05/2005

by Heather Livingston

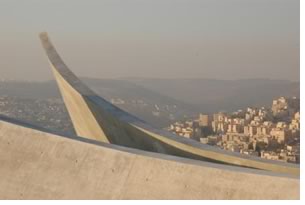

Dedicated on March 15, Moshe Safdie’s new Holocaust History Museum

replaces a generic and outdated “black box” museum with a

striking 180-meter-long prism-like triangular building that cuts through

Jerusalem’s Mountain of Remembrance. Cantilevered into the air

at both ends, one side dramatically erupts into a breathtaking terrace

view of forest, mountain, and the city below. A glass skylight spans

the length of the building, permitting glimpses of daylight down into

the central corridor.

Dedicated on March 15, Moshe Safdie’s new Holocaust History Museum

replaces a generic and outdated “black box” museum with a

striking 180-meter-long prism-like triangular building that cuts through

Jerusalem’s Mountain of Remembrance. Cantilevered into the air

at both ends, one side dramatically erupts into a breathtaking terrace

view of forest, mountain, and the city below. A glass skylight spans

the length of the building, permitting glimpses of daylight down into

the central corridor.

There’s a lot of personal connectedness for Safdie with Yad Vashem, Israeli’s national authority for the Remembrance of the Martyrs and Heroes of the Holocaust and their Mountain of Remembrance site on the western outskirts of the city. In 1976, he designed Yad Vashem’s Children’s Memorial, a tribute to more than a half million Jewish children who died during the Holocaust. In the early ’90s, he was the architect for the Cattle-Car Memorial to the Deportees, which memorializes “the millions of Jews herded onto cattle-cars and transported from all over Europe to the extermination camps.”

A pastoral site

A pastoral site

Of his inspiration for the Holocaust History Memorial, Safdie says, “My

first thought in terms of the design was that this was such a pastoral site

that putting a great big building of a new museum on top of the mountain would

overwhelm it and create a building that was inappropriate. So, very early in

the process, I had the sense of somehow going into the mountain. I guess the

big breakthrough was the idea that you come into the mountain from one side

and break through on the other. It literally penetrates the mountain from one

side to the other.”

Another inspiration, Safdie says, was a pictures he had seen of a stone quarry in Spain that had been converted into a kind of park of enormous underground chambers with shafts going up for light, which was just the result of quarrying stone. “I had the idea that the galleries where the story of the Holocaust would be told would be almost like archaeological remnants or excavations in the natural rock in scale and detail,” he says.

Constructed entirely of reinforced concrete, the new museum posed some

formidable technical challenges, Safdie notes.“Yad Vashem is a

public body, so it is constrained by all of the bidding procedures of

a government organization—competitive bidding, etc. You can’t

just negotiate a deal. With those constraints, it’s remarkable

to be able to get a group of contractors and subcontractors to produce

this kind of concrete work,” he says. “There’s not

a single expansion joint in the building. It’s totally post-tensioned.

No cladding or waterproofing or thermal insulation, and it’s continuously

cast-in-place concrete from end to end. I don’t think you’ve

ever seen concrete work like that anywhere in the world.”

Constructed entirely of reinforced concrete, the new museum posed some

formidable technical challenges, Safdie notes.“Yad Vashem is a

public body, so it is constrained by all of the bidding procedures of

a government organization—competitive bidding, etc. You can’t

just negotiate a deal. With those constraints, it’s remarkable

to be able to get a group of contractors and subcontractors to produce

this kind of concrete work,” he says. “There’s not

a single expansion joint in the building. It’s totally post-tensioned.

No cladding or waterproofing or thermal insulation, and it’s continuously

cast-in-place concrete from end to end. I don’t think you’ve

ever seen concrete work like that anywhere in the world.”

Personal and humane

Personal and humane

In the works for 10 years, the Holocaust History Museum presents the experience

of the Holocaust from the Jewish perspective. Unlike the former incarnation,

the new museum focuses on the individual histories and narratives of the

Holocaust, thus revealing and remembering the devastation in a very personal,

humane way. The building is organized around 10 galleries that zigzag across

the central axis of the museum to take visitors chronologically from “The

Jewish World before the Holocaust, 1900–1933” to “From

Liberation to DP Camps and Rehabilitation.” Says Safdie, “You’re

conscious of where you are all the time and of other people as you see the

exhibits. Though you’ve actually got to go on the zigzag path from

chapter to chapter, you still are constantly oriented to your final destination.”

The galleries themselves are shrouded in darkness to keep the emphasis on the exhibit, respect those who were lost, and ponder the significance of the events with minimal environmental distraction. Safdie describes the rooms as neutral with tall, black ceilings and only one light shaft penetrating. “The galleries are all 8 meters [app. 26 feet] high, and the exhibits tend to fill up the first 4 meters, so there’s a lot of flowing space above.” Each gallery has an independent 2 x 2-meter [6.5 x 6.5-feet] skylight that provides illumination for the exhibit. The central prism skylight reinforces the darkness of the space by giving the visitor the illusion of descending far into the mountain. The exhibits portray the personal stories of Jews, before and during the Holocaust, through a combination of photographs, objects and artifacts, testimonies, and computer displays.

Following

the exhibit galleries is the Hall of Names, an archive for the “Pages

of Testimony,” which document the lives and personal

histories of victims of the Holocaust. There visitors can search a database

or add information on victims in the Pages of Testimony. The Hall of

Names is composed of “two cones, one going into the rock and one

going upwards.” The upper cone soars 35 feet into the air and

displays approximately 600 photographs of Holocaust victims and fragments

of Pages of Testimony. The lower cone descends into a “well-like

cone excavated into the natural underground rock” and filled with

water. The water reflects the photographs above and serves to commemorate

those victims still unknown.

Following

the exhibit galleries is the Hall of Names, an archive for the “Pages

of Testimony,” which document the lives and personal

histories of victims of the Holocaust. There visitors can search a database

or add information on victims in the Pages of Testimony. The Hall of

Names is composed of “two cones, one going into the rock and one

going upwards.” The upper cone soars 35 feet into the air and

displays approximately 600 photographs of Holocaust victims and fragments

of Pages of Testimony. The lower cone descends into a “well-like

cone excavated into the natural underground rock” and filled with

water. The water reflects the photographs above and serves to commemorate

those victims still unknown.

A sense of renewal

A sense of renewal

At the terminus of the Holocaust History Museum is the observation terrace,

which peels open to reveal the city below. “I think the two most moving

parts architecturally are the Hall of Names and the terrace at the end where

it sort of explodes outward and you’re looking at the view,” notes

Safdie. “That’s certainly the moment where people’s emotions

have been most extreme. Coming out of the depth of the mountain and seeing

the horrible exhibits, the sense of renewal that you get is very powerful.”

When describing public reaction to the Yad Vashem Holocaust History Museum, Safdie says that “people have been very, very moved. This building has evoked more emotional responses than any other building I’ve ever done. It’s been extraordinary.” Most personally significant and moving for Safdie was “walking hand-in-hand on the opening day with [author of over 30 books and Nobel Peace Prize Laureate] Elie Wiesel from end to end and seeing it through his eyes for the first time.”

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

To learn

more, visit the Yad Vashem Web site. Visit Moshe Safdie and Associates online.

|

||