04/2005

Kenzo

Tange, Hon. FAIA, the 1966 AIA Gold Medalist and 1987 Pritzker Prize

recipient, died in his Tokyo home March 22. He was 91.

Kenzo

Tange, Hon. FAIA, the 1966 AIA Gold Medalist and 1987 Pritzker Prize

recipient, died in his Tokyo home March 22. He was 91.

At the forefront of transforming Tokyo into the megalopolis it is today, Tange embraced the International Style from the outset while blending those industrial precepts with the forms and traditions of his native Japan. Tange first aspired to pursue architecture when, as a teenager, he saw Le Corbusier’s rejected design for the League of Nations, he would often tell interviewers. Following that dream, in the late 1930s he worked in the offices of Kunio Maekawa, who had studied under Corbusier.

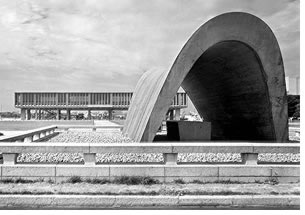

In 1949, Tange garnered international attention when he won the competition to design the Hiroshima Peace Center. His Modern design solution, a narrow rough-concrete and glass pavilion on high stilts, showed obvious influence from Le Corbusier, as did much of Tange’s early work. “This is not to say that Tange copied Le Corbusier,” wrote Wolf Von Eckardt in 1966, “but he was one of the first to adopt, as architects say, Le Corbusier’s ‘vocabulary.’”

The catalyst of tradition

The catalyst of tradition

Tange adapted as much as adopted. For example, the centerpiece of his

Hiroshima pavilion is a massive arched shell abstractly referencing

the funereal houses for Haniwa statues that honor ancient Japanese

nobility. Another early work, completed in 1958, was the Kagawa Prefectural

Office, which emulated in concrete the heavy, highly articulated, and

seismically resistant post-and-beam structures of traditional Japanese

temples.

Tange’s focus was most definitely on the future, though, as he wrote prolifically on a master plan for Tokyo and the definition of Japanese architecture. “Tradition must be like a catalyst that disappears once its task is done,” Tange commented around the same time he completed his doctoral dissertation in 1959, “The Structure of Tokyo City.” In the following few years, he designed the Tokyo City Hall; Sogetsu Art Center, Tokyo; Dentsu Office Buiding, Osaka; Rikkyo University Library, Tokyo; Shizuoka Convention Hall; Shimizu City Hall; Kurashiki City Hall; Housing Project, Takamatsu; and the building many consider his best work of all, the main covered stadium for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

By the time Tange received the AIA Gold Medal in 1966 at age 52, he

already had more major public works to his credit (35) than Frank Lloyd

Wright had completed in his incredibly prolific lifetime (22).

By the time Tange received the AIA Gold Medal in 1966 at age 52, he

already had more major public works to his credit (35) than Frank Lloyd

Wright had completed in his incredibly prolific lifetime (22).

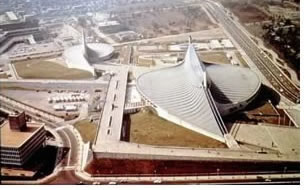

Tange captured the world’s attention again in 1970 as the principal designer for the Osaka Expo 70. By the 1980s, his office had reached 130 architects, among whom were such preeminent designers in their own right as Fumihiko Maki and Arata Isozaki. He was ever the optimist (“I have great facility for forgetting bad news,” he once told Reader’s Digest) and felt his chief obligation as an architect and planner was to create order. “We must anticipate people’s needs,” he said.

The two projects Tange designed in the U.S. are a 1974 addition to the Minneapolis Art Museum and the 1990 AMA Building in Chicago.

Looking to the future

Looking to the future

In 1987, when honored with the Pritzker Prize and its $100,000 stipend,

Tange was working on the western Shinjuku development that includes

the new Tokyo City Hall, which replaced the much-more-modest Modernist

building from three decades before.

“I see no need to preserve this kind of building,” he was quoted in the Washington Post as saying of his first Tokyo City Hall. “Tokyo has experienced very big growth since then, so the building is quite out of date.”

Indeed, it was Tange himself who envisioned Tokyo’s astonishing

growth in the last quarter of the 20th century from his concept of urban

cores he and Maekawa took to the 8th

Congres Internationaux d’Architecture

Moderne in 1951 to Tange’s 1960 Tokyo Plan, which called for extending

the city around and into Tokyo Bay—a plan to which the city continues

to adhere.

Indeed, it was Tange himself who envisioned Tokyo’s astonishing

growth in the last quarter of the 20th century from his concept of urban

cores he and Maekawa took to the 8th

Congres Internationaux d’Architecture

Moderne in 1951 to Tange’s 1960 Tokyo Plan, which called for extending

the city around and into Tokyo Bay—a plan to which the city continues

to adhere.

And, as the city that best expressed Tange’s vision grew and developed, so did his approach to design and its purpose. He expressed his vision of the future of architectural style in his Pritzker acceptance speech (at a time he was moving in Post-Modern directions):

“I believe the development of a new architectural style will result

from further study and work on the three elements that I have discussed:

human, emotional, and sensual elements; technologically intelligent elements;

and social-communicational structure of the space.

“I believe the development of a new architectural style will result

from further study and work on the three elements that I have discussed:

human, emotional, and sensual elements; technologically intelligent elements;

and social-communicational structure of the space.

“In my opinion, further consideration of those views will help us find a way out of the current impasse, and reveal to us the kinds of buildings and cities required by the informational society. We must attempt to discover a new style suitable for our time to express a system of consistent aesthetic elements from the three that I have mentioned, if we are to overcome the eclecticism of the present transitional architectural expressions.”

Funeral services for Tange were held March 25 in the 1964 masterpiece some consider his answer to Corbu’s Notre Dame du Haut at Ronchamps: Saint Mary’s Cathedral in Tokyo.

Copyright 2004 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

Photo of Hiroshima Peace Center copyright Ezra Stoller ESTO. All others courtesy of Kenzo Tange Associates

|

||