Every other year, representatives from the AIA and the American Library Association gather to select the finest examples of one of the building types most revered by the public: the library. The 2003 AIA/ALA Library Building Awards honor seven disparate projects, from a small, private research facility in the hills of Virginia to 325,000 square feet of renovation in three buildings at the University of Washington. All share successful resolution of their patrons’ needs into harmonious and beautiful designs.

And the winners are:

Lee

B. Philmon Branch Library, Riverdale, Ga., by Mack Scogin Merrill Elam

Architects, for the Clayton County Library System.

Lee

B. Philmon Branch Library, Riverdale, Ga., by Mack Scogin Merrill Elam

Architects, for the Clayton County Library System.

“Corralled by sprawling suburbia, the little library asserts

itself with quietude within a rapidly changing landscape,” reports

the architect. “Harnessing the mundane, the library invokes the

abstract and aspires to the sublime.” Its serenity within a sea

of neon and chain-store detailing makes its simple geometries and subtle

coloring all the more appealing. Inside, its 14,000 square feet offer

an “oasis of variegated space and light,” thanks to large

triangular expanses of wall and skylight fenestration. A barrel-shaped

public room on the south and outdoor reading garden on the north soften

the building’s angularity. (Photo © Timothy Hursley, The Arkansas

Office.)

The

Jefferson Library at Monticello, Charlottesville, Va., by Hartman-Cox

Architects, for the Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

The

Jefferson Library at Monticello, Charlottesville, Va., by Hartman-Cox

Architects, for the Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

Half a mile down the road from Thomas Jefferson’s beloved Monticello

sits a quiet and dignified Colonial Revival house designed by Delano and

Aldrich, now owned by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. The charge to the

architect was to create a 15,000-square-foot research library adjacent

to this house to serve its center and staff. “The design of the

new library reflects the angularity of the roofs, the rectangular planning

and crispness of the Delano and Aldridge House itself,” says Hartman-Cox

Architects, “while disguising the fact that it is three times as

large as the house by placing its bulk to the rear and down the hill.”

The new library contains a two-story reading room, offices, conference

room, a work area for research on the presidential papers, and a rare-book

storage area. (Photo © Robert Lautman.)

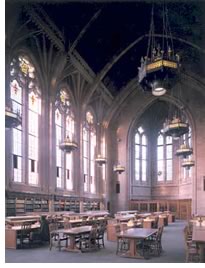

Suzzallo

Library, University of Washington, Seattle, by Mahlum Architects and associate

architect Cardwell Architects, for the University of Washington Libraries.

Suzzallo

Library, University of Washington, Seattle, by Mahlum Architects and associate

architect Cardwell Architects, for the University of Washington Libraries.

Driven by the need for seismic and accessibility upgrades, this project

entailed restoration of the complex’s 1925, 1935, and 1965 buildings—some

325,000 square feet on seven floors. The architects replaced the mechanical,

electrical, and conveyance systems; upgraded the communications system;

wrote the functional and technical programs; and prepared a feasibility

study to help the university raise money for the project. Much of the

interior was demolished to make way for new structural elements and building

systems, so the architects needed to take extra pains to preserve the

building’s historic features, notably the entry lobby, grand stair,

octagon, and reading room. In addition to the restoration itself, they

say their greatest challenge was to fit the library’s program into

the historic structure. (Photo © Benjamin Benschneider.)

Seattle

Public Temporary Central Library, Seattle, by LMN Architects, for the

Seattle Public Library.

Seattle

Public Temporary Central Library, Seattle, by LMN Architects, for the

Seattle Public Library.

Although less than half the size of the new Seattle Public Library under

construction, this temporary library has housed 600,000 volumes and provided

a full range of services during the 2-½ years of the new library’s

construction. Through the magic of LMN Architects, the temporary facility

is able to provide primary book distribution and computer service hubs

for the 23-branch system as well as administrative offices, children’s

library, computer training center, meeting rooms, and space for the 350-person

staff. Intense tropical colors contrast with the exposed structure and

mechanical systems, reinforcing what the architects term their “camping

metaphor: living in the woods with few amenities may not be ideal over

the long haul, but for a short, finite period, it can be fun and exciting.”

The three-level building shell, built to house a museum, will return to

its original function when the permanent library is complete. (Photo ©

Fred Housel.)

South

Court, New York Public Library, New York City, by Davis Brody Bond, LLP,

for the New York Public Library.

South

Court, New York Public Library, New York City, by Davis Brody Bond, LLP,

for the New York Public Library.

This project, a new, 42,500-square-foot, three-story structure, resides

in the open south courtyard of the New York Public Library, a national

landmark building. The new $29 million building accommodates the library’s

public education program as well as administrative/staff support, plus

an electronic teaching center, auditorium, administrative offices, and

an employee lounge located on the glass-walled top floor. The original

building, completed in 1911, has earned its place as a remarkable and

historically significant New York City structure. In designing a new building

within this space, the architect acknowledged the importance of creating

a modern structure respectful of its historic Beaux Arts elder, yet one

that offers an important contemporary addition to the institution itself.

Consequently, the new structure contains a level of detail comparable

to that of the original. Skylights adorn the entire structure, while the

floor, set back from the existing stone walls of the courtyard, reveals

the façade to the public for the first time. The original foundation

walls are exposed at the bottom of a glass staircase, which descends from

the first floor to the auditorium. The upper floors are cantilevered,

held back from the original walls by glass partitions, thus adding to

the feeling of transparency. (Photo © Peter Aaron/ESTO.)

The

Hockaday School Upper and Lower School Library, Dallas, by Overland Partners

Architects with Associate Architect Good Fulton + Farrell, for the Hockaday

School.

The

Hockaday School Upper and Lower School Library, Dallas, by Overland Partners

Architects with Associate Architect Good Fulton + Farrell, for the Hockaday

School.

This new library serves as the centerpiece of a multi-million dollar renovation

and new construction project for a prestigious all-girls academy in Dallas.

In addition to space for 40,000 volumes, Overland Partners Architects

and their associate architect, Good Fulton + Farrell, designed the new

structure to house state-of-the-art computer resources, a multimedia boardroom,

audiovisual center, and conference center. Sited at the heart of the campus,

the new library offers easy access from both the lower and upper schools.

Its orientation takes maximum advantage of natural light and permits preservation

of three large oak trees in the center of the campus. Respectful in appearance—via

brick, stone, and glass components—to the 1950s Modernist campus,

the building expresses its individuality through an elliptical form. (Photo

© Craig D. Blackmon, AIA.)

Shady

Hill School Library, Cambridge, Mass., by Kennedy and Violich Architecture

Ltd., for the Shady Hill School.

Shady

Hill School Library, Cambridge, Mass., by Kennedy and Violich Architecture

Ltd., for the Shady Hill School.

Renovation of this existing 8,000-square-foot elementary-school library

required the Kennedy and Violich Architecture firm to “integrate

digital learning tools with the physical intimacy of books and reading.

The space also needed to house construction and display of art projects,

storytelling, music and video centers, tutorial rooms, and computer laboratories.

A raised-floor plenum accommodates the infrastructure that brings power

and data for use of the Internet and the school’s intranet. The

raised floor also helps define the project’s “Digital Platform,”

a ramped loft space that further defines the library’s activities.

The edges of the platform combine adjustable bookshelves and digital learning

tools, including flat screens, data ports, and workstations. “The

Digital Platform is clad with durable recycled paper and wood products

that were shop-built off site,” the architects report. “These

affordable materials are reminders of the natural origins of paper and

the relationships between books and technology. (Photo © Bruce T.

Martin & Photography.)

Copyright 2003 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

|

|

||