WWII Memorial Dedicated

on the Mall

More than 100,000 of the “Greatest

Generation” take part

by Stephanie Stubbs, Assoc. AIA, and Douglas E. Gordon, Hon. AIA

May

29, 2004, a truly glorious day, brought an azure sky, bright sun, and

cool breezes to the nation’s capital, where more than 100,000 people,

a good number of them World War II veterans, witnessed the dedication

of the World War II Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

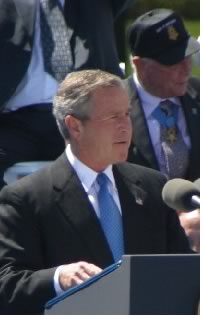

Just after 3 p.m., General Francis P.X. Kelley (U.S. Marine Corps-retired),

chair of the American Battle Monuments Commission, presented the memorial

to President George W. Bush, who accepted it on behalf of the American

people.

May

29, 2004, a truly glorious day, brought an azure sky, bright sun, and

cool breezes to the nation’s capital, where more than 100,000 people,

a good number of them World War II veterans, witnessed the dedication

of the World War II Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Just after 3 p.m., General Francis P.X. Kelley (U.S. Marine Corps-retired),

chair of the American Battle Monuments Commission, presented the memorial

to President George W. Bush, who accepted it on behalf of the American

people.

Among his remarks, the President said, “It is a fitting tribute, open and expansive like America itself, grand and enduring like the achievement we honor. … We will raise the American flag over a monument that will stand as long as America itself.” This new monument, by design architect Friedrich St. Florian, AIA; architect of record Leo A Daly; and associate design architect Hartman-Cox, captures the open generosity that marks the best of the American spirit, personified by the veterans of World War II.

The monument indeed is physically open, with two-thirds of its seven acres of prime Mall land devoted to landscaping and water in the form of pools and fountains. It beckons you in via a wide expanse along its streetside entrance, and tells you that you too play a part in its story from the moment you set foot on its ground. Its honest and clean elements tell you that despite serious tribulations along the way, the optimistic American spirit that prevailed some 60 years ago is alive and unvanquished to this day, even by the horror of September 11, 2001.

Siting

on the Mall

Siting

on the Mall

Its critics first find fault with the location of the memorial, which

sits on the restored Rainbow Pool site at the east end of the Reflecting

Pool, halfway between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument.

Congress, the National Park Service, the Commission of Fine Arts, and

the National Capital Planning Commission all approved siting of the World

War II Memorial in this prime position on the National Mall, revitalizing

the Rainbow Pool site, which had been inactive, its fountains dead and

desiccated for a decade.

The

entrance entablature to the memorial itself explains the reasoning behind

the memorial’s placement: “Here in the presence of Washington

and Lincoln, one the eighteenth century father and the other the nineteenth

century preserver of our nation, we honor those twentieth century Americans

who took the struggle during the second World War and made the sacrifices

to perpetuate the gift our forefathers entrusted to us, a nation conceived

in liberty and justice.”

The

entrance entablature to the memorial itself explains the reasoning behind

the memorial’s placement: “Here in the presence of Washington

and Lincoln, one the eighteenth century father and the other the nineteenth

century preserver of our nation, we honor those twentieth century Americans

who took the struggle during the second World War and made the sacrifices

to perpetuate the gift our forefathers entrusted to us, a nation conceived

in liberty and justice.”

The very openness of the memorial and lowering of its site save it from diminishing the bond between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial. Carefully and unobtrusively placed, with its two 43-foot-tall quadruple arches honoring the Atlantic and Pacific war theaters set well north and south of the main vista, respectively, the memorial does not, as feared, block views from Washington to Lincoln or vice versa. Within the memorial itself, low cutouts frame head-turning views of the Lincoln Memorial, inspiring a fresh thrill for Henry Bacon’s masterpiece, even for one who has seen it a thousand times.

There

is one spot, however, with a slightly disorienting effect: If you stand

directly center of the nine-foot-tall gold-starred Wall of Freedom, the

Lincoln Memorial disappears completely from view. You find yourself immersed

in a vertical field of 4,000 gold stars, each representing 100 U.S. soldiers

who lost their lives in action—a gold star in the window during

the war meant the household had lost a family member. Look down, and 4,000

gold stars shimmer back at you, reflected in a calm pool of water. It

is a deliberate effect, as St. Florian explains in a Washington

Post article: “Standing here at the base of the Freedom Wall,

the view to Lincoln is purposefully obstructed in order to focus on the

sacrifices made by World War II’s generation. At this moment, here

is the only place you are.”

There

is one spot, however, with a slightly disorienting effect: If you stand

directly center of the nine-foot-tall gold-starred Wall of Freedom, the

Lincoln Memorial disappears completely from view. You find yourself immersed

in a vertical field of 4,000 gold stars, each representing 100 U.S. soldiers

who lost their lives in action—a gold star in the window during

the war meant the household had lost a family member. Look down, and 4,000

gold stars shimmer back at you, reflected in a calm pool of water. It

is a deliberate effect, as St. Florian explains in a Washington

Post article: “Standing here at the base of the Freedom Wall,

the view to Lincoln is purposefully obstructed in order to focus on the

sacrifices made by World War II’s generation. At this moment, here

is the only place you are.”

A complex simplicity

Some critics have said the monument is “fascistic,” especially

its side arcs of 17-foot-tall white pillars. We don’t find it so

at all. These 56 granite sentinels make the memorial more democratic.

Each is carved with the name of a state or territory and bears a brace

of bronze wreaths—one of oak leaves, the other wheat—representing

the importance of the states’ agriculture and industry to the war

effort. The memorial skillfully blends into an understated simplicity

elements of the neo-Classical City Beautiful Movement (adopted by the

McMillan Plan in 1902, led by the AIA, as the style for the National Mall)

with the pre-War WPA style that touches much of federal Washington.

Some critics also have called the memorial “colorless.” It is deliberately and quietly respectful of its neighbors. Perhaps the critics looked before it transformed into the stage for visitors it is intended to be. The memorial breathes in its color from its visitors and the mementos they already have started to leave: flowers, cards, and copies of old photographs. The people know, instinctively, that they are a part of the memorial.

A

range of emotion

A

range of emotion

Ray Kaskey, FAIA, is the subtle genius behind the 4,000 sculpted stars

of the Freedom Wall, the two wreaths on each of the 56 pillars, and the

bronze ropes that tie the pillars together. The sculptor has given us

24 bronze bas-relief sculptures along the ceremonial entrance, each depicting

a different aspect of life during the war. He and his studio also have

brought to life the two baldachinos within the Atlantic and Pacific arches,

each composed of four bronze columns, and four magnificent bronze eagles

sharing the task of lifting a gigantic laurel wreath suspended by ribbons.

Like the architectural elements, the bronzes use their symbolic simplicity

to capture the essence of a very complex message.

Some critics have said that the World War II Memorial is not as emotionally evocative as the stark black granite Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Perhaps that is true. The Vietnam memorial, built less than 10 years after that war ended, had a more proximate vantage of its subject. It served as a reflexive, healing hand on a fevered national brow. In contrast, the World War II memorial harkens back some 60 years in time and light years in technological changes. Perhaps it just has a more complex story to tell, tempered by time and the growing perspective of its aging participants. Perhaps its range of emotions is greater, meaning it needs a much broader middle ground.

Creating

community

Creating

community

If architecture is about creating community, the World War II memorial

offers us successful architecture. Simply stand at the perimeter and watch

the flows and eddies of visitors. Kids scamper and leap in inspired awe;

veterans in wheelchairs move slowly with tears in their eyes around this

open arena for shared learning from the memorial and from each other.

If architecture is about creating experience, the memorial offers us another

kind of success. It truly is an experiential space (very difficult to

photograph) that can only be known by traversing its distance and marking

its cadence, slowly spiraling down to its heart of golden stars. If architecture

is about touching the people it serves, the memorial indeed serves well.

If in doubt, ask the veterans whom it honors.

On Dedication Day, we had the opportunity to ask the vets—as did many other ordinary people, as well as critics and reporters whose accounts you may read—what they thought. The veterans, taking the memorial personally and to heart, might have said it is too big, too cold, too long overdue, too simplistic, too monumental. To a person, though, they simply said “it’s beautiful.” And, of all things, “thank you.”

Thank you, great generation. This monument’s for you.

Copyright 2004 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()