market residents who will be affected by the project. Did

you know…

|

||