08/2005

by Jonathan Moore

It’s a truism worth remembering: Giving one’s time and talents to others begets unexpected rewards. Moreover, for architects as well as all professionals, pro bono work is an integral component of professional practice. As the AIA Code of Ethics & Professional Conduct states, “Members should render public interest professional services and encourage their employees to render such services.” Thus, it is no surprise that AIA members, through their components and architectural foundations, have organized to provide communities with abundant pro bono services.

Pro bono services are those rendered without compensation or expectation

of a fee for the public good. There are rewards, however, both tangible

and intangible, not the least of which is the satisfaction of giving

back to the community. On a more material level, pro bono work brings

with it increased firm-name recognition, a better public understanding

of the value of the profession in general, valuable strategic contacts,

and overall, therefore, business development.

Pro bono services are those rendered without compensation or expectation

of a fee for the public good. There are rewards, however, both tangible

and intangible, not the least of which is the satisfaction of giving

back to the community. On a more material level, pro bono work brings

with it increased firm-name recognition, a better public understanding

of the value of the profession in general, valuable strategic contacts,

and overall, therefore, business development.

With increased attention to benefits derived by the general public, pro bono practice is making its mark from coast to coast. For example, architects are revitalizing neighborhoods, schools, and parks in our nation’s capital under the AIA/DC Community Design Services (CDS) program. Directed by the chapter’s Washington Architectural Foundation (WAF), CDS pairs architects with local nonprofits to prepare preliminary designs and other forms of technical assistance. Expert guidance includes cost estimates, zoning analysis, conceptual models, and other visionary ideas for structural and landscape renewal. “CDS is a key component of our outreach mission,” says WAF Board President Stephen J. Vanze, AIA. “Through its collaborative efforts, architects are restoring many of Washington’s hidden treasures.”

A spirit of brotherly love is abundant in greater Philadelphia as well, with architects, engineers, and other design professionals volunteering with the Community Design Collaborative. Created by a handful of volunteers in 1991, the collaborative began as a special initiative of AIA Philadelphia, became an independent nonprofit entity in 1996, and currently places more than 100 design professionals with local nonprofits each year. The collaborative offers preliminary design assistance such as structural and mechanical assessments, conceptual design, cost estimates, and programming and space planning. Each year the collaborative provides an estimated $5,000 to $15,000 in non-billed services. Like CDS, the collaborative provides architects with outlets to test and convey their visions for community environmental renewal.

In some cases, projects under both programs can lead to actual billable work. “Design firms support the collaborative because it offers professional development and the chance to bring design into the neighborhood arena,” says Beth Miller, the collaborative’s executive director. “Our volunteers’ early involvement provides leverage for additional grants and services that take the project to the next step in the development process.”

Serving the public

In San Francisco, pro bono requests from Bay Area nonprofits were piling

up on the desk of John Peterson, principal of Peterson Architects.

(See the member spotlight). Receiving

a broad spectrum of project requests, Peterson discovered his firm’s

pro bono workload began exceeding billable orders. This resulted in

his firm’s creation of Public Architecture, a 501(c)3 nonprofit

organization putting architectural resources in the service of the

public interest. Offering creative solutions for practical problems

associated with the built environment, Public Architecture seeks to

move architecture beyond time-honored guidelines of conventional practice,

providing a stable venue for experimentation and exploration.

“Public

Architecture’s nonprofit clients are often initial

recipients of new ideas and design concepts,” says Peterson. “Its

operating structure helps design professionals become more proactive

with problem identification and creative solutions through innovative

research, new technologies, and creative application concepts.” Rather

than waiting for commissions with predefined tasks, a central tenet of

Public Architecture’s mission is creating more of a leadership

role for architects as problem identifiers—complementing their

more established role as problem solvers. Peterson believes pro bono

work will help architects remain competitive with other professions well

known for community service. “Architects nationwide are contributing

in many ways to benefit our daily lives,” he adds. “We

just need to leverage more instances of public recognition in support

of our efforts.”

“Public

Architecture’s nonprofit clients are often initial

recipients of new ideas and design concepts,” says Peterson. “Its

operating structure helps design professionals become more proactive

with problem identification and creative solutions through innovative

research, new technologies, and creative application concepts.” Rather

than waiting for commissions with predefined tasks, a central tenet of

Public Architecture’s mission is creating more of a leadership

role for architects as problem identifiers—complementing their

more established role as problem solvers. Peterson believes pro bono

work will help architects remain competitive with other professions well

known for community service. “Architects nationwide are contributing

in many ways to benefit our daily lives,” he adds. “We

just need to leverage more instances of public recognition in support

of our efforts.”

All they ask is one percent

Inspired by formalized systems in the legal and medical professions encouraging

pro bono service, Public Architecture launched its One

Percent Solution program on April 1. Led by Executive Director

John Cary, Assoc. AIA, the One Percent Solution challenges architecture

firms and individual practitioners to dedicate a minimum one percent

of their working hours to pro bono service annually. Growing from Cary’s

belief that design professionals lack encouragement and support nationwide

needed to record pro bono work, the One Percent Solution establishes

measurement goals itemizing architecture’s contributions to their

states and localities. “Pro bono should be viewed not as free, but for the public good,” says Cary.

Public

Architecture calculates that one percent of the standard 2,080-hour work

year would total 20 pro bono hours per annum, representing a “modest,

but not trivial, individual contribution to the public good,”

according to Peterson. Cary readily acknowledges certain nuances associated

with pro bono practice: documenting non-billable hours, pursuing untested

design concepts, and greater reliance on Good Samaritan liability laws

to name a few. With rewards outnumbering potential liabilities, Public

Architecture believes pro bono work promotes an intrinsic value of practice,

as well as political clout vis-à-vis other licensed professions. “Adoption

of One Percent’s goals and objectives by firms large and small

will further enhance architecture’s ability to compete in the public

relations and public policy arenas,” Cary adds.

Public

Architecture calculates that one percent of the standard 2,080-hour work

year would total 20 pro bono hours per annum, representing a “modest,

but not trivial, individual contribution to the public good,”

according to Peterson. Cary readily acknowledges certain nuances associated

with pro bono practice: documenting non-billable hours, pursuing untested

design concepts, and greater reliance on Good Samaritan liability laws

to name a few. With rewards outnumbering potential liabilities, Public

Architecture believes pro bono work promotes an intrinsic value of practice,

as well as political clout vis-à-vis other licensed professions. “Adoption

of One Percent’s goals and objectives by firms large and small

will further enhance architecture’s ability to compete in the public

relations and public policy arenas,” Cary adds.

Notable examples

A visit to the One Percent Solution

Web site reveals architecture’s

creative imprimatur on a variety of projects. For Hands-On Atlanta, a

nonprofit volunteer placement group, an unscheduled move led to “charrette-like” purchase

of an old seafood distribution warehouse. Roy Abernathy, AIA, and his

team with Atlanta’s

Jova/Daniels/Busby Architects offered to help. Abernathy and his crew

outlined what he terms a “low-impact comprehensive plan taking

advantage of the idiosyncrasies and unusual character of the building.”

Transforming a fish warehouse facility to administrative offices included

installation of high-efficiency light fixtures, overhauling water and

ventilation systems, and use of “gently worn” carpet and

furniture from major corporate donors. Abernathy extols pro bono’s

virtues, believing it establishes “collateral credibility” for

design professionals on many levels. In his view, this credibility translates

into more effective advocacy before zoning boards, code enforcement agencies,

urban planning councils, and other design and construction sectors.

Transforming a fish warehouse facility to administrative offices included

installation of high-efficiency light fixtures, overhauling water and

ventilation systems, and use of “gently worn” carpet and

furniture from major corporate donors. Abernathy extols pro bono’s

virtues, believing it establishes “collateral credibility” for

design professionals on many levels. In his view, this credibility translates

into more effective advocacy before zoning boards, code enforcement agencies,

urban planning councils, and other design and construction sectors.

And in the nation’s capital

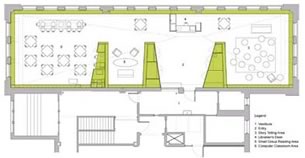

In Washington, D.C., preliminary plans call for converting an abandoned

1950s-era movie theater into a multipurpose community center thanks

to a CDS team led by Leora Mirvish, AIA, of Quinn Evans Architects.

Working with D.C.’s Far Southwest-Southeast Community Development

Corporation, 12,000 square feet of existing space would be remodeled

into retail shops, small offices, and rooms with retractable walls

for community events. Blueprints even include adding four one-bedroom

rooftop apartments. Another CDS volunteer, Carlisle S. Bean, AIA, is

providing conceptual interior/exterior upgrades to an 80-year-old semi-detached

row house on behalf of MOMMIES TLC (Mentors of Minorities in Education),

which provides after-school and summer programs for disadvantaged children

in Washington’s Columbia Heights neighborhood.

Bean’s

efforts include checklists for zoning, life-safety, building code, and

ADA-accessibility requirements, and a schematic design for expansion,

which could incorporate recycled or donated materials such as steel posts

and beams. In the spirit of sustainable design, he is also advocating

grass-covered rooftop areas, rainwater entrapment, and possibly, solar

water heating. These proposed additions could help qualify for LEED™ certification

by the U.S. Green Building Council, making this row house a notable

architectural model as well as a first-rate learning center for children

and the neighborhood.

Bean’s

efforts include checklists for zoning, life-safety, building code, and

ADA-accessibility requirements, and a schematic design for expansion,

which could incorporate recycled or donated materials such as steel posts

and beams. In the spirit of sustainable design, he is also advocating

grass-covered rooftop areas, rainwater entrapment, and possibly, solar

water heating. These proposed additions could help qualify for LEED™ certification

by the U.S. Green Building Council, making this row house a notable

architectural model as well as a first-rate learning center for children

and the neighborhood.

A project manager with Washington’s WDG Architecture PLLC, Bean is a seasoned pro bono veteran, having participated in AIA Regional Urban Design Assistance Teams (R/UDAT). He views pro bono work as essential for building public appreciation of the true scope and complexities of the profession. “Architects are not just designers, but an integral part of the entire building process,” he says, pointing out the keen eye and unique approach design professionals contribute to their client’s objectives. Bean volunteered for CDS at the urging of WDG principal C.R. George Dove, FAIA, an ardent proponent of community outreach and former president of the Washington Architectural Foundation.

You can do it, too

Benefiting from increased public exposure as new ideas come to life has

many architect’s singing pro bono praises. Through programs like

Community Design Services, the Community Design Collaborative, and

Public Architecture, cost analysis and image projections are being

transformed into virtual reality. “CDS serves as a catalyst for

concept projects that might not otherwise be considered,” says

Mary Fitch, AICP, WAF executive vice president and AIA/DC executive

director. “Expanding community outreach to local nonprofits is

what energizes our foundation, and through CDS, these activities provide

tangible blueprints for fundraising initiatives, while showing other

potential stakeholders a project’s future potential.”

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()