Designing for the Stars

Cleveland’s new planetarium evokes

an astronomic instrument

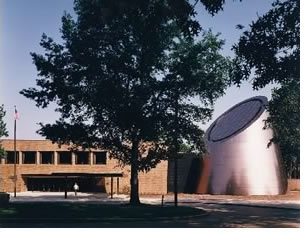

The

newest addition to the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, the Nathan

and Fannye Shafran Planetarium by van Dijk Westlake Reed Leskosky, suggests

a sleek, futuristic identity. A metal-clad, chamfered cone, this sculptural

addition angles toward and aligns with the North Star. The striking shape

and bronze color of the 60-foot-tall planetarium heralds the museum’s

current effort to transform itself through a series of modestly scaled

facilities. This museum in particular aims to appeal to school children

and repeat visitors through up-to-date technology, equipment, and live

programming.

The

newest addition to the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, the Nathan

and Fannye Shafran Planetarium by van Dijk Westlake Reed Leskosky, suggests

a sleek, futuristic identity. A metal-clad, chamfered cone, this sculptural

addition angles toward and aligns with the North Star. The striking shape

and bronze color of the 60-foot-tall planetarium heralds the museum’s

current effort to transform itself through a series of modestly scaled

facilities. This museum in particular aims to appeal to school children

and repeat visitors through up-to-date technology, equipment, and live

programming.

For this project, the architects asked themselves how to take a program that is “traditionally circular in shape, domical in section, and devoid of windows and transform it into memorable architecture.” They soon found their answer. “We accepted its geometry, but treated it as sculpture, shaping it as a chamfered cone angled toward the North Star and resonating with a bronze color metal skin. The planetarium functions as an astronomic instrument, imbued with iconic and educational meaning,” said Paul Westlake Jr., FAIA, principal of Cleveland-based architecture and engineering firm. The architects took further direction from the museum’s educational emphasis and the other cultural buildings that provide context for the planetarium, including the city’s botanical gardens, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and Western Reserve Historical Society.

Inspiration

from Polaris

Inspiration

from Polaris

At its highest point, the conical form is about as tall as it is wide

at the ground. The chamfer through the cone creates an elliptical cross-section

whose longitudinal axis is aligned at precisely 41.5 degrees, the viewing

angle to Polaris (the North Star) at Cleveland’s latitude. The architects

say this combination of angle and orientation will always place the North

Star hovering at the tip of the cone. Because all constellations appear

to rotate around Polaris, the exterior cone form and its orientation,

in effect, does function as an astronomic instrument. If the cone’s

titanium-nitride-sputtered, 14-gauge stainless steel plate brushed with

an angel-haired finish is reminiscent of finely machined brass and bronze

astronomic instruments, that was purposeful: the architects carefully

selected the material and color to obtain a finish and appearance that

would evoke traditional astronomical and viewing instruments. The architects

note that they chose the material because it will not discolor, patina,

chalk, or corrode overtime.

The

steel-frame structure is clad with cement board and covered with self-healing

waterproof membrane. “The metal skin system is complicated by the

fact that panels are trapezoidal in shape, yet their tops and bottoms

actually take the form of arcs, with the tops having a sharper radius,

explained Phillip Schroeder, AIA, a van Dijk Reed Leskosky associate.

“The panels must be cut to a specific shape, curved and applied

to the conical form so that the arcs appear as a straight line and horizontal

element when viewed.” Tom Tormey, a museum trustee and chairman

of the Building Grounds and Construction Committee, seconded these comments:

"This was an incredibly complex project, with no straight corners."

The

steel-frame structure is clad with cement board and covered with self-healing

waterproof membrane. “The metal skin system is complicated by the

fact that panels are trapezoidal in shape, yet their tops and bottoms

actually take the form of arcs, with the tops having a sharper radius,

explained Phillip Schroeder, AIA, a van Dijk Reed Leskosky associate.

“The panels must be cut to a specific shape, curved and applied

to the conical form so that the arcs appear as a straight line and horizontal

element when viewed.” Tom Tormey, a museum trustee and chairman

of the Building Grounds and Construction Committee, seconded these comments:

"This was an incredibly complex project, with no straight corners."

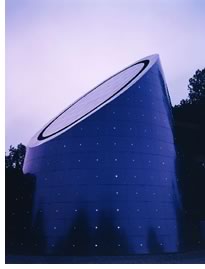

Fiber-optic lighting gives the planetarium a nighttime presence without casting a harsh light into the sky. “At night, it is articulated by a grid of points of light, ordering the heavens and set in geometric relationship with the stars. The result is a dialogue between the randomness of the lights in the sky and frozen grid of light,” Westlake said, referring to the 440 fiber-optic points that reveal the cone shape in the evening hours.

Interior

detail

Interior

detail

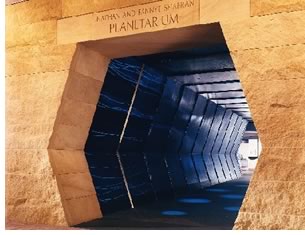

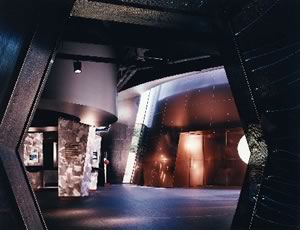

The entranceway is designed as a 50-foot connective tissue, linking the

cone form with the existing brick-clad building. The octagonal walls are

fashioned from perforated metal. Sound bites from past space flights transport

visitors from earth to space. Fiber-optic cables running the length of

the passageway create a random pattern, and in the astronomy exhibit hall,

the walls are painted a speckled black. Darkly tinted glass blocks light

from the exhibit hall, but still reveal the full form of the planetarium’s

cone from the perspective of the interior.

The

planetarium’s all-dome video projection system, the most advanced

of which projects more than 5,000 celestial images onto the 40-foot suspended

perforated aluminum dome, is surrounded by 86 auditorium seats. This,

along with the presenter’s seat, equals the number of constellations

in the sky. The set-up allows for personalized instruction to school children,

complemented by an interactive “hands-on” learning experience,

computerized exhibit hall, and the museum’s historical collection

of celestial objects.

The

planetarium’s all-dome video projection system, the most advanced

of which projects more than 5,000 celestial images onto the 40-foot suspended

perforated aluminum dome, is surrounded by 86 auditorium seats. This,

along with the presenter’s seat, equals the number of constellations

in the sky. The set-up allows for personalized instruction to school children,

complemented by an interactive “hands-on” learning experience,

computerized exhibit hall, and the museum’s historical collection

of celestial objects.

Project Director Amy Dibner, AIA, another van Dijk Westlake Reed Leskosky associate, acknowledged the effort and technical complexity involved in an innovative undertaking. “Because this project has been so exciting and innovative, everyone involved in it has felt passionate about it,” she said.

Copyright 2003 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

| Images © Nick Merrick, Hedrich Blessing

|

||