Brown Earns 2004 Whitney

Young Award

Architect’s work touches those in

need overseas and in the U.S.

by Heather Livingston

The AIA named Terrance J. Brown, FAIA, as the recipient of the 2004 Whitney M. Young Jr. Award, given to an architect who exemplifies the profession’s responsibility to society. The award honors Whitney Young Jr.—head of the Urban League from 1961 until his death in 1971—who, at the 1968 AIA national conference, chided the audience of architects and challenged them to become a positive force for social change: “You are not a profession that has distinguished itself by your social and civic contributions to the cause of civil rights. You are most distinguished by your thunderous silence and your complete irrelevance.”

From

his childhood among the Crow Indians of Montana to his work with Mayans

and Native Americans, and now as the AIA ambassador to Latin America and

the Caribbean on the Pan American Federation of Architects, Brown has

dedicated his life to serving his fellow humans and his profession with

respect, integrity, dignity, and compassion. In nominating Brown for this

award, Barbara A. Nadel, FAIA, former AIA vice president, wrote, “For

over 30 years, this remarkably talented man has demonstrated what a single

architect can do to change the world and make the global community a better

place to live.”

From

his childhood among the Crow Indians of Montana to his work with Mayans

and Native Americans, and now as the AIA ambassador to Latin America and

the Caribbean on the Pan American Federation of Architects, Brown has

dedicated his life to serving his fellow humans and his profession with

respect, integrity, dignity, and compassion. In nominating Brown for this

award, Barbara A. Nadel, FAIA, former AIA vice president, wrote, “For

over 30 years, this remarkably talented man has demonstrated what a single

architect can do to change the world and make the global community a better

place to live.”

Globally aware

Brown’s contributions to the global community are well known to

those he has aided. A highly decorated officer in Vietnam, Brown subsequently

traveled to Central and South America, where he worked with hundreds of

volunteers from the U.S. Peace Corps, United Nations, Japan, Canada, and

the U.S. Embassy to help them adapt to new environments and begin their

work in impoverished rural villages. While there, he co-founded a linguistics

center in Guatemala to help revitalize and preserve the country’s

22 Mayan languages. A testament to his vision, the Proyecto

Linguistico Francisco Marroquin schools still continue to help

Mayans create grammar, alphabets, and dictionaries in their own languages.

While

in Guatemala, Brown also oversaw emergency rescue efforts following a

devastating earthquake in 1976. He helped move the public hospital to

a safe location and organized and constructed a temporary hospital for

hundreds of patients. Since that time, he has conducted disaster surveys

in St. Lucia following a hurricane that destroyed all their public buildings

and assisted with assessments after the Los Alamos fires in 2000. Brown

has now teamed with Charles Harper, FAIA, chair of the AIA Disaster Response

Committee, to offer a seminar on disaster assistance at the AIA National

Convention in Chicago this June.

While

in Guatemala, Brown also oversaw emergency rescue efforts following a

devastating earthquake in 1976. He helped move the public hospital to

a safe location and organized and constructed a temporary hospital for

hundreds of patients. Since that time, he has conducted disaster surveys

in St. Lucia following a hurricane that destroyed all their public buildings

and assisted with assessments after the Los Alamos fires in 2000. Brown

has now teamed with Charles Harper, FAIA, chair of the AIA Disaster Response

Committee, to offer a seminar on disaster assistance at the AIA National

Convention in Chicago this June.

Culturally sensitive

Upon returning to the U.S., Brown began working with Weller Architects,

an American Indian-owned practice in New Mexico. He infuses his work in

the American Southwest with cultural sensitivity and has enabled rural

tribes and pueblos to improve the quality of medical and educational facilities

without compromising their cultural values and traditions. Brown firmly

believes that designing with tribal and pueblo community participation

results in facilities that respond to communal needs yet respect beliefs

and lifestyles. He encourages local tribal artists to enhance his designs

with sculptures, weavings, and paintings that represent their culture

and incorporate elements of tribal spirituality and healing.

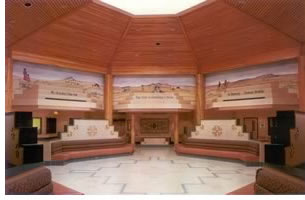

Among

Brown’s award-winning projects is the Taos-Picuris Pueblos Health

Center in Taos Pueblo, N.M. Urged by tribal leadership to create a facility

that “feels like home, yet provides the ultimate best in modern

health care,” Brown used natural materials and integrated symbolically

significant elements of earth, sky, hearth, and spirituality. To achieve

a comfortable and familiar feel, he incorporated a parapet that rises

along the curved wall, symbolizing reaching for Father Sky; a timber column

that signifies the connection to Mother Earth; and a circular waiting

area signifying the kiva, a sacred ceremonial chamber. Where many health

facilities on reservations and in tribal communities are cold and devoid

of native cultural values, the Taos-Picuris Center connects to and is

a part of the natural world.

Among

Brown’s award-winning projects is the Taos-Picuris Pueblos Health

Center in Taos Pueblo, N.M. Urged by tribal leadership to create a facility

that “feels like home, yet provides the ultimate best in modern

health care,” Brown used natural materials and integrated symbolically

significant elements of earth, sky, hearth, and spirituality. To achieve

a comfortable and familiar feel, he incorporated a parapet that rises

along the curved wall, symbolizing reaching for Father Sky; a timber column

that signifies the connection to Mother Earth; and a circular waiting

area signifying the kiva, a sacred ceremonial chamber. Where many health

facilities on reservations and in tribal communities are cold and devoid

of native cultural values, the Taos-Picuris Center connects to and is

a part of the natural world.

Brown

also has received design awards for the Tohatchi Indian Health Center,

Navajo, Tohatchi, N.M. Designed in the form of the hogan, an eight-sided

structure common to Navajo culture, the Tohatchi Indian Health Center

incorporates elements representative of Navajo crafts and tradition. In

deference to Navajo belief, the building faces east to receive the new

day’s warmth and blessings. Brown also has worked with other tribes

to enhance and modernize the housing of Native Americans. Collaborating

closely with tribal leaders throughout the Western states, Brown consistently

has used his aesthetic talents and design sensitivity to uplift the built

environment and improve the lives of some of the poorest and most neglected

people in this country.

Brown

also has received design awards for the Tohatchi Indian Health Center,

Navajo, Tohatchi, N.M. Designed in the form of the hogan, an eight-sided

structure common to Navajo culture, the Tohatchi Indian Health Center

incorporates elements representative of Navajo crafts and tradition. In

deference to Navajo belief, the building faces east to receive the new

day’s warmth and blessings. Brown also has worked with other tribes

to enhance and modernize the housing of Native Americans. Collaborating

closely with tribal leaders throughout the Western states, Brown consistently

has used his aesthetic talents and design sensitivity to uplift the built

environment and improve the lives of some of the poorest and most neglected

people in this country.

In discussing his award, Brown commented that, unlike many design awards, the Whitney M. Young Jr. Award “really looks out to the disadvantaged and poor” and “motivates young people to see that there are other ways to practice than in mainstream architecture.” His work consistently has shown that it is possible to be culturally sensitive and still build great projects. Brown clearly has met Whitney Young’s challenge to this profession to become involved in creating a better world.

Copyright 2004 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

| The AIA will present Brown with the Whitney M. Young Jr. Award at the AIA National Convention in Chicago in June. Read Whitney Young’s speech to the 1968 AIA convention.

|

||