New Aviation Museum Takes

Flight

Check out HOK’s design on your next Dulles

layover

by Tracy Ostroff

Marking the 100th anniversary of the advent of flight, the Smithsonian Institution on December 11 dedicated the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Va., a companion facility to the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., for display and preservation of the museum’s collection of large historic aviation and space artifacts. The HOK-designed complex, the nation’s largest and most comprehensive aviation and space museum, occupies a series of hangars on a 176.5-acre site a few miles from the main terminal at Washington Dulles International Airport. The facility houses some of the nation’s most cherished aviation and space artifacts, including the SR-71 Blackbird, the fastest airplane ever built; the Air France Concorde (the first Concorde acquired by an American museum); the B-29 Enola Gay; and the space shuttle Enterprise.

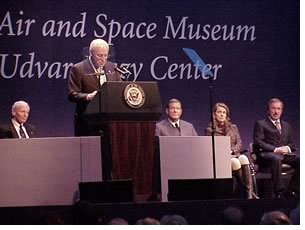

Vice

President Dick Cheney noted at the dedication ceremony that the building

is “longer end-to-end than the entire first flight of the Wright

Brothers.” Cheney, who is also a Smithsonian regent, said, “The

American people rightly associate the Smithsonian Institution with high

standards of historic preservation and superb presentation. Those standards

are apparent throughout the nearly 300,000 square feet of this structure.”

Vice

President Dick Cheney noted at the dedication ceremony that the building

is “longer end-to-end than the entire first flight of the Wright

Brothers.” Cheney, who is also a Smithsonian regent, said, “The

American people rightly associate the Smithsonian Institution with high

standards of historic preservation and superb presentation. Those standards

are apparent throughout the nearly 300,000 square feet of this structure.”

A host of politicians, aviation pioneers, and flying enthusiasts praised the facility before Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist officially dedicated it. Even John Travolta, the actor with his own 707, who was on site to introduce aviation heroes including John Glenn and Neil Armstrong, was moved by the facility and the history it exudes.

Flying

formations

Flying

formations

At 103-feet by 986-feet by 248-feet, the main aviation hall in large enough

to hold the entire original Air and Space Museum, also designed by HOK.

The architects and curatorial staff beautifully filled the series of hangars

with three levels of aircraft: two suspended from moveable steel trusses

and a third on the floor.

William Jacobs, head of the museum’s curatorial team, used a computer program to precisely measure the suspension wires within a quarter-inch. “Most planes are hung with three guy-wires, two for holding the weight and one for stability,” says Bill Hellmuth, AIA, senior principal and director of design at HOK’s Washington, D.C., office. “There’s this great curving truss, so the top point of that truss is a moving target.” Jacobs suspended the planes in their traditional flight maneuvers. “Jacobs decides whether the plane is going to be banking to the left or flying upside down, as is the case in the front-entry gallery,” Hellmuth says. "Without that kind of precision it would be difficult to hang the collection.”

The result is that visitors can enjoy novel views of the planes from ground level, or upside down and sideways from the elevated walkways that run parallel to the two tiers of suspended aircraft. Guests can mosey up to the fastest airplane ever built or come nose-to-nose with an aerobatic championship aircraft. Ultimately, the Udvar-Hazy Center will house more than 200 aircraft and 135 large space artifacts, about 80 percent of the national collection, the museum reports. Many will be displayed for the first time and will be accompanied by adjacent, free-standing exhibit stations that illuminate the artifact’s place in the history of flight.

Preparing

for takeoff

Preparing

for takeoff

Early on, the planners looked at the Air and Space Museum’s demographics

and found that visitors tend to be multi-generational. “Very often

you will have grandparents, parents, and children on the same trip,”

says Hellmuth. “We wanted to design the facility in such a way that

there would be a short tour, which could be experienced in a certain period

of time, and then a long tour, where people could spend all day at the

facility.”

Hellmuth describes the inside: “When you enter the museum, the first place that you land is a fuselage-shaped space, which has a sloping clerestory. That’s a large space where people can assemble. Busloads of school children, for example, can get off the bus at this point and get oriented. Then you walk through that space and you end up at this overlook point where you’re staring down into the cockpit of the SR-71. Then you see the whole large room and the space hangar behind, and you see the nose of the space shuttle peeking out at you. It sets up this very straightforward cross-axis, and everyone understands exactly where they are.

“In the distance to your left, you’ll also see this great spiral tower and elevator that takes you up to the high mezzanine, which is sort of irresistible for kids and fun for adults. You come down the ramp and work through the main exhibit hangar, working your way over to the stairs. You wind your way up, and you’re walking along the high mezzanine, which is suspended on wires. Like flight itself it’s this wonderful sensation; you don’t know why it works but you know it’s perfectly safe.” The walkway circles back and takes you into the space hangar and then eventually that route will go through the restoration hangar and then back out. At every point along the way there are breakout points and stairs down and elevators up, to rest or to visit a Discovery Station.

Connections

Connections

“One of the things that was very important to us is that this facility

is at an airport,” Hellmuth says, and they worked to put the design

elements in that context. “When you drive up, for example, the entry

level is 15 feet above the parking level, very much like the departures

level of a terminal would be, allowing the whole set up of walking in

through the fuselage and being slightly above the SR-71 Blackbird that

is so magnificent in plan . . . The outside program is both a reflection

of Eero Saarinen’s original design for Dulles and a nod to the 21

Zeppelin hangars that were built on the East and West coasts before World

War II.”

Sophisticated environmental controls, Hellmuth says, are key to the center’s success as a learning and restoration facility. “When we designed the original Air and Space Museum—and most aviation museums that followed it followed the same path—we had huge amounts of glass so that you could look at the artifacts against the sky.” But while that approach can yield dramatic and wonderful results, a drawback is that the level of natural light can degrade the artifacts. Huge amounts of glass just were not in the cards here, because this is a display storage facility. To preserve some reflected daylight, the architects included a series of light shelves.

Looking

ahead

Looking

ahead

The facility opens with 81 aircraft, but plans on the horizon would add

a restoration hangar, where visitors will have a window on the workers

who are rehabilitating the nation’s air and space treasures. Federal

funds were allocated for the initial planning and design, but the museum

needs to raise $90 million to build the second phase and pay off all outstanding

notes for the project.

Hellmuth says his favorite aspects of the building are the notion of its power of scale, and the ways the people interact with the building and the building interacts with the artifacts. The two Air and Space Museums will be connected by a shuttle that will bridge the 28-mile distance between them but will also retain their own identity. “The museum on the Mall is the beautiful stone museum whose design remains fresh and crisp today. This is a very different kind of facility that is all about engineering and technology and being in an airport. It is a more straightforward approach, expressing those technologies that make the building work, as opposed to covering them over with materials. It’s really sort of showing and displaying all the pieces of the building that allow it to be put together.”

Copyright 2003 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

|

||

| Hensel Phillips Construction Co. served as the project contractor. Explore the National Air and Space

Museum Web site.

|

||