08/2005

by Lt. James Vandenberg, AIA, CEC, USNR (Seabees)

Lt. Vandenberg recently

returned from 10 months in Iraq as a “combat

architect” with the First Marine Expeditionary Force (IMEF) in

Al Anbar Province, western Iraq. He was called to active duty from his

job as state architect for the Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism.

He was tasked with working with local sheiks to determine their construction

needs in Al Fallujah, Ar Ramadi, and later on the western border with

Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia from the Al Asad Forward Operating Base.

What came out of these meetings, he tells us, was a need to design and

construct hospitals, schools, and security projects.

Lt. Vandenberg recently

returned from 10 months in Iraq as a “combat

architect” with the First Marine Expeditionary Force (IMEF) in

Al Anbar Province, western Iraq. He was called to active duty from his

job as state architect for the Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism.

He was tasked with working with local sheiks to determine their construction

needs in Al Fallujah, Ar Ramadi, and later on the western border with

Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia from the Al Asad Forward Operating Base.

What came out of these meetings, he tells us, was a need to design and

construct hospitals, schools, and security projects.

Security has moved to the forefront of operations in Iraq. Al Anbar

province, the largest and most untamed, contains the area of western

desert and the Sunni Triangle. The province borders Syria, Jordan, and

Saudi Arabia along 550 miles of inhospitable terrain. It is within this

area, called “AO Denver,” that the 7th Regimental Combat

Team (RCT-7) of the Marine First Division (1MARDIV) operates. The area

also contains the Euphrates River, and thus the Navy Seabees are there

to provide construction expertise and contracting capability to employ

Iraqi workers and Iraqi contractors to build civil projects such as schools,

hospitals, roads, and bridges. Priorities focus on security infrastructure,

including police stations, Iraqi National Guard compounds, and Iraqi

Border Defenses. Below is a brief summary of four types of projects for

which I was privileged to serve as the First Marine Expeditionary Force

Engineering Group Officer in Charge of Construction (1MEG-OICC) unit.

Security has moved to the forefront of operations in Iraq. Al Anbar

province, the largest and most untamed, contains the area of western

desert and the Sunni Triangle. The province borders Syria, Jordan, and

Saudi Arabia along 550 miles of inhospitable terrain. It is within this

area, called “AO Denver,” that the 7th Regimental Combat

Team (RCT-7) of the Marine First Division (1MARDIV) operates. The area

also contains the Euphrates River, and thus the Navy Seabees are there

to provide construction expertise and contracting capability to employ

Iraqi workers and Iraqi contractors to build civil projects such as schools,

hospitals, roads, and bridges. Priorities focus on security infrastructure,

including police stations, Iraqi National Guard compounds, and Iraqi

Border Defenses. Below is a brief summary of four types of projects for

which I was privileged to serve as the First Marine Expeditionary Force

Engineering Group Officer in Charge of Construction (1MEG-OICC) unit.

Project Type 1: Iraqi Border Police denial forts

When Saddam Hussein’s regime fell, so did the internal security

of the country. Police forces and army units were disbanded. The borders

that had suffered some coalition attacks at the outset of the war were

abandoned, and the small over-watch forts along the remote borders with

Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia were vacated. In this vacuum of power,

foreign fighters and smugglers began to cross the borders, bringing with

them more fighters, equipment, and weapons.

Topping

the 1MEG-OICC’s list of projects when we moved into our

new office at the once-secret Iraqi Air Force Base in western Al Anbar

was establishing and sustaining the once-defunct Border Police Force.

After meetings in late April 2004 with the provincial leadership of the

Border Police, the Marines put forth a strategy to construct new border

denial forts at regular intervals along the most affected parts of the

border with Syria. With input from Iraqi Department of Border Enforcement

Colonel Ali A. Hady, I designed a Beau-Geste style “fort” with

rounded corner towers and a center courtyard surrounded by an array of

rooms, which would act as a fortress security point at known crossing

points to interdict the “rat lines” of smugglers.

Topping

the 1MEG-OICC’s list of projects when we moved into our

new office at the once-secret Iraqi Air Force Base in western Al Anbar

was establishing and sustaining the once-defunct Border Police Force.

After meetings in late April 2004 with the provincial leadership of the

Border Police, the Marines put forth a strategy to construct new border

denial forts at regular intervals along the most affected parts of the

border with Syria. With input from Iraqi Department of Border Enforcement

Colonel Ali A. Hady, I designed a Beau-Geste style “fort” with

rounded corner towers and a center courtyard surrounded by an array of

rooms, which would act as a fortress security point at known crossing

points to interdict the “rat lines” of smugglers.

The forts were designed to be built in very remote locations and occupied at any one time by 28 persons who patrol up and down the border between the forts in vehicles. While the Civil Affairs Group provided clothing, equipment, and training to the enthusiastic volunteers swelling the ranks of the reestablished Iraqi border patrol, it was up to me and the MEG OICC to solicit the design for bids, award contracts, and oversee construction of 32 forts along the 550-mile border.

The forts are approximately 16 miles apart. The first eight were done

as a test near the Euphrates River-crossing town of Husaybah, an anti-coalition

forces stronghold that served as the scene of some of the post-combat

war’s fiercest fighting. The project was delayed by intimidation,

kidnapping, and beheading of several contractors working on coalition

projects the summer of 2004. Roadside bombs (improvised explosive devices,

or IEDs) brought the work to a halt for a while. Still, 24 additional

forts were awarded to three contractors, with 8 forts for each. One contractor,

threatened with death by masked insurgents at his home, quit the job.

During an on-site inspection, one fort had been booby-trapped in an attempt

to destroy it with explosives; another had six artillery shells rigged

to blow it up. During our site visits, we brought along an Explosive

Ordnance Disposal person, who was able to diffuse the explosives and

destroy the shells, saving these two forts from destruction.

The forts are approximately 16 miles apart. The first eight were done

as a test near the Euphrates River-crossing town of Husaybah, an anti-coalition

forces stronghold that served as the scene of some of the post-combat

war’s fiercest fighting. The project was delayed by intimidation,

kidnapping, and beheading of several contractors working on coalition

projects the summer of 2004. Roadside bombs (improvised explosive devices,

or IEDs) brought the work to a halt for a while. Still, 24 additional

forts were awarded to three contractors, with 8 forts for each. One contractor,

threatened with death by masked insurgents at his home, quit the job.

During an on-site inspection, one fort had been booby-trapped in an attempt

to destroy it with explosives; another had six artillery shells rigged

to blow it up. During our site visits, we brought along an Explosive

Ordnance Disposal person, who was able to diffuse the explosives and

destroy the shells, saving these two forts from destruction.

In addition to the danger of explosives, travel on site visits was difficult

at first. On July and August afternoons, it is 140 degrees Fahrenheit

in the shade, and the metal of the vehicle is too hot to touch. The most

reliable means of travel was to hop on a Marine patrol heading up and

down the border in light armor vehicles (LAVs). A patrol can take several

days and nights in the desert. It is a no-frills camping experience where

you sleep on the ground and knock off scorpions all night.

In addition to the danger of explosives, travel on site visits was difficult

at first. On July and August afternoons, it is 140 degrees Fahrenheit

in the shade, and the metal of the vehicle is too hot to touch. The most

reliable means of travel was to hop on a Marine patrol heading up and

down the border in light armor vehicles (LAVs). A patrol can take several

days and nights in the desert. It is a no-frills camping experience where

you sleep on the ground and knock off scorpions all night.

Time-honored construction

A denial fort has just one entry—on the Iraqi side of the border.

The side that faces the other border has no windows so as not to receive

small-arms fire. Construction techniques are time-honored pre-industrial

age. Foundations are built of rock, and then 16-inch-thick, heavy-rock

masonry walls are built on top of the foundation walls. (There are no

slabs-on-grade or wood stud walls; in fact, there is very little wood

used at all.) Once the walls are built up to 10 feet tall, workers install

a wooden shoring system and pour a concrete roof with steel reinforcing

bars. When it is dry, they remove the shoring and use soil to raise the

floor up to about 6 inches below the finished floor level and pour a

concrete base. Hand-set floor tiles go into a three-inch coat of setting

mortar.

Workers rough-finish the walls with stucco, then trowel on a gypsum-plaster

finish coat. To complete the work, they cut the glass and put in the

steel window frames, paint the walls, and install electrical and plumbing

fixtures. Toilets are Eastern-style trench toilets. It is normal to see

the toilet combined with a shower unit with the toilet acting as a floor

drain.

Workers rough-finish the walls with stucco, then trowel on a gypsum-plaster

finish coat. To complete the work, they cut the glass and put in the

steel window frames, paint the walls, and install electrical and plumbing

fixtures. Toilets are Eastern-style trench toilets. It is normal to see

the toilet combined with a shower unit with the toilet acting as a floor

drain.

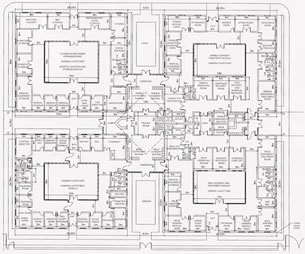

Project Type 2: Ar Rutbah Hospital

The 25,000-person town of Ar Rutbah, which also served as the center

for regional health care for all of rural western Al Anbar (an area

the size of Utah), lost its hospital to coalition bombing in the 2003

Operation Iraqi Freedom. For our second major project, our design team

devised, developed, drew, and is now overseeing construction of a modern

25,000-square-foot, 100-bed hospital on the same site as the destroyed

hospital. I proposed and sketched up a plan using centralized communicating

public space and four modular wings to reduce travel time from the

entry lobby and all other functions of the hospital.

To allow caregivers to observe and maintain visual control over as many

patient treatment and recovery rooms as possible, the design incorporates

a central open-air courtyard with glass-enclosed corridors that allow

through-views. All four wings are quickly accessible by the center public

waiting space, which also offers prayer space for patients and visitors

alike.

To allow caregivers to observe and maintain visual control over as many

patient treatment and recovery rooms as possible, the design incorporates

a central open-air courtyard with glass-enclosed corridors that allow

through-views. All four wings are quickly accessible by the center public

waiting space, which also offers prayer space for patients and visitors

alike.

We tried a new concept on this project to get complete community buy-in of the project. We wrote into the solicitation for bids that the contractor must provide letters of approval and reference from the Ar Rutbah City Council, mayor, police chief, Iraqi National Guard commander, the local imams (clerics), and sheiks (the local tribal leaders). These reference letters were heavily weighted as a technical evaluation criterion. They weeded out a lot of out-of-town contractors, which, if selected, may have added to the volatile nature of the city. Twenty-five contractors submitted bids for the project, and the selected contractor is from the town and has close knowledge of the community and business relationships. The project broke ground in September of last year; I was able to fly in via helicopter for the ceremony.

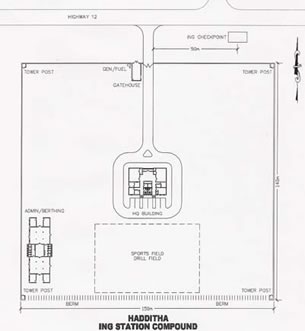

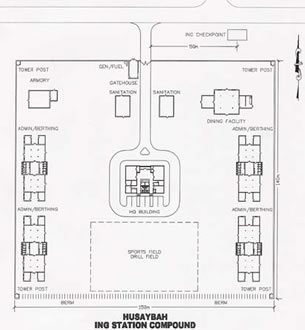

Project Type 3: Iraqi National Guard (ING) Compounds

Project Type 3: Iraqi National Guard (ING) Compounds

The third program I managed entailed construction of 8 ING compounds

for the Iraqi Ministry of Defense in cities along the Euphrates River

valley. These compounds provide security for the Iraqis in the areas

outside of cities and towns. Defensive compounds have been designed

using a modular concept of a menu of buildings task-oriented and tailored

to the needs of the area.

Each site gets a basic compound of a perimeter wall, entry control gate, and headquarters building. As the unit is enlarged or requires more facilities, buildings are added to the compound, accommodating up to 250 people before the compound needs to be enlarged. As of this writing, eight sites have been awarded for construction in two phases of a three-phase master plan. However, none of the eight sites has yet begun construction due to insurgent targeting in these areas.

Project

Type 4: Iraqi Border Police Training Academy

Project

Type 4: Iraqi Border Police Training Academy

The fourth program I created and managed during my tour in Iraq is the

design and construction of a modular campus plan for the training academy

used by the border police and the national police force. Situated next

to an ancient oasis just west of Al Asad Air Base, the plan includes

classrooms; conference spaces; living quarters; administrative areas;

dining hall, stores, and warehousing for weapons, uniforms, and training

gear; and a prayer space. We broke ground on the project last October

and in November were informed that we were to enlarge the academy to

four times the size! I am preparing the designs as of this writing.

The site includes an old village that Saddam Hussein’s regime relocated during the construction of the air base in 1985. The buildings exhibit some ancient construction methods and have been preserved for future study of their cultural significance. A couple of rundown buildings and an old elementary school have been incorporated into the design as training buildings.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

|

||