The Aegean Crucible—Tracing Vernacular Architecture in Post-Byzantine Centuries, by Constantine Michaelides, FAIA

reviewed by Lou Saur, FAIA

The

Aegean Crucible, by Constantine “Dinos” Michaelides,

offers an inspired, meticulous portrait of the vernacular architecture

of the Aegean Islands. Michaelides first encountered the subject as an

undergraduate student at the School of Architecture at the National Technical

University in Athens. There he met Professor Pikinious, who said of vernacular

architecture: “Unaffectedness [is] one of the great merits of the

folk vernacular tradition and, by extension, of ancient and medieval architecture.

Although one might fail to find great art in it one would certainly find

natural, that is, true art.”

The

Aegean Crucible, by Constantine “Dinos” Michaelides,

offers an inspired, meticulous portrait of the vernacular architecture

of the Aegean Islands. Michaelides first encountered the subject as an

undergraduate student at the School of Architecture at the National Technical

University in Athens. There he met Professor Pikinious, who said of vernacular

architecture: “Unaffectedness [is] one of the great merits of the

folk vernacular tradition and, by extension, of ancient and medieval architecture.

Although one might fail to find great art in it one would certainly find

natural, that is, true art.”

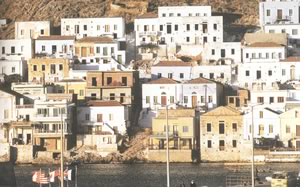

While vernacular architecture can best be explained as a system of architectural expression native to a particular place and people, in the Aegean Islands it takes on an additional, richer meaning. The area’s architecture evolved over centuries into an exquisitely beautiful art form expressed in whitewashed, terraced houses and chapels grouped into collective forms of habitations in myriad ways. This plastic continuity of form together with the changing light of the Aegean archipelago brings to mind again Le Corbusier and his poetic definition of architecture as “the masterly, correct, and magnificent play of masses brought together in light.” Michaelides has dedicated a lifetime to understanding, and now explaining, the human and natural influences that shaped these enchanting structures into a vernacular architectural language. He calls the response to these influences by the island inhabitants the “crucible.”

Mythical

and mystical influences

Mythical

and mystical influences

The Aegean archipelago possesses a transcendent mythical quality. Formed

by volcanoes still active, it is believed that Plato’s mythical

City of Atlantis crumbled into the sea as the island of Crete imploded.

It is said to be the site of the Homeric tale of Ulysses’ journey

of self-discovery and the location of the Colossus of Rhodes, one of the

seven wonders of the Ancient World. St. John wrote the Book

of Revelation, the final book of the New

Testament on the Island of Patmos. Michaelides infers that the

mystical quality that inspired those ancient tales also could have inspired

its nameless builders.

The geological, geographic, and climatic qualities of the Archipelago Islands supply a second set of influences in the Michaelides’ Crucible. The climate supports year-round outdoor living, making the islands attractive for human habitation in current as well as ancient times. The bright and unfiltered sunlight, similar to that of the American Southwest, makes objects sharper and colors more vivid. The 83 or so islands composing the archipelago physically are variations on a theme: All are mountainous with steep, rocky terrain and minimal vegetation. They also dramatically embrace the water in intricate shorelines of bays and harbors.

The

need for trade and communication dictate a strong relationship between

the sea and habitation, because the islands do not offer a self-sustaining

environment for human life. The winter winds generated by the temperature

variation in this region create some unpleasant climatic effects. Very

low annual rainfall creates little fresh water, thus, inhabitants design

all manmade surfaces to collect and distribute water to cisterns. Although

rock is plentiful for wall construction, wood beams for roofs are scarce.

There are also seismic considerations. But all views are spectacular,

revealing unyielding poetic beauty.

The

need for trade and communication dictate a strong relationship between

the sea and habitation, because the islands do not offer a self-sustaining

environment for human life. The winter winds generated by the temperature

variation in this region create some unpleasant climatic effects. Very

low annual rainfall creates little fresh water, thus, inhabitants design

all manmade surfaces to collect and distribute water to cisterns. Although

rock is plentiful for wall construction, wood beams for roofs are scarce.

There are also seismic considerations. But all views are spectacular,

revealing unyielding poetic beauty.

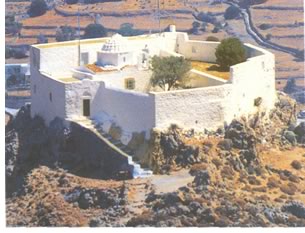

The geopolitical history of the region, including economic and religious factors, encompasses a third set of influences in the Crucible. Suffice it to say the islands experienced tumultuous political change and upheaval from ancient to modern times. The book’s many maps make it immediately apparent that the Aegean archipelagos reside in the center of a body of water that extends from Gibraltar and the Atlantic Ocean to the Black Sea, a location convenient to many competing social/political interests since the beginning of recorded history. Building for defense, therefore, was paramount to island builders who for economy’s sake bunched their dwellings together to share the walls for common defense. They also built high on the mountains for visibility and inaccessibility, and created irregular urban forms to confound and trap their assailants. They did all this in ways that allowed them to live convenient and productive lives when they were not being externally threatened.

Testimony

to human ingenuity

Testimony

to human ingenuity

In the second half of the book, Michaelides becomes the articulate architect/craftsman.

He gratifies the reader with graphically rich explanations of how and

why these island habitations evolved into a unique vernacular architecture.

He explores all types of buildings, from formal structures such as monasteries

and chapels, to utility structures such as windmills and dovecotes. He

also examines all aspects of architecture from construction methods to

floor plans and sections, to details such as windows, doorways, identifying

icons, steps, and even paint colors.

One

could argue the archipelagic architecture offers a testimony to human

ingenuity in creating beauty from limited resources and adverse conditions.

That may be one of the book’s themes, but it is not the most interesting

one to me nor, do I believe, to the author. This book enlightens and entertains,

but the author also seeks to engage readers by opening many avenues of

thought. Michaelides invites readers to share his curiosity and form their

own conclusions from the many possibilities he presents. Following are

some of my conclusions, supported by quotations from the book:

One

could argue the archipelagic architecture offers a testimony to human

ingenuity in creating beauty from limited resources and adverse conditions.

That may be one of the book’s themes, but it is not the most interesting

one to me nor, do I believe, to the author. This book enlightens and entertains,

but the author also seeks to engage readers by opening many avenues of

thought. Michaelides invites readers to share his curiosity and form their

own conclusions from the many possibilities he presents. Following are

some of my conclusions, supported by quotations from the book:

- A poetic impulse inspires great works of architecture. “When gazing on this rock-built city in the stillness of the evening, it appeared to me one of the most striking objects on which my eyes have ever rested." Places of great natural beauty, whether manmade or natural, strike reverence into the hearts of persons seeking to intervene, and should thereby invoke a parallel poetic response. This makes a convincing argument against the formula buildings so ubiquitous in the contemporary American landscape.

- Architecture grows from deeply rooted cultural and natural influences sympathetically interpreted, not from the latest fads or an appetite for novelty. This is an important contrast to what influences architecture in 21st century America.

Limited

resources thought in most instances to be a liability, if understood

properly, can in fact be an asset by stimulating a more natural and

less pretentious way of responding to the needs of life.

"An intelligent response to both abundance and limitation is characteristic

of the ethos of the vernacular builders of the archipelago."

Limited

resources thought in most instances to be a liability, if understood

properly, can in fact be an asset by stimulating a more natural and

less pretentious way of responding to the needs of life.

"An intelligent response to both abundance and limitation is characteristic

of the ethos of the vernacular builders of the archipelago."- A system for making things that simultaneously permits variety and unity achieves a transcendent quality in which the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. "Unity in the small number of decorative elements and variety in the numberless ways these elements are assembled is addressed masterfully by the island builders."

- The impulse to preserve these structures and reuse them for modern purposes indicates both their appeal and versatility, or timeless quality. "The Aegean island chapels and churches are thus apparently ageless, as it is difficult to discern in which a particular church or chapel was built."

Copyright 2004 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

| To order The Aegean Crucible, call the AIA St. Louis Bookstore, 866-463-2954. Author Constantine Michaelides, FAIA, is an architect, educator, and former dean of the Washington University School of Architecture. A native of Greece and a St. Louis resident for the past 40 years, he was elevated to Fellow of the AIA for his contribution to architecture education. Reviewer Louis R. Saur, FAIA, is principal of Saur and Associates Architects and president of AIA St. Louis.

|

||