Win-Win Ecology: Food

for Architects’ Thoughts

Author suggests ways to save wild species

reviewed by Tracy Ostroff

“There

is still time,” author Michael L. Rosenzweig, PhD, notes in his

upbeat book Win-Win Ecology How the Earth’s

Species Can Survive in the Midst of Human Enterprise (Oxford University

Press, 2003), to implement solutions that work for our environment at

the same time they work for business interests. Rosenzweig’s approach

of “reconciliation ecology,” which he explains is the “science

of inventing, establishing, and maintaining new habitats to conserve species

diversity in places where people live, work, or play,” doesn’t

presume that we should surrender our creature comforts or turn back progress

that already has been made through conservation and restoration. Rather,

the author says, we can share our spaces through cooperation, planning,

and, sometimes, happy accident.

“There

is still time,” author Michael L. Rosenzweig, PhD, notes in his

upbeat book Win-Win Ecology How the Earth’s

Species Can Survive in the Midst of Human Enterprise (Oxford University

Press, 2003), to implement solutions that work for our environment at

the same time they work for business interests. Rosenzweig’s approach

of “reconciliation ecology,” which he explains is the “science

of inventing, establishing, and maintaining new habitats to conserve species

diversity in places where people live, work, or play,” doesn’t

presume that we should surrender our creature comforts or turn back progress

that already has been made through conservation and restoration. Rather,

the author says, we can share our spaces through cooperation, planning,

and, sometimes, happy accident.

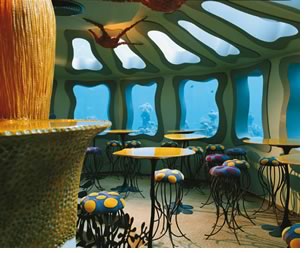

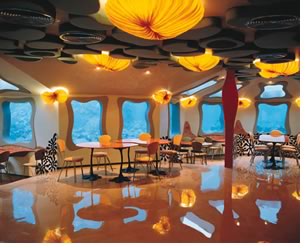

Win-Win Ecology’s 211 pages are replete with examples, notes, and anecdotes describing how this balance can be achieved and how the equilibrium of ecology and development has helped save endangered species in this country and worldwide. He introduces his research through an example of Eliat, Israel, a city with a coral reef that serves as home to a stunning array of marine life but has been diminished by a steady stream of tourism and economic development. “Imagine my surprise then when the travel section of our local newspaper told about the new Red Sea Star Restaurant in Eliat. It would soon open, underwater and surrounded by coral reef!” Disbelieving, Rosenzweig went to see it for himself on a research trip to Israel.

“What

we saw when the elevator opened made us tingle with awe and disbelief

“What

we saw when the elevator opened made us tingle with awe and disbelief

. . . Half the floor was a cocktail bar, and half, an elegant, white-tablecloth

restaurant. Natural light streamed in from the see-through portholes in

the ceiling and fancifully shaped windows that lined the entire structure.

Outside those windows was a coral reef full of the gorgeous fish and other

lovely animal species that inhabit the reserve several miles away.”

Further investigation led Rosenzweig to discover that the coral surrounding

the restaurant were actually those that had been damaged or diseased,

and were recuperating after been treated with antibiotics at a coral hospital.

“Some, after recuperation, go to the Red Sea Star Restaurant. There

divers wire them to a meshwork of iron cloth where they start to grow,

soon covering and enveloping their artificial iron matrix. The fish simply

volunteer. As they say, if you build it, they will come. Presto, reconciliation

ecology.”

Other examples of reconciling our land to promote wild species include homeowners who create a backyard wildlife habitat and city parks and gardens, such as Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, that serve as an oasis for its human visitors as well as its wild company. Rosenzweig points to efforts that provide ponds for recreation spots, including model boating. “But no one will cry interference if we help the song sparrows by allowing a few more shrubs in the understory around the ponds. And no one should mind if more vegetation overhangs the ponds to help the kingfishers and the black phoebes.” The author also points to the green roofs and roof gardens as an urban solution for reconciliation ecology. “Why not enlist the roofs of the world’s cities in the campaign to save species. Who knows how many we could help if we varied the design of the gardens?” the author queries.

Sharing is good

Rosenzweig believes that without reconciliation ecology, “diversity

is doomed.” But he also is sensitive to those who think this book

tramples on “green” causes. He says the theories in Win-Win

Ecology can saddle up alongside the more traditional sustainable

and environmental practices and provide a common ground to “reduce

the endless bickering and legal wrangling that characterize environmental

issues today.” It gives us a mechanism for sharing the land with

nature as opposed to parceling it out for distinct purposes. Throughout

the book, he points to examples of how, with a little bit of planning,

species habitats have been maintained at the same time development has

continued and thrived. Even a duo of talking pocket mice makes its case

for Rosenzweig’s theories.

- Florida’s Eglin Air Force Base is a test site for President Reagan’s Star Wars initiatives that is also home to many rare species of plants and animals—particularly the longleaf pine and the species that depend on it—thanks to a partnership between the U.S. Department of Defense and the Nature Conservancy. Having restored the longleaf pine habitat, managers at the base also turned their attention to the endangered red-cocked woodpecker by drilling artificial woodpecker-nest cavities in the pine tree’s trunks.

- Back in Eliat, Israel, development there—luxurious hotels, nightlife, a boardwalk, shopping, and more—were decimating the salt marsh to which the birds of the city had become accustomed. That was until Dr. Reuven Yosef, director of the International Birdwatching Center of Eliat, decided to take a tract of wasteland and develop it into a new salt marsh for his feathered friends. “Yosef had a vision. Put a few hundred tons of landfill here and there, scrape it into dikes, cut a channel to allow some seawater in, plant some of the right species of shrubs and voila!, you would have an artificial salt marsh complete with open water areas.” Yosef struck a deal to use the dirt from the hotel construction sites to create the artificial salt marsh.

- In a piece for the University of Arizona alumni magazine, Rosenzweig notes that Chicago Mayor Richard Daley is taking 19 abandoned gas stations and turning them into “pocket parks—little areas for birds, flowers, and trees.”

Money and science

In the opening of the “Making Money” chapter, the author asks,

“Will reconciliation ecology cost money or make money?” Although

Rosenzweig does go on to show the cost benefits of reconciliation ecology,

he also notes: “Yet I have to begin the money chapter by insisting

that this question must never be allowed to belittle people and their

dreams. Yes, the money question is important. But I am certain that we

worry about diversity for the best reasons: aesthetics and ethics.”

Rosenzweig also makes his case for the economic benefits of reconciliation

ecology through more examples, including those of the restaurant and salt

marsh in Eliat, and of the Mormon Church, which sells hunting rights to

help manage the game species and allow hunters to hunt their prey legally.

Later in the book, Rosenzweig turns more explicitly to science to show

the problems that diversity faces. With a professor’s patience,

he lays out charts and graphs that describe species-to-area relationships

and explains why this connection is at the heart of determining how much

land we set aside for wild species.

Rosenzweig also makes his case for the economic benefits of reconciliation

ecology through more examples, including those of the restaurant and salt

marsh in Eliat, and of the Mormon Church, which sells hunting rights to

help manage the game species and allow hunters to hunt their prey legally.

Later in the book, Rosenzweig turns more explicitly to science to show

the problems that diversity faces. With a professor’s patience,

he lays out charts and graphs that describe species-to-area relationships

and explains why this connection is at the heart of determining how much

land we set aside for wild species.

A special message for architects

Rosenzweig is especially keen for architects to hear his message because

he wants to give design professionals the tools to do a project within

the next five years that incorporates reconciliation ecology. In an interview

at the AIA national component, Rosenzweig said architects have the training

to understand that sprawl and development create opportunities for saving

and enhancing the earth’s wild species. Architects can start by

going to the local university to research species that are native to the

area and to find out what their natural habitats would look like. “It

wouldn’t take much more effort to implement these solutions.”

For example, it could be as easy as encouraging a client to install a

green roof if the project lends itself to such an addition, or creating

nest boxes for bluebirds in a residential project.

For Rosenzweig, this is a worthwhile cause that is a spiritual journey

routed in moral duty to do right by his planet. “Our love for natural

diversity has deep roots,” he writes. And it is clear that Rosenzweig’s

love is profound.

Copyright 2004 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

|

Photos of the Red Sea Star Restaurant courtesy of Ayala Serfaty, Aqua Gallery Ltd. Serfaty designed the restaurant’s interiors. According to the restaurant’s Web site, The Red Sea Star was designed by the architect Sefi Kiryaty, with structural engineers Moshe Dreemer and Nitai Dreemer.

|

||