09/2004

AIA North Carolina reports that for the second year in a row, architects from the Triangle area dominated the chapter’s competition, picking up eight of the nine presented design awards. The winning projects were selected from a field of 83 entries submitted by AIA members across the state. Though vastly differing in form and function, each project met or exceeded benchmarks of good architecture, according to jurors Julie Snow, FAIA; Chuck Knight, AIA; Ralph Rapson, FAIA; and David Salmela, FAIA, all principals with Minnesota firms.

Honor Awards

1409 Ashburton Road, Raleigh, by Architektur PA

1409 Ashburton Road, Raleigh, by Architektur PA

This new residence rose from the ashes of a home destroyed by fire. With

only the existing foundation walls remaining, the architect developed

a new parti based on the client’s contemporary lifestyle. While

respecting the context and scale of its 1950s ranch neighbors, the new

house embraces a modern vocabulary. A brick “private spine,” rests

on the existing foundations fronting the street and traverses the “public

spine,” setting up spaces for internal and external functions.

Volumes and voids define the residence’s indoor/outdoor spaces.

The new volumes are more open. For example a 16-foot sliding glass door

opens to a koi pond and Japanese-style gardens. Large expanses of operable

industrial-style windows harmonize with the neighbors’ fenestration

and allow the owners to capture cooling breezes. The architects also

used minimalist detailing of refined and unrefined materials to create

a warm and comfortable yet elegant environment.

Photo © James West.

Health Sciences Building, Wake Technical Community College, Raleigh,

by Pearce Brinkley Cease + Lee PA

Health Sciences Building, Wake Technical Community College, Raleigh,

by Pearce Brinkley Cease + Lee PA

Located adjacent to Wake Medical Center and the Wake County Health Department,

the 75,000-square-foot Wake Technical Community College Health Sciences

Building offers an academic and vocational facility for practicum training

of the college’s nursing program. The new building presents four

unique facades, each responding to its own context. The architects organized

the service core as a “solid” bar, buffering the program

spaces from the adjacent parking structure. Prominently located at a

roadway intersection, the building defines the corner edge of the medical

training complex. Its curtain wall, which is composed of three types

of glass, responds to this condition by turning the corner to front both

roads and simultaneously addressing the large scale of moving traffic.

The building houses the school’s dental hygiene program, EMS laboratories,

nursing laboratories, general teaching laboratories, assembly rooms,

classrooms, and administrative offices. Using a ring-corridor organization,

the architects placed offices and smaller classrooms on the perimeter

and larger laboratories and assembly rooms in the interior. Photo © James

West.

Webb Dotti House, Chapel Hill, N.C., by Gomes + Staub PLLC

Webb Dotti House, Chapel Hill, N.C., by Gomes + Staub PLLC

The curve of the street fronting this house’s lot inspired the

architects to site the building upslope, rather that along street edge.

They report that they translated the owner’s request for a landscaped

courtyard into “an elevated earthen terrace which aligns with and

provides views down the street corridor to the horizon.” They then

organized the interior spaces around and opening out to the garden terrace,

which ties the house to the land and creates a courtyard that engages

the neighborhood. The two pieces of the house are siblings, the architects

say, “composed of the same DNA, but nevertheless expressing individual

character traits.” The eastern house, slid downhill, has one level

and contains the living spaces. The western house, pulled uphill, has

two levels containing bedrooms and a study, and separates from the ground

at the back to form a covered carport. Between the two pieces is a glazed

slot of space which parallels the street axis, engaging the interior

and exterior spatial sequences. Photo courtesy of the architect.

Fort Hill, Home of John C. Calhoun, Clemson, S.C., by Harris Architects

Fort Hill, Home of John C. Calhoun, Clemson, S.C., by Harris Architects

Fort Hill, a National Historic Landmark and the plantation home of John

C. Calhoun and Thomas Green Clemson, is a symbolic focal point of the

Clemson University Campus. First constructed in 1802, with numerous

additions through the mid-19th century, it currently serves as

a museum. This project included a detailed restoration of the house,

law office, and grounds that began with a written master plan. The

first two phases of construction were completed and included exterior

restoration, lead paint abatement, cypress shingle roofing, structural

stabilization, and complete new building systems. The second phase

of the work restored interior finishes such as plaster, decorative

painting, and wallpaper reproduction of papers specific to the house.

Detailed in the Greek Revival style, Calhoun’s home, his primary

residence, contained many fine furnishings that remain with the house.

It was finished to match period tastes and his stature in life, and

the challenge, the architects say, was to balance the client’s

program of restoring the buildings to their 1827–1850 appearance

while introducing all new building systems, including a sprinkler system,

and meeting current code requirements. Photo courtesy of the architect.

Merit Awards

Tyndall Gallery, Chapel Hill, N.C., by Philip Szostak Associates

Tyndall Gallery, Chapel Hill, N.C., by Philip Szostak Associates

This 2,500-square-foot retail fine-arts gallery was relocated to a traditional

mall. Its program sought to maximize the flexibility of the display areas

as well as optimize the art storage, framing gallery, and office areas.

To create a gallery that enhances the artwork, the architects manipulated

the scale of the various gallery areas. They started with a 24-foot height

and inserted a multilayered, painted sheetrock series of planes that

varied in height and thickness. They then tempered the gallery walls

with “the cloud,” a ceiling element that lowered the scale

of one of the main display walls for smaller paintings. The cloud also

defines a front-to-back axis to another display wall for a focused presentation.

Blue lighting above the cloud helps lift the space and further challenges

the scale of the more open space. Because of the incredibly tight budget,

the architects acted as construction managers, taking budget control

responsibility. Photo © Philip Szostak.

Buffaloe Road Athletic Park, Raleigh, by BBH Design (the former office

of NBBJ, NC)

Buffaloe Road Athletic Park, Raleigh, by BBH Design (the former office

of NBBJ, NC)

The architect designed two small structures for phase one of a city park—a

500-square-foot bathroom building and a 3,500-square-foot maintenance

shed—in response to the client’s request for a solution that

could address current functional criteria and adapt to different roles

in the future. The building’s “primitive shed” parti

connects to the spirit of the place through two concepts: memory and

reciprocity. As part of a vernacular tradition, the shed form registers

with the collective memory of the farmland it now occupies, as many of

these shed forms still populate rural North Carolina. Additionally, a

reciprocal relationship between the exterior and interior space is established

by assigning the same value to each. Each shares the shelter of the overhead

plane and is situated to encourage fluid movement between the inside

and outside, according to the architect. Both the typology and materials

of the project are native to and inseparable from the site. Photo © James

West.

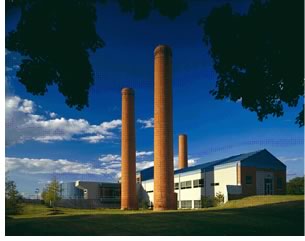

Durham Solid Waste Operations Facility, Durham, N.C., by The Freelon

Group, Inc.

Durham Solid Waste Operations Facility, Durham, N.C., by The Freelon

Group, Inc.

The City of Durham Solid Waste Operations Facility wanted a new complex

on the site of a 1930s incinerator that had been shut down for environmental

concerns in the 1960s and sat dormant ever since. The architects calculated

that the owner’s program and budget could be accommodated in the

existing building’s 22,000 square feet, plus 4,500 square feet

of new construction. The existing building’s three floors now contain

administrative offices, conference rooms, locker and shower rooms, an

exercise room, a break room, and toilet/mechanical rooms, while the new

adjoining construction consists of a 150-seat auditorium, main building

entrance lobby, and elevator tower. The design incorporates all of the

old incinerator building’s existing brick and concrete walls and

floors, and three tall brick smokestacks remain as icons in the landscape.

Existing large exterior wall openings now sparkle with glazing and let

natural light shine in, while the new construction is wrapped in corrugated

metal panels and a metal standing-seam roof. Photo © James West.

U.S. Food & Drug Administration Life

Sciences Laboratory, White Oak, Md., by Kling

U.S. Food & Drug Administration Life

Sciences Laboratory, White Oak, Md., by Kling

This project makes up the first phase of a new federal campus that will

consolidate FDA facilities presently housed in more than 40 locations.

The Life Sciences Lab houses chemical and biological analytical labs

for two of the agency’s four review centers. Its metal-panel and

glass cladding reflect the function of the lab technology that lies as

the core mission of the agency, the architects say, and its siting and

massing reflect the specific site relationships of the building within

the master plan. This new federal campus for 8,000 FDA researchers will

transform a decommissioned Navy Ordnance research facility into the new

home for the agency. The central core of the building houses the laboratories,

expressed by the penthouse mass that extends above the roof and encloses

the exhaust stacks. Linear rows of offices are laminated onto each side

of the lab core, which are expressed with horizontal windows articulated

to accommodate varying office modules. The building layout provides light-filled

interiors, even within the interior lab spaces, and provides informal

work areas at opposite corners of the building to encourage interaction

among the scientists. Photo © Ron Solomon Photography.

Unbuilt Merit Award

Phillips House, North Wilkesboro, N.C., by Kenneth

E. Hobgood, architects

Phillips House, North Wilkesboro, N.C., by Kenneth

E. Hobgood, architects

This 600-square-foot weekend house in the mountains will perch close

to the road on the bank of a stream that runs along the east boundary

of its 300-acre site so that most of the site will be untouched and

available for hiking. With the exception of its poured foundations

and one site wall, most of the house will be fabricated off site to

preserve the natural beauty of the parcel. The architects designed

the house to be constructed in four linear site-assembled sections.

Composing the four frames of the house, the sections all run in the

north-south direction, defining linear spaces constructed and spaced

by function. The metal frame facing the entrance to the site visually

contains the elements of the house and provides exterior screens that

provide privacy and sun control for the house. Photo courtesy of the

architect.

Copyright 2004 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()