Istanbul’s New Housing Trends: Caught Between Global and Local?

by

Associate Professor Dr. Ulku Altinoluk and Professor Dr. Hulya Turgut

by

Associate Professor Dr. Ulku Altinoluk and Professor Dr. Hulya Turgut

Yildiz Technical University Faculty of Architecture, Istanbul

Over the last two decades, Istanbul’s socio-cultural and urban identities have been transforming radically. Turkey’s globalization, internationalization, and rapid flow of information have played a significant role in changing this grand old city and her people. As in the rest of the world, the multidimensional outcomes of this transformation have manifested in peculiarities of activity patterns, behavioral relationships, and social and cultural norms, as well as architectural and urban patterns. This rapid economic and social change demands continual redefinition of urbanization and housing concerns. Especially for newly emerging urban areas, it is essential to define what a “good quality environment” means to users today.

Emerging

housing patterns

Emerging

housing patterns

Istanbul traditionally is described either as a bridge between East and

West, Islam and secularism, or an arena of strife between these. In reality,

the city is much more complex and

confusing than the clichés suggest. It is a place in which a struggle

for the spirit of the city and the identity of its residents has been

taking place. “Istanbulites” are insisting on an Istanbul

transformed by globalization. Consequently, the city has been developing

with intense heterogeneity, especially in its urban housing, as never

before.

The development patterns of Istanbul’s housing over the last 50 years can be divided into three periods.

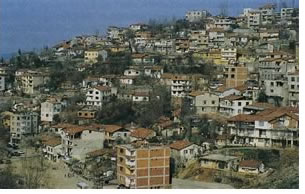

- Beginning with the 1950s, migration from rural to urban areas resulted in shantytowns surrounding the city center.

- From the end of the 1960s through the 1970s, differences in national development and in the housing areas of the middle class became apparent.

- Beginning in the 1980s, globalization and today’s current patterns of high-rise residences and luxury villas began to emerge.

Of course, one phase doesn’t end when the next begins. Shantytown developments still thrive, and the middle class continues to desert traditional housing for luxury villas and high-rises.

Globalization’s

high-rises and luxury villas

Globalization’s

high-rises and luxury villas

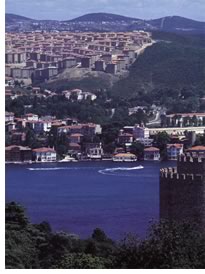

New spatial developments that appeared in Istanbul beginning in the 1980s

reflect the influence of globalization and its attendant flow of international

capital and intensified know-how. Under globalization’s spell, Istanbul

quickly created a society of new businesspeople and professionals. Well-educated

young men began working at high salaries in Turkish and foreign capital

companies. In addition, young women joined the speedily growing market,

and, for the first time, two-income couples entered the housing market.

Wanting to continue a lifestyle that fit their social level, this wealthy

new group—who had traveled to the global cities of the world—began

demanding luxury housing. The result has taken shape in the form of projects

housing 60,000 to 70,000 people, the majority of whom work for the media,

as models and athletes, in international companies, and in the finance

sector or are foreigners.

Prior to the 1980s, luxury housing in Istanbul—bearing names containing the terms “Country” or “City”—was owned by the elite of Turkey’s business world, who lived in custom-designed mansions with gardens. Simultaneous to the rise of giant high-rises, interest arose in reviving old Istanbul’s local character. Entrepreneurs who became familiar with this interest now sell freestanding villas as “life in a local quarter.” Ads play up “contemporary lifestyle” luxury apartment flats and big villas constructed to international standards with imported materials. Key selling terms are “high security” and “ultra luxurious.” In a manner not unique to Istanbul, most of these units are at a distance from the center city. It is possible to live protected by security walls, far from urban filth, confusion, and noise. As a result, showy consumption has become linked with being spatially separate from Istanbul society.

This

separation has become a much-debated dimension of the new globalized order

in Turkey, as over the last 10 years these projects have rapidly sprung

up in areas that were empty fields or shantytowns. To offer their tenants

privilege and possession, apartment owners select only residents with

a certain income level and make their leases subject to the approval of

their neighbors. These new settlements have created a kind of “select

social club” community in which people can become members only with

a minimum of two positive references.

This

separation has become a much-debated dimension of the new globalized order

in Turkey, as over the last 10 years these projects have rapidly sprung

up in areas that were empty fields or shantytowns. To offer their tenants

privilege and possession, apartment owners select only residents with

a certain income level and make their leases subject to the approval of

their neighbors. These new settlements have created a kind of “select

social club” community in which people can become members only with

a minimum of two positive references.

Reality

check: What do users really want?

Reality

check: What do users really want?

Istanbul’s recent housing projects, representing new ways to organize

social and cultural differences, might be read as creating segregation

and producing housing inequalities while transforming the character of

public life in undesirable ways. Do users really want this kind of spatial

isolation? To know, it is necessary to pinpoint their objectives—physical,

social, environmental—and define a “good quality” environment

for urban housing. Creating quality living environments requires both

physical/objective and psychological/personal input. In conclusion, we

believe it is time to ask:

- What is quality of life? Is it a confused concept that supports different meanings given different environments and conditions?

- In the area of housing, is it possible to create a viable Turkish “country house,” or is that a contradiction in terms?

- What is a globalized life in this century? How should one live? What does this mean in terms of design quality?

- Can we return Istanbul to the Istanbulite?

Copyright 2003 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

| • Keyder, C. “Istanbul in Between the Global and the Local,” Metis, Istanbul (1999). • Marcuse, P., and R.Van Kempen, “Globalizing Cities: A New Spatial Order?” Blackwell, Oxford (2000). • Rapoport, A., “Theory, Culture and Housing” The Journal of Housing, Theory and Society, 2001;17:145-165 (2001). • Turgut, H., “Culture, Space and Urbanization/A Structural Analysis of the Housing Pattern in Squatter Settlements,” IAPS 15 Conference, Eindhoven, Holland, (July 1998). • Turgut, H., “Determination of Culture and Space Interaction in Squatter Settlements, Example: Pinar Settlement,” research project sponsored by ITU Research Fund, Istanbul. Istanbul Technical University, Faculty of Architecture (1996). • Turgut, H., and P. Kellett, “The Spaces of Home, An Examination of Domestic Space in Squatter Settlements,” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements working paper series, IASTE ,Vol.99, pp.85-108, Berkeley, Calif. (1996). • www.arkitera.com

|

||