National Museum of the

American Indian Takes Rightful Place on the Mall

Smithsonian’s newest gem speaks of

nature and diversity, acceptance and pride

by

Stephanie Stubbs, Assoc. AIA

by

Stephanie Stubbs, Assoc. AIA

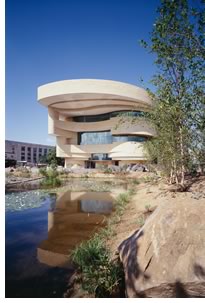

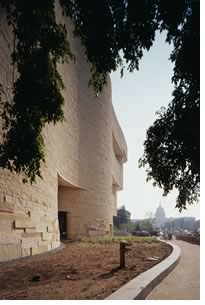

The revered Capital Mall in Washington, D.C., now stands complete, made whole by a building that is not like any of its neighbors. Its warm, honey-colored limestone contrasts with their cool marble. It is organically curved, caught in the flow of time, while they are rectilinearly reserved and geometric. This new National Museum of the American Indian speaks of love of nature, diversity and acceptance, and welcome. Its 254,000-square-foot, five-story presence is awesome and truly awe-inspiring, mystical and meaningful.

The National Museum of the American Indian, which opened September 21, pays tribute to cultures, though ancient, that are vibrantly alive today. The complex project was designed by an initial team that included GBQC and Douglas Cardinal Ltd., which included Douglas Cardinal, AIA (Blackfoot); Johnpaul Jones, FAIA (Cherokee/Choctaw); Donna House (Navajo/Oneida); and Ramona Sakiestewa (Hopi). The project was developed further by Jones, House, and Sakiestewa, along with architecture firms Jones & Jones; SmithGroup in collaboration with 2002 AIA Whitney Young Award winner Lou Weller, FAIA (Caddo) and the Native American Design Collaborative; Polshek Partnership Architects; and EDAW Inc. Landscape Architects.

The new building is the 16th museum in the Smithsonian family and takes

the last open museum space on the Capital Mall, making it “first

in line” to the U.S. Capitol and “profoundly aware of the

honor,” says Museum Director W. Richard West Jr. (Southern Cheyenne

and member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribe of Oklahoma). West has worked

to bring the project to fruition since 1989, when Congress passed a law

sponsored by then-Colorado Congressman Ben Nighthorse Campbell (Northern

Cheyenne) and Hawaii Senator Daniel Inouye establishing the National

Museum of the American Indian as part of the Smithsonian. Its objects

on display span 10,000 years, and, West says, the museum expects to serve

four million visitors per year.

The new building is the 16th museum in the Smithsonian family and takes

the last open museum space on the Capital Mall, making it “first

in line” to the U.S. Capitol and “profoundly aware of the

honor,” says Museum Director W. Richard West Jr. (Southern Cheyenne

and member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribe of Oklahoma). West has worked

to bring the project to fruition since 1989, when Congress passed a law

sponsored by then-Colorado Congressman Ben Nighthorse Campbell (Northern

Cheyenne) and Hawaii Senator Daniel Inouye establishing the National

Museum of the American Indian as part of the Smithsonian. Its objects

on display span 10,000 years, and, West says, the museum expects to serve

four million visitors per year.

The National Museum of the American Indian offers a glimpse of the complexities

of native cultures. Native Americans have taken the lead in all phases

of its planning, design, and construction. Thus, all parts of the project,

from surround to the smallest details of the exhibits, infuse meaning

and symbolism of significance to the continent’s first Americans.

The National Museum of the American Indian offers a glimpse of the complexities

of native cultures. Native Americans have taken the lead in all phases

of its planning, design, and construction. Thus, all parts of the project,

from surround to the smallest details of the exhibits, infuse meaning

and symbolism of significance to the continent’s first Americans.

Site and approach

The building is different right from its siting and approach. Instead

of being oriented north (Mall-side)/south (streetside), its main entrance

faces east to greet the morning sun. Its surround honors the earth

and nature with plantings, water, and rocks. Surrounding the building

are 40 Grandfather Rocks, uncarved boulders that represent longevity.

Also in evidence are the four cardinal direction markers, from the

far reaches of Native American communities: Hawaii (west); Northwest

Territories, Canada (north); Great Falls, Md. (east); and Puntos Arenas,

Chile (south).

The north ground on the mall side presents a hardwood forest and a waterfall.

On the south, in the crop area, beans, squash, and corn plants (the “Three

Sisters”) share ground with tobacco. On the east, or entrance side,

sits a serene wetland, complete with lily pads. Neighborhood fauna in

the form of Canada geese and green-headed mallards already seem comfortably

ensconced; their human counterparts still stand in awe.

The north ground on the mall side presents a hardwood forest and a waterfall.

On the south, in the crop area, beans, squash, and corn plants (the “Three

Sisters”) share ground with tobacco. On the east, or entrance side,

sits a serene wetland, complete with lily pads. Neighborhood fauna in

the form of Canada geese and green-headed mallards already seem comfortably

ensconced; their human counterparts still stand in awe.

It is from the east approach that the building form is at its purest and most spectacular. Above a circular, celestially patterned welcoming plaza, five stories of curved, cantilevered ridges evoke the timeless, windwashed feeling of massive cliffs and caves. It feels safe under those manmade cliffs, as though the architects worked with Mother Nature to create a sheltering, welcoming place.

Sacred space and object

Sacred space and object

Inside, the building immediately owns the notion that architecture is

space as much as object. Once through the security screening process

(sad, even if necessary), you stand in the soaring, sacred atrium named

The Potomac, which is to be used as ceremonial space. The 120-foot-tall

atrium celebrates the sun with a domed, glass-enclosed tension-ring

oculus that floods the space with light, supplemented with colors by

a huge prism set into the south wall. The stone-floor ceremonial platform,

100 feet in diameter, depicts the equinoxes and solstices. Its heart

is a red pipestone circle, representing fire. The ceremonial platform

is circled by a stone seating area and low, “woven” copper

wall, representing the importance of weaving.

Public spaces sharing the ground level with the Potomac include the store, dining hall, and the public auditorium, seating 322 people. Like many of the spaces, the auditorium engages all of the five senses (you can even smell pinon and cedar)—and some others that maybe don’t have English names. Director West describes the space as “the perfect storytelling vehicle: a clearing in the forest under the night sky.” Indeed, this space in the round with its vertical textured and detailed wood walls conjures up a pine forest, and the midnight blue acoustical ceiling, replete with twinkling “stars,” completes the effect. A surrounding lateral aisle allows actors into the audience, a necessary component of many American Indian performances.

The spirit is in the details

The spirit is in the details

The exhibit organization begins on the fourth level, with a 125-seat

Lelawi Auditorium that offers a knock-your-socks-off, 13-minute multimedia

introduction to the exhibits from a Native American perspective. This

theater, too, is round and ringed by stone seating benches. The beautifully

and carefully designed exhibits are singularly enhanced by the natural

simplicity of the interior architecture. The exhibits mainly populate

the third and fourth levels. The many smaller spaces-within-spaces

invite exploration at one’s own pace. For instance, the permanent “Our

Peoples” exhibit tells the stories of eight native groups in

their own words, literally. Reinforcing the notion that Indian culture

is alive and ongoing, audio components present Native Americans telling

the stories.

An “absence” of ceilings in the exhibit spaces helps give personal scale to the shows. Very high black ceilings allow for a variety of top closures in individual spaces, personalizing them and permitting evocation of a mixture of feelings. The collections, on the fourth and third floors, range from a totem pole to tiny carvings, each foiled to their own advantage.

Fine

attention to detail carries through to the working spaces on the second

floor and the Public Resource Center on the third floor, where tremendous

windows fill the space with light and allow spectacular views of the

surrounding Mall and Capitol grounds. Another nice touch: The cafeteria-style

public dining area (named “Mitsatam,” meaning “let’s

eat” in the Lenape language) features five geographically defined

Native American cuisines offering fare from cedar-planked salmon to cinnamon-spiked

frycakes. Thought-filled and graceful appointments filter all the way

down to this eating space, which is populated with bentwood chairs and

colorful fabric backdrops.

Fine

attention to detail carries through to the working spaces on the second

floor and the Public Resource Center on the third floor, where tremendous

windows fill the space with light and allow spectacular views of the

surrounding Mall and Capitol grounds. Another nice touch: The cafeteria-style

public dining area (named “Mitsatam,” meaning “let’s

eat” in the Lenape language) features five geographically defined

Native American cuisines offering fare from cedar-planked salmon to cinnamon-spiked

frycakes. Thought-filled and graceful appointments filter all the way

down to this eating space, which is populated with bentwood chairs and

colorful fabric backdrops.

The right time, a long time coming

At publication time, the Washington, D.C., area is in the midst of a

six-day First Americans Festival that began on September 21, the fall

equinox. Some 15,000 Native Americans took part in Native Nations Procession

on the Mall, followed by the grand opening of the museum. The building

stayed open all night of its first public night.

All buildings talk to architects; special buildings can talk to everyone.

The National Museum of the American Indian is one of those special buildings.

It places aside stereotypes and is saying perhaps now is the time to

be understood as much as to understand, for diversity to be embraced.

Throughout its structure and exhibitions, it demonstrates how American

Indian cultures teach expression of gratitude. Here is a magnificent

gift that can be shared by all who choose to walk through its doors.

Can we be grateful to be in the flow of time when this building is so

here, and so rightly here?

All buildings talk to architects; special buildings can talk to everyone.

The National Museum of the American Indian is one of those special buildings.

It places aside stereotypes and is saying perhaps now is the time to

be understood as much as to understand, for diversity to be embraced.

Throughout its structure and exhibitions, it demonstrates how American

Indian cultures teach expression of gratitude. Here is a magnificent

gift that can be shared by all who choose to walk through its doors.

Can we be grateful to be in the flow of time when this building is so

here, and so rightly here?

Copyright 2004 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

| Tour the

National Museum of the American Indian online. Due to its popularity, entrance to the museum currently is by timed passes, reserved at www.tickets.com, or calling 1-866-400-NMAI. A limited number of timed passes are available at the museum at 10 a.m. each morning. It must be said that the architect who created the magnificent design for the museum, Douglas Cardinal, left the project in 1998. On his Web site, Cardinal has posted the invitation from the museum’s director Richard West for Cardinal to attend the opening ceremonies, and Cardinal’s response.

|

||