Three Approaches for Introducing Architecture to Young People

To give students interested in design and architecture an opportunity to demonstrate their skills and creativity, a California architect has organized a design competition open to all high-school students in Santa Barbara County. Further east, a Colorado architect is helping to develop Web-based educational resources for grades K–12 that teach critical concepts through a focus on architecture. And a practitioner and professor in Washington, D.C., found his bliss introducing elementary-school students to the built environment. These three architects are all introducing their trade to children with the idea that the youngsters, through architecture, can find new ways to learn, solve problems, and view and appreciate their environment.

Design Competition for High School Students: David Goldstien, AIA

For

the past 13 years, David Goldstien, AIA, of Solvang, Cailf., has challenged

Santa Barbara County high-school students with a range of design programs

during a two-stage design competition, including a youth hostel, senior-citizen

housing, a beach house, a cabin in the woods, the design of a home for

Habitat for Humanity, and, most recently, a university research center

in California’s Mojave Desert.

For

the past 13 years, David Goldstien, AIA, of Solvang, Cailf., has challenged

Santa Barbara County high-school students with a range of design programs

during a two-stage design competition, including a youth hostel, senior-citizen

housing, a beach house, a cabin in the woods, the design of a home for

Habitat for Humanity, and, most recently, a university research center

in California’s Mojave Desert.

Participation in each year’s event averages between 65 and 75 students who spend an entire day engaged in a design charrette at a centrally located high school. Working at long banquet tables with three students per table, they are given a design program and about seven hours in which to complete their design and required drawings: plot plan, floor plan, elevation, and one additional view of their choice. All work is completed by hand, with t-squares, pencils, and other tools. At one time Goldstien was responsible for raising funds for the program. Now the local Rotary Club provides funding.

Immediately

following the charrette and after students depart, local architects score

each entry numerically, awarding up to 50 points on the solution of the

problem, up to 30 for creativity, and up to 20 points for clarity of presentation.

The 12 top-scoring students become finalists and present their designs

before a jury of four architects and architecture educators the following

week. During the juried review, the finalists make brief presentations.

The judges then discuss their design decisions, offer possible alternative

solutions, and engage in one-on-one interaction with each student. Each

project is then scored numerically, based on the same criteria as the

charrette. At the conclusion of the morning’s review, scores are

tabulated and, following a luncheon for all students and guests, awards

(including cash prizes) are distributed.

Immediately

following the charrette and after students depart, local architects score

each entry numerically, awarding up to 50 points on the solution of the

problem, up to 30 for creativity, and up to 20 points for clarity of presentation.

The 12 top-scoring students become finalists and present their designs

before a jury of four architects and architecture educators the following

week. During the juried review, the finalists make brief presentations.

The judges then discuss their design decisions, offer possible alternative

solutions, and engage in one-on-one interaction with each student. Each

project is then scored numerically, based on the same criteria as the

charrette. At the conclusion of the morning’s review, scores are

tabulated and, following a luncheon for all students and guests, awards

(including cash prizes) are distributed.

Goldstien says about 15 percent of last year’s entrants were females, as were three of the five top prizewinners. He reports that the first prizewinner has gone on to a summer program in architecture and looks forward to studying the subject once she graduates.

Goldstien

says he thought of starting the competition program when his children

were in high school competing in various contests in other areas, such

as dance, writing, and music. He says he wanted to provide an opportunity

for students to try out their drawing and design skills, too. Many of

the contest participants are culled from the district’s drafting

classes in the high schools’ occupational tracks. He says he is

trying to widen participation to other public- and private-school students

and link the competition to a more formal introduction to architecture

education. Right now, prior to the competition, he provides the participating

schools with information about past projects and copies of previous winning

entries and has given some crash courses in architecture at his office.

Goldstien

says he thought of starting the competition program when his children

were in high school competing in various contests in other areas, such

as dance, writing, and music. He says he wanted to provide an opportunity

for students to try out their drawing and design skills, too. Many of

the contest participants are culled from the district’s drafting

classes in the high schools’ occupational tracks. He says he is

trying to widen participation to other public- and private-school students

and link the competition to a more formal introduction to architecture

education. Right now, prior to the competition, he provides the participating

schools with information about past projects and copies of previous winning

entries and has given some crash courses in architecture at his office.

“This event has been successful largely because of the enthusiasm of high school instructors,” Goldstien concludes. “Over the years, they have recognized the values to students of ‘jumping in with both feet’ to tackle a design problem, as well as the experience of interacting with design professionals on an individual basis.”

Architecture-based curriculum in Colorado: Stephen George, AIA

In October 2001, Stephen George, AIA, a principal of Davis George Architects, Denver, founded CONNECT, a nonprofit organization to develop “StudioK12,” a collection of Web-based educational resources for grades K–12 that focus on architecture. With architect Ted Schultz, AIA, principal at Agency for Architecture, and Suzi Juarez, a member of the Jefferson County Schools board of directors, George envisions a program that will incorporate “virtual architecture field trips” and “architecture correspondent expeditions” that will explore the profession of architecture, architecturally significant cities worldwide, works of master architects, and specific building types. George notes that each field trip and expedition will incorporate a “teacher’s briefcase” developed by architects and educators that provides instructors with lesson plans, quizzes, and tests for easy integration of the programs within the different school curricula.

George envisions that the first CONNECT StudioK12-Colorado Projects would focus on the Denver Art Museum expansion. George and his colleagues have contacted the museum about setting up a four-part multimedia program that documents the process of design and construction of the museum's expansion while exposing children to the various people and organizations that make such a project a reality. The program would be led by teams of correspondents—architects from across the state—who would visit classrooms to introduce children to the program and establish a personal connection. Each part of the series would include video documentation, links to online resources, live Web casts, multidisciplinary educational curriculum within the teacher's briefcase, and interaction with the architectural correspondents via the Internet. Officials at the Denver Art Museum note that they are considering a variety of proposals, but look forward to learning more about George's program.

“The best career in the world”: David R. Dibner, FAIA

“I

would like to share with you a wonderful happening I just experienced,”

writes David R. Dibner, FAIA. “In response to a notice calling for

architects to combine their skills with local grade school teachers, I

volunteered my services to the Washington Architectural Foundation . .

. I had no idea about what I would encounter teaching in a local grade

school. However, the time requirement was minimal, and I was curious.”

“I

would like to share with you a wonderful happening I just experienced,”

writes David R. Dibner, FAIA. “In response to a notice calling for

architects to combine their skills with local grade school teachers, I

volunteered my services to the Washington Architectural Foundation . .

. I had no idea about what I would encounter teaching in a local grade

school. However, the time requirement was minimal, and I was curious.”

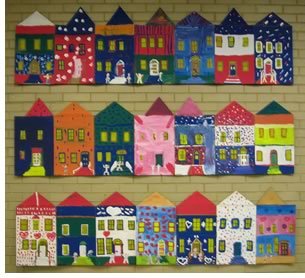

A delightful experience ensued, Dibner reports. An art teacher at an elementary school in Arlington, Va., a Washington, D.C., suburb, identified 14 fourth- and fifth-grade students who expressed an interest in architecture. The group would meet for 1-1/2-hour sessions once a week after school for eight weeks. The curriculum was open, but the end result would be a public display of the students’ work in a library in Washington, D.C.

“We

decided that our approach would be to have the students become more sensitive

to their environment and learn the basic fundamentals of how architects

approach the design of a project. The 10-year-old boys and girls were

given nametags with the title ‘Junior Architect.’ They were

given sketchbooks and assigned homework between classes in which they

would record elements they had noticed in their built environment. They

would then discuss what they had seen in class. Using their school and

neighborhood, they also learned about materials, structural systems, and

the many things that must go into the design of a building. It was amazing

how quickly their awareness of their environment improved.

“We

decided that our approach would be to have the students become more sensitive

to their environment and learn the basic fundamentals of how architects

approach the design of a project. The 10-year-old boys and girls were

given nametags with the title ‘Junior Architect.’ They were

given sketchbooks and assigned homework between classes in which they

would record elements they had noticed in their built environment. They

would then discuss what they had seen in class. Using their school and

neighborhood, they also learned about materials, structural systems, and

the many things that must go into the design of a building. It was amazing

how quickly their awareness of their environment improved.

“The main challenge was then to act as an architect. They would design their own home. Their first step was to interview their family to discuss their requirements. We then discussed how to develop adjacencies, space requirements, etc. Their floor plans began to take shape, and one of the hardest lessons was to understand the three-dimensional relationships between floors. We then discussed the exterior of their homes. They had been asked to notice and record different types of materials, windows, doors, overhangs, etc., and we made available many pictures of exteriors. They learned about the relationship of their plans to the façade and drew up their front elevation.”

Dibner

concludes, “My main reason for writing is to say that this teaching

effort was a wonderful, fulfilling experience for me. It reminded me how

rewarding it is to work with young people and how much you can learn from

them. The icing on the cake was when I learned that one of our students

had written her essay for Career Day, which she entitled ‘The Best

Career in the World.’ It included the words, ‘I want to become

an architect because then you can provide shelter for people. You can

give people a place to live where they can be happy.’ How’s

that for an incentive to teach?”

Dibner

concludes, “My main reason for writing is to say that this teaching

effort was a wonderful, fulfilling experience for me. It reminded me how

rewarding it is to work with young people and how much you can learn from

them. The icing on the cake was when I learned that one of our students

had written her essay for Career Day, which she entitled ‘The Best

Career in the World.’ It included the words, ‘I want to become

an architect because then you can provide shelter for people. You can

give people a place to live where they can be happy.’ How’s

that for an incentive to teach?”

Copyright 2003 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

|

||

| David Goldstien, AIA, would like to know if other architects are working on similar projects, and especially if you have educational materials to share. He can be reached at 805-688-1530 or dga@silcom.com. Email CONNECT to receive information about membership and to learn more about the ways you can contribute to the organization. Live in the Washington, D.C., area? Check out the Washington Architectural Foundation’s Web site for volunteer opportunities.

|

||