05/2005

In celebration of Earth Day 2005, April 22, the AIA and its Committee on the Environment selected nine examples—eight awards and one honorable mention for a planning project—of green design that protects and enhances the environment. The selected projects address significant environmental challenges with designs that integrate architecture, technology, and natural systems. The projects and their architects will be honored in May at the AIA National Convention in Las Vegas.

The seventh annual AIA/COTE initiative was developed in partnership with the U.S. Department of Energy and Environmental Building News magazine. The jurors—Robert Berkebile, FAIA; Daniel H. Nall, FAIA; Susan A. Maxman, FAIA; Henry I. Siegel, FAIA; and Deborah Snoonian, PE—considered 10 metrics for each project: process, finance, land use, site/water, energy, materials, indoor environment, images, ratings/awards, and lessons learned.

The 2005 Top Green Projects are:

Austin

Resource Center for the Homeless (ARCH), Austin, Tex. by LZT Architects

Austin

Resource Center for the Homeless (ARCH), Austin, Tex. by LZT Architects

This 27,000-square-foot, new building serves as a meeting place and support

center to help people transition out of homelessness. ARCH consists of

a large common-use day room, shower and locker rooms, laundry facilities,

computer room, art studio, and offices for various community support

agencies. Located on the third floor in a pavilion-like structure on

the roof is the 100-bed overnight shelter. Sited on a former brownfield,

ARCH employs a 13,000-gallon rainwater collection system to supplement

the building’s nonpotable water supply. A passive-solar hot-water system

preheats water for the showers. Electrical usage is supplemented by a

photovoltaic array. The “stack-cast tilt-frame” structural

system, developed specifically for this project, reduces the amount of

finished materials and formwork used and increases the quality of the

exposed concrete finish. The strong connection between interior and exterior,

created through the numerous interpenetrating volumes, allows natural

light and views into more than 90 percent of the work spaces.

Photo © Thomas McConnell Photography.

The

Barn at Fallingwater, Mill Run, Pa., by Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, Architects

The

Barn at Fallingwater, Mill Run, Pa., by Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, Architects

The Barn at Fallingwater offers an adaptive reuse of a 19th-century heavy-timber

bank barn and its 20th-century addition, framed in dimension lumber.

It serves as an interpretive portal for the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy’s

5,000-acre Bear Run nature reserve, immediately adjacent to Frank Lloyd

Wright’s Fallingwater. The grand upper level of the original bank barn

is used as a seasonal area for exhibits, lectures, and other social functions.

The one-story 20th-century addition now houses a multipurpose exhibit,

conference, and distance-learning area. The existing, glazed block walls,

glass block windows, and site-built roof trusses are exposed. Salvaged

fir, new sunflower-seed composite panels, and sound-absorbing straw panels

complement the palette of original materials while underscoring the structure’s

connection to farming. A zero-discharge wastewater reclamation system,

graywater flushing, and low-flow fixtures reduce potable water use. A

ground-source heat-pump system, daylighting, and electric light sensors

minimize energy use.

Photo © Mike Gwin.

Eastern

Sierra House, Gardinerville, Nev., by Arkin Tilt Architects

Eastern

Sierra House, Gardinerville, Nev., by Arkin Tilt Architects

The architects carefully designed this new, 3,450-square-foot sustainable

demonstration home to take advantage of the rugged beauty of its site

on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, overlooking the

Carson Valley. Working with the slope, orientation, and dramatic views,

the house centers on a courtyard oasis shaded by a photovoltaic array.

While the garage and guest wing to the west blend into the landscape

via sod roofs, the main form juts out like a boulder, its south-facing

roof (oriented for photovoltaic collection) peeling up at the corner

for passive solar gain and a dramatic view of a snow-capped peak. Using

a variety of natural, efficient, and durable materials—primarily

straw bale with an earthen finish (using site soils), metal roofing,

and slatted cement-board siding—the finishes harmonize with the

landscape. The house is virtually energy independent: Careful shading,

high insulation values, and thermal mass keep the structures from over-heating

in the summer, aided by the flushing of cool night air. In the winter,

solar hot water panels located at the edge of the terrace feed a deep,

sand-bed hydronic heating system and provide domestic hot water.

Photo© Edward Caldwell Photography.

Leslie

Shao-Ming Sun Field Station, Woodside, Calif., by Rob Wellington Quigley,

Architects

Leslie

Shao-Ming Sun Field Station, Woodside, Calif., by Rob Wellington Quigley,

Architects

The Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve is a 1,200-acre protected area in

the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains, near Stanford University.

As Stanford’s first green building, this 13,000-square-foot field

station was designed to provide a natural laboratory for researchers,

educational experiences for students and visitors, and refuge for native

plants and animals. Site selection considered solar access and impact

on natural habitats and archeological resources, and construction site

management included fencing to prevent work under the drip line of mature

oaks. The building itself includes a 22-kilowatt, grid-connected photovoltaic

system and a sophisticated energy monitoring system. Passive cooling

and solar heating systems combine with good insulation and extensive

daylighting to minimize energy use. Waterfree urinals, dual-flush toilets,

tankless water heaters, and native landscaping reduce water use, and

rainwater collected from the roof is reused. The architect used salvaged,

reused, recycled, and low-VOC materials when possible. Salvaged materials

were used for siding, brick paving, casework, furniture, and bathroom

partitions.

Photo© Brighton Knowing.

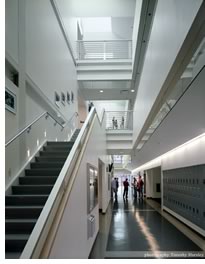

M.

E. Rinker Sr. Hall, Gainesville, Fla., by Croxton Collaborative Architects

+ Gould Evans Associates, a Joint Venture

M.

E. Rinker Sr. Hall, Gainesville, Fla., by Croxton Collaborative Architects

+ Gould Evans Associates, a Joint Venture

Rinker Hall is a new, three-story, 47,000-square-foot higher-education

leadership facility within the University of Florida’s College of Design

and Construction. The building serves the 450 students of the school’s

Building Construction program through a mix of classrooms, teaching labs,

construction labs, faculty and administrative offices, and student facilities.

In 2004, it achieved a LEED™ Gold rating. The architects oriented

the building on a pure north-south axis and thus capture low-angle light

for daylighting. Egress paths from all classrooms at all levels are continuously

daylighted, allowing for emergency exit during a daytime power failure.

Materials were considered with three goals: first, to minimize built

solutions; second, to minimize the materiality of those solutions; and,

third, to facilitate disassembly through materials selection, assembly,

and detailing. The architects also were able to take advantage of the

building’s edges and make the assembly room on the north and the

construction shop on the east indoor/outdoor spaces.

Photo © Timothy Hursley.

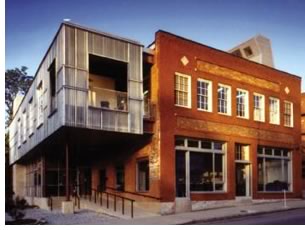

Pittsburgh

Glass Center, Pittsburgh, by Davis Gardner Gannon Pope Architecture/Bruce

Lindsey

Pittsburgh

Glass Center, Pittsburgh, by Davis Gardner Gannon Pope Architecture/Bruce

Lindsey

This two-story, 17,600-square-foot building is a reuse and neighborhood

revitalization project whose design process included meetings and charrettes

with all project stakeholders, including the general public. The building

uses daylighting and control of the quality of the light, as well as

extensive natural ventilation in an environment where air-conditioning

is prohibitively expensive. Heat from the glassmaking equipment is recovered.

Thermal mass inside the building moderates temperature swings. A reflective

and emissive roof system reduces both internal heat loads and the building’s

contribution to the urban heat-island effect. The parking lot uses pervious

limestone and is landscaped with indigenous plants; it doubles as an

event courtyard and reduces heat build-up in summer months. The architects

also incorporated landscaping and surface treatments to shade the parking

lot and the building.

Photo © Ed Massery.

Sarah

Lawrence Heimbold Visual Arts Center, Bronxville, N.Y., by Polshek

Partnership, Architects

Sarah

Lawrence Heimbold Visual Arts Center, Bronxville, N.Y., by Polshek

Partnership, Architects

This 60,000-square-foot center, in addition to establishing a new place

for the arts on campus, plays a leadership role in creating a building

that is rooted in the fundamental principles of sustainable design. To

reduce the impact to its wooded site and blur the distinction between

exterior and interior, the new building is integrated into the topography

of the existing hilltop. One-third of it is fully underground. In selecting

the building’s primary materials—fieldstone, cedar, channel glass,

and zinc—the architect found inspiration in the campus’s rich landscape

and its historic architecture. Quarrying the stone near the site continued

the college’s history of using local fieldstone in the construction of

its buildings and furthered the goal of obtaining a LEED™ rating

for the building. In addition, more than 60 percent of the project’s

wood materials are certified as sustainably harvested by the Forest Stewardship

Council. Native and drought-tolerant plants and low-flow fixtures reduce

water use while indoor environmental quality is improved through the

use of daylighting and operable windows.

Photo © Richard Barnes/Polshek Partnership.

Seminar

II, The Evergreen State College, Olympia, Wash., by Mahlum Architects

Seminar

II, The Evergreen State College, Olympia, Wash., by Mahlum Architects

Design implementation for this 168,000-square-foot academic facility

reflects the Evergreen State College’s commitment to rigorous interdisciplinary

teaching and environmental advocacy. To create smaller learning communities

based on the academic program, the architect designed the project as

five semi-independent buildings (academic clusters). Each cluster supports

four interdisciplinary academic programs and is composed of faculty offices,

student “homerooms,” seminar rooms, breakout spaces, a workshop,

and a lecture hall. A central open volume allows daylighting, natural

stack ventilation, and visual connections among the academic programs.

A system of open walkways, stairs, and bridges tie together the levels,

and outdoor classrooms extend from each lower level into this landscape.

To reduce the impact of the project on Thornton Creek and its native

salmon, a vegetated roof covering half of the footprint was installed.

The final design achieved 80 percent natural ventilation with mechanical

cooling in the two large lecture and meeting rooms on the ground floor

of each cluster.

Photo © Lara Swimmer.

And, though not a building, the jury applauded this plan’s effort and found it worthy of an award.

Lloyd

Crossing Sustainable Urban Design Plan, Portland, Ore., by Mithun Architects

Lloyd

Crossing Sustainable Urban Design Plan, Portland, Ore., by Mithun Architects

The Lloyd Crossing Sustainable Urban Design plan integrates multiple

sustainable strategies for energy, water, and habitat to transform and

create a new identity for a 35-block, inner-city, commercial Portland

neighborhood. The plan creates a new analytical, design, and economic

framework for adding 8 million square feet of development over 45 years

while dramatically improving the district’s environmental performance.

Pre-development metrics were created as an environmental goal to strive

for matching the performance of the ‘pre-development’ coniferous

forest in new development strategies, while increasing density fivefold.

Tree cover, solar utilization, carbon balance, and water use were among

the factors measured against the predevelopment metrics. The architects

created unique urban streetscapes and open-space patterns to integrate

and celebrate water, energy, and habitat strategies. A new economic entity

called the Resource Management Association was designed to harness public

and private resources to implement the sustainable strategies over 45

years. All of these elements are combined in the Catalyst Project, a

four-block, mixed-use project serving as the testing ground for the plan’s

key elements.

Rendering courtesy of the architect.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

For more

information on these projects, visit the AIA Green Projects Web

site. The AIA COTE would also like to recognize the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Energy Star Program, which became a partner in the Top Green Projects initiative in 2003.

|

||