04/2005

Every other year, representatives from the AIA and the American Library Association gather to celebrate the finest examples of library design by architects licensed in the U.S. The 2005 AIA/ALA Library Building Awards honor eight disparate projects, ranging in size from an architecture school library to the central facility for a major city. All share successful resolution of their patrons’ needs into harmonious and beautiful designs.

Arcadia University Landman Library, Glenside,

Pa., by R.M. Kliment & Frances

Halsband Architects, for Arcadia University

Arcadia University Landman Library, Glenside,

Pa., by R.M. Kliment & Frances

Halsband Architects, for Arcadia University

This design, in response to a competition for an addition to a university

library, placed a new wing at the south face of the existing library.

The resulting new, curved limestone building forms a distinctive presence

at the heart of the campus and accommodates 150,000 volumes; a multimedia

collection; the college’s archives; study seating for 300 in reading

rooms, carrels, and groups rooms; multimedia classrooms; and the trustees

room. The library strives to provide a variety of spaces and places for

reading and study, with controlled daylighting and campus views, including

a two-story-high reading room on the second floor that extends the full

width of the building and looks out over the campus green. The circulating

collection, housed on three floors in the older portion of the building,

is adjacent to the study areas and a small café.

Photo © Cervin Robinson.

Austin E. Knowlton School of Architecture Library—The Ohio State University,

Columbus, Ohio, by Mack Scogin Merrill Elam Architects with associate

architect Wandel and Schnell Architects, for the Ohio State University

Austin E. Knowlton School of Architecture

Austin E. Knowlton School of Architecture Library—The Ohio State University,

Columbus, Ohio, by Mack Scogin Merrill Elam Architects with associate

architect Wandel and Schnell Architects, for the Ohio State University

Austin E. Knowlton School of Architecture

When considering this library as part of the program for their school

of architecture, the faculty wanted to create an information and knowledge

resource that also could serve as a reflective space away from the work

environment of the design studios. This two-story glass-box, book-lined “room” accommodates

30,000 volumes and seating for 70 people in 40 table seats and 30 lounge

chairs—each designed by a famous architect or designer. The library

has an ample circulation desk with a closed reserve area, staff offices,

workroom and storeroom, copy room, reference and journal areas, digital

library, and rare book room. With “reading rooms” at either

end—and library services in the middle—the staff interacts easily with

the users and maintains control of the space. Located at the end of the

building’s circulation system, overlooking a roof garden, the library

is both very visible and removed from the major action of the building.

As a small indication of the library’s success, it drew more than

20,000 visitors in its first three months of operation while serving

a population of 750.

Photo © Timothy Hursley.

Carnegie

Library of Pittsburgh, Brookline, by Loysen + Kreuthmeier Architects,

for the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

Carnegie

Library of Pittsburgh, Brookline, by Loysen + Kreuthmeier Architects,

for the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

The architects were charged with turning a nondescript, two-story concrete

block with a zero lot line into a dynamic storefront library. The program

called for doubling the library’s space, which included expanding

the children’s department and adding an internet café, popular

library, and “self-help” stations. Daylighting the windowless

building proved the greatest design challenge, the architects say. A

new interior lining peels away from the rigid concrete shell and, with

the addition of a light wall, allows natural light from skylights and

clerestories to penetrate the spaces. To transform the low-ceiling basement

into a delightful children’s library, plaster ceilings tilt fancifully

to fit HVAC equipment. Although the library has doubled in size, the

new building, which has applied for LEED™ certification from the

U.S. Green Building Council, has a zero increase in energy consumption

over the old building.

Photo courtesy of the architect.

The Georgia Archives, Morrow, Ga., by Hellmuth, Obata + Kassabaum, for

the Development Authority of Clayton County

The Georgia Archives, Morrow, Ga., by Hellmuth, Obata + Kassabaum, for

the Development Authority of Clayton County

A highly specialized government entity, quartered in 17 stories of a

dark, monolithic building in Atlanta, asked the architects to create

a new building that would redefine the visibility of their mission to

the public. The architect’s first major intention was to design

around how the organization works. On a separate but parallel track,

the second major intention centered on designing for how visitors are

received and screened for security purposes and how they may enjoy the

education, research, and cultural opportunities presented. Operations

and public access are designed to be separate, meeting only at specific,

secure points. To supplement this technically rigorous program, the architects

sited the building to preserve existing stands of trees and the site’s

natural contours. Additionally important is the building’s pervasive

natural light, tempered with high-performance glass to eliminate UV penetration,

sunscreens, and porches.

Photo courtesy of the architect.

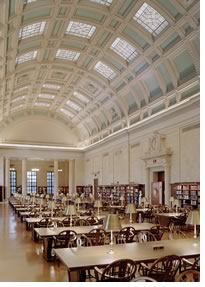

Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library

Renovation, Cambridge, Mass., by Einhorn Yaffee Prescott Architecture & Engineering

PC, for Harvard University

Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library

Renovation, Cambridge, Mass., by Einhorn Yaffee Prescott Architecture & Engineering

PC, for Harvard University

This 1915 library, designed by Horace Trumbauer, sits at the geographical

and intellectual heart of the university. In renewing the building for

the 21st century, the project called for a renovation that would “simultaneously

redefine the academic research library in programmatic and technical

terms without losing the aura, comfort, and connection to tradition.” The

first phase of the project entailed upgrading and modernizing the building

system infrastructure and the original 10-floor self-supporting stack

structure and library support spaces. New systems were threaded through

the stacks, and the architects “found” space within two large

light wells for new mechanical space, staff work areas, and two skylighted

reading rooms. The second phase involved restoration of the historic

public and reading spaces, in which existing features and room finishes

were preserved whenever possible.

Photo © Peter Aaron/ESTO Photographics.

Issaquah Public Library, Issaquah, Wash., by Bohlin Cywinski Jackson,

for the King County Library System

Issaquah Public Library, Issaquah, Wash., by Bohlin Cywinski Jackson,

for the King County Library System

This new 15,000-square-foot library offers its hometown an expansion

and modernization of library services in a more prominent and centralized

location in the historic downtown core. The cedar-sided structure used

an exaggerated building height to meet both the library’s programming

needs of one level and the city code’s call for multifamily urban

structures. A trellis and canopies help maintain human scale at the street

level. On the corner of the site is a large covered area, or agora, that

serves as a sheltered gathering place and marks the entrance to the building.

Activity in the library’s multipurpose room, adjacent to the agora,

is visible to the street. Doors open to the outside for special events.

Entering the building from the agora, one passes through a wood-lined

lobby and under a pair of tilted columns into the main space. Additional

round columns taper slightly as they rise to meet the wood-lined ceiling.

Light filters in the clerestory windows to highlight a delicate metal

truss at the spine of the building.

Photo © Fred Housel.

Salt Lake City Public Library, Salt Lake City, by VCBO Architecture

LLC, with design architect Moshe Safdie and Associates, for the Salt

Lake City Public Library

Salt Lake City Public Library, Salt Lake City, by VCBO Architecture

LLC, with design architect Moshe Safdie and Associates, for the Salt

Lake City Public Library

This 200,000-square-foot facility is part of an ambitious program by

the library to double its space for collections, establish a landmark

in the city’s civic core, and create a lively interactive public

space currently missing in the downtown area. The new library features

a triangular main building, adjacent rectangular administration building,

glass-enclosed “urban room,” and public piazza. Its reading

galleries, which replace the traditional formal reading room, accommodate

the “community of readers” in intimate spaces that are private

yet visually connected to magnificent exterior views. The library’s

sloped and curving wall has become an icon for the city, and the shops

and food establishments at its base weave the site together. The wall

also defines a connection to the city’s former library, which will

become an arts and science center. The library’s roof garden offers

spectacular views of the city and surrounding mountains. The library

also is a 2004 national AIA Honor Award for Architecture recipient.

Photo © Timothy Hursley.

Seattle Central Library, Seattle, by a joint venture of OMA/LMN (Office

for Metropolitan Architecture and LMN Architects), for the Seattle Public

Library

Seattle Central Library, Seattle, by a joint venture of OMA/LMN (Office

for Metropolitan Architecture and LMN Architects), for the Seattle Public

Library

The design goal for this library was to redefine the library as an institution

no longer exclusively dedicated to the book, but as an information story

in which all forms of media—new and old—are presented equally

and legibly. Unlike traditional libraries, Seattle Central Library is

organized into spatial compartments that are dedicated to and equipped

for specific duties. Each platform is a programmatic cluster that is

architecturally defined and equipped for maximum performance. The spaces

between the platforms function as trading floors where librarians inform

and stimulate. The library’s unique “book spiral” addresses

the ongoing problem of subject classification. For example, in 1920 the

library had no classification for computer science, but by the early

1990s the section had exploded. Using the Dewey Decimal System, the architects

arranged the collection in a continuous ribbon—running from “000” to “999”—the

subjects form a coexistence that approaches the organic. Each evolves

relative to the others, occupying more or less space on the ribbon, but

never forcing a rupture. The library also garnered a 2005 national AIA

Honor Award for Architecture.

Photo © Pragnesh Parikh.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

2005 AIA/ALA Library Building Awards Jury ALA: Anne Larsen Jonalyn Woolf-Ivory AIA: Sheila Kennedy, AIA Jeffrey Scherer, FAIA

|

||