04/2005

by Jonathan Moore

“No one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place and the kindness of these people, I owe everything.” So stated Abraham Lincoln on February 11, 1861, as he boarded a train for Washington, D.C., and his appointment with history. The city he bade an affectionate farewell was Springfield, Ill., a capital city nestled on the edge of the Western frontier and Lincoln’s home for almost a quarter century. The president-elect humbly acknowledged the support and affection of his neighbors, presciently reminding them of the challenging and perilous journey that lay ahead.

Two months after Lincoln’s departure, the nation plunged into civil war. Four years later Lincoln’s remains returned to Springfield as our nation’s first martyred president. Seven-score years later, Lincoln remains enshrined as Springfield’s most cherished son. Here in the fertile plains of central Illinois, Lincoln honed his leadership skills; first as a state lawmaker and successful lawyer, then as a U.S. congressman, senatorial candidate, and, ultimately, president. Yet in this “Land of Lincoln,” site of his final resting place, no official library or museum existed for scholars and the general public.

Library and museum

Library and museum

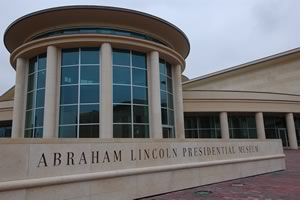

That fact itself became history on April 19, 2005, with official dedication

ceremonies for the new Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

(ALPLM) capping years of effort by civic volunteers, government officials,

and Lincoln scholars. Gyo Obata, FAIA, founding partner of Hellmuth,

Obata + Kassabaum Inc. (HOK) and his design team created a two-building,

200,000-square-foot, $150 million facility housing authentic documents

of the famed Lincoln Collection, and a museum featuring virtual reality

exhibits showcasing the remarkable life of our 16th president.

Working with Illinois’ Capital Planning Development Board and the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency (IHPA), Obata teamed with Bob Rogers, chair and founder of BRC Imaginative Arts of Burbank, Calif., to design a pioneering “experience museum” where 21st-century technology brings 19th-century history to life. Four stories in height, ALPLM anchors the corner of downtown Springfield’s North Sixth and Jefferson Streets.

Serving as ALPLM’s principal designer, Obata studied conceptual contexts of Springfield’s adjacent historic structures, seeking to avoid more institutional designs. Selecting a contemporary style he termed “civic monumentality,” Obata fused classical concepts with modern free-flowing curvature elements. This includes the use of entryway rotundas, flat roofs with eave overhangs, and semi-circular columns lining the principal facade framed with large tinted windows.

For the envelope of both buildings, Obata selected a warm beige limestone, contrasting with the darker brown limestone of the Old State Capitol nearby. In conjunction with Fred Goebel, AIA, an HOK colleague and ALPLM’s project manager, Obata commenced an exhaustive search before discovering his choice of stone half a world away in Egypt. Composed of sturdy light material roughly an inch thick, this Egyptian stone was cheaper to quarry and easier to transport than similar stone in the States. Obata and Goebel contracted with Italian artisans, who shaped the stone into block patterns before shipment to Illinois, thereby reducing total installation costs.

“I sought similar unique styles for the library and museum,” Obata says. “Contemporary architecture takes shape from many different forms, which provides ample latitude for achieving a structure’s purpose. Honoring Lincoln and his life’s work, I designed the library and museum as one entity serving two separate but complementary functions.” Obata’s reverence for Lincoln gives both buildings a dignified Modern look, making it apparent that architect and subject were a perfect match.

Same outside, different within

Same outside, different within

Virtually identical in exterior appearance, the two buildings have different

interiors using different atrium configurations. The $25 million library

contains authentic collections of state historical and Lincoln papers,

along with photo and document conservation labs, audio/visual viewing

rooms, and multi-purpose conference areas for meetings and seminars.

Until the library opened in October 2004, reams of historical documents, books, and photographs were stored in the Old State Capitol’s basement. Becoming space-constrained, with cramped quarters and windowless rooms, librarians and curators craved additional shelving capacity as well as exposure to environs above terra firma. A master of blending natural elements within harmonious fields of natural light, Obata was more than happy to oblige. The new 100,000-square-foot library offers a testament to handsome, spatial elegance. Beyond the main entryway, three levels surround a central rectangular atrium with a gleaming wood floor. Soft lighting meshes deftly with natural sunlight, casting a brownish-golden glow from maple wood paneled walls.

“I am inspired by creating designs that enhance the richness of human activities,” he adds. “Listening to IHPA’s needs, we designed a library providing scholarship with resources for a variety of historical presentations. This building achieves aesthetic, cultural, and educational dimensions honoring America’s greatest president, as well as the rich history of the Midwest.” Six miles of compact book shelving more than doubles capacity from the state library’s previous quarters. There is also 66 percent more manuscript storage, 4,728 cubic feet of audio/visual cabinetry (quadrupling the former A/V unit), and 22,000 square feet devoted to stack storage.

Most of the Lincoln Collection now resides in a secure, climate-controlled lower-level area. Archivists and curators there keep watch over such priceless artifacts as signed copies of the Emancipation Proclamation, the 13th Amendment (legally abolishing slavery), and the Gettysburg Address. The collection also includes six original portraits of the president and Mrs. Lincoln, and the only known photograph of Lincoln lying in state. Twelve million additional documents chronicle Illinois’ 187-year history.

Back to the 19th century

Back to the 19th century

Across from the library, 44,000 square feet of virtual-reality exhibits

and theater attractions beckon in the new presidential museum. Stepping

into the rotunda-shaped atrium, visitors are transported into 19th

century America. Obata’s mastery of open space and light is apparent

again in this rotunda, replete with windows almost touching the ceiling

and a radiant sundial etched on the Grecian marble floor. Breaking

tradition from sepia-tone daguerreotypes and static displays found

in other museums covering the era, this central location reveals a

host of innovative options for visitors to explore.

Projecting from corrugated wood-paneled walls are two contrasting scenes from Lincoln’s life. Visitors can enter a rustic, life-sized log cabin in the dense woods of Southern Indiana or pass through the elegant colonnaded South Portico of the White House. Two movie theaters feature immersive presentations of Lincoln’s impact on history—one using suspended digital images and a live-performance narration detailing the wondrous discoveries of Lincoln archives. Flanking the rotunda is The Illinois Gallery, housing temporary exhibits, and “Mrs. Lincoln’s Attic,” an interactive playroom for young children and their families. Rounding out the first floor is a restaurant and gift shop, the latter located off the main entrance.

Departing from standard glass-enclosed displays, HOK and BRC designed intricate corridors of carpeted walkways and display areas drawing the visitor into Lincoln’s world. Designed by BRC technicians, this “immersive experience” provides a you-are-there feeling—from the humble quarters of Lincoln’s early days to various rooms in the Executive Mansion, where epochal decisions changed the course of history. Completing the 137,000-square-foot facility at the upper levels are administrative offices, building and exhibit technician rooms, and archival storage.

Catching the spirit

Catching the spirit

“When you live in the Midwest, it’s hard not to be inspired

with the spirit of Abe Lincoln,” says Obata. “Over the years,

I have come to know and admire this man for his strong sense of purpose

and the incredible challenges he met and endured.” In designing ALPLM’s

reflective open-air environment, Obata strove to attract casual visitors

who might otherwise overlook the historical treasures describing Lincoln’s

story.

Like Lincoln’s circuitous road from humble beginnings, ALPLM experienced its own twists and turns before becoming reality. As a trustee in 1981 with the Illinois State Historical Society, Julie Cellini was reviewing Lincoln documents with the state’s curator. Suddenly the curator handed her an original signed copy of the Gettysburg address. Holding the 272 words was an epiphany for the Illinois native. “Here in President Lincoln’s hometown, I realized these priceless materials were housed in areas largely inaccessible to the public,” said Cellini. “It dawned on me that a first-rate library and museum telling his incredible story was urgently needed.” Cellini’s idea ignited a 20-year crusade. Joining forces with the state’s Capitol Planning Development Board, three Illinois governors, the state’s congressional delegation, noted Lincoln scholars, civic leaders, and countless volunteers, Cellini and company tirelessly promoted ALPLM before federal and state officials.

Cellini says the unique partnership of architects, exhibit technicians, and historians has proved invaluable. “Right from the start, we sought a new approach to learning about Lincoln. Hopefully these buildings will rekindle an interest for exploring his fascinating life—beyond standard information found in textbooks—so visitors come away with a renewed appreciation for the man who saved our nation.”

Immersive environment

Immersive environment

Bob Roger’s museum exhibits capture visitors’ interest from

the moment they enter. “In this age of increased visual orientation,

it is important for people to become emotionally attracted to Lincoln

early in the process,” Rogers adds. “This museum doesn’t

just teach history, it places you in an immersive environment of sight,

sound, and visual sensation. Gyo Obata and his team designed a structure

from the inside out that helped achieve this objective.” Rogers

explains that comparing today’s political partisanship with the

intensity of rhetoric in Lincoln’s time makes today’s discourse

seem almost tame. “I want visitors to pick up on that,” he

says. Before exiting the exhibit area, a final surreal scene brings Lincoln

back home to Springfield as his casket lies in state in Representatives

Hall of the Old State Capitol.

Mixing 19th-century scenes with a contemporary flair defines the success of the ALPLM complex. Visual space and innovative technologies flourish in an aesthetic educational environment. Generous use of refractive light, open space, acoustics, and accessibility provide enjoyment for scholars and tourists alike. “As a collaborative model, this project surpassed everyone’s expectations,” Goebel says. “Good communication between our firm, IHPA, and the exhibitors resulted in a facility of national caliber that goes a long way toward interpreting Lincoln’s legacy.”

As with any new building for the public, the museum will likely have its share of detractors. After all, this venture introduces new methods for historical presentation of a president much revered, but at times still a topic of heated discussion. “When telling a major figure’s life story, intellectual standards can coexist with visual exhibits appealing to a wide-ranging audience,” says noted author and historian Richard Norton Smith, ALPLM’s executive director.

Having directed other presidential libraries, Smith believes design and content can complement each other, adding that many of today’s museums are trending towards contemporary classroom concepts. “This museum offers visitors of all ages a chance to discover timeless themes that affected Lincoln in his day,” Smith adds. “We want this to be the beginning of a journey of discovery into Lincoln’s life and times. This in turn could spark further reflection for history’s sense of purpose, demonstrating how past events often influence the present.”

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

|

Jonathan Moore is a public affairs consultant in Alexandria, Va. with Smith & Harroff, Inc., and formerly with AIA Government Affairs.

|

||