Panel discusses merit, execution of revenue proposals

From hard data provided by economists, revenue administrators, and policy watchers, to anecdotal evidence from the front lines of component executives and AIA members, it appears clear that financially struggling states are already implementing taxes on architecture and design services or may turn to these taxes soon in an attempt to make up their severe budget shortfalls. The AIA Grassroots Leadership Conference’s Government Affairs Day, May 9, continued to bring attention to ballooning state deficits and the drastic measures states are taking to balance their budgets.

Peter Harkness, editor and publisher of Governing magazine, was the first in the program to detail the fiscal troubles 46 of the 50 states recently have encountered as they faced increasing costs, particularly in education and health care. At the same time, they face declining revenues. In fact, 40 of 50 states reported revenue drops from 2002 levels. To shrink the gap, states are resorting to taxes on services, and any group that does not have an organized lobby to fight the measures is “dead meat,” Harkness said.

Aligning

tax systems

Aligning

tax systems

Later in the day, Harley Duncan, president of the Federation of Tax Administrators,

offered Grassroots attendees an expert’s assessment of sales taxation.

Addressing the topic “Catching Up—Aligning Tax Systems and

the 21st Century Economy,” Duncan placed the immediate tax challenges

in a broader context.

Our current tax system, Duncan said, is “not organized for a knowledge, information, and service-based economy.” Instead, he explained, today’s tax system is based on a 1930s structure exemplifying older economic values of taxing manufacturing, retail, and tangible personal property. Now that services account for 60 percent of the gross domestic product, he argued, it’s time to implement a more effective tax code that treats our economy equitably.

The system’s facets, such as taxes on property, corporate income, and retail have not kept up with today’s economic realities. For example, the retail sales tax is not equipped to tax non-tangible assets unless they are specifically included in the tax code. The role of the corporate income tax has declined by one-third in 10 years, and the ratio of intangible to tangible assets has increased 15-fold in 20 years.

Duncan concluded that this “structure has created a burden that falls unevenly across taxpayers and sectors” and has distortions that “continually erode the long-term capacity” of the tax because the disparities spiral and become greater at each revenue cycle. He said the “long-term erosion” must be offset by a “real” increase in revenues and by fixing the tax base so it more accurately reflects our economy.

Right now, only three states generally tax service transactions, and fewer than 50 percent extensively tax services, usually utilities, admissions, and labor. To catch up with their revenue needs, states are examining personal, business, and professional services. For truly fair implementation, Duncan advocated taxing all retail “once on the final stage of consumption.” He said this would promote neutrality and reduce tax pyramiding, which hits the consumer and service provider at several different points of purchase. Administration issues include “defining services appropriately, dealing with pyramiding, and the use of tax on interstate services,” which would be characterized as Tennessee consumers purchasing architecture services from an architect in Kentucky and not having to pay taxes. Fairness, therefore, would mean that that rules must be worked to taxing the service where it is used to avoid disadvantaging the in-state provider.

Panel:

Taxes are a reality

Panel:

Taxes are a reality

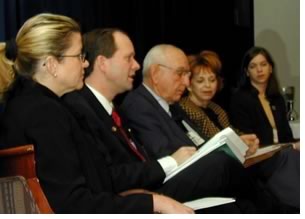

Following Duncan’s assessment, AIA national Government Affairs State

and Local Program Director Christy Agner convened a panel that brought

together professionals with diverse perspectives on service taxes. It

included:

• The Honorable Christopher R. Widener, FAIA, Widener-Posey Architects,

a member of the Ohio House of Representatives

• Connie Wallace, Hon. AIA, CAE, executive vice president, AIA Tennessee

• Charles J. Zwick, retired chair, Southeast Banking Corporation;

former chair, Florida State Comprehensive Plan Commission; and director

of the Office of Management and Budget under President Lyndon Johnson

• Patricia Myler, AIA, senior associate, Fletcher-Thompson, Inc.

Agner kicked off the panel discussion by noting that 25 states have discussed new taxes on professional services. Opinions on the merit of a tax on professional services varied. Zwick, for example, helped advocate and implement a professional services tax in Florida, while Wallace and her colleagues in Tennessee successfully fought a similar measure to the bitter end. But the panelists agreed that if architects want to oppose the tax, they must align with allied professional groups and business organizations, lobby their legislatures, and do their homework in advance of the advent of detrimental proposals.

As a practical matter, they also echoed Duncan’s assertion that, to ensure equity, all professions should be included in the tax.

Be the “squeaky wheel”

Widener, however, said it’s important to lobby on the profession’s

behalf, particularly because of the amount of revenue—$450 billion—that’s

involved in taxing architecture and engineering services. Widener also

said it is best to do the legwork before legislation is officially introduced.

The representative suggested communicating with key players crafting the

proposal, such as the tax commissioner, government fiscal officers, and

ways and means committees, because they have the ear of the governor.

He suggested educating these officials about how complicated it is to

tax services, arguing that architecture services are mobile, meaning that

firms in Cincinnati can open an office across the border in Kentucky.

Advocating the importance of having a proactive lobby, Widener said that it is important to be a “squeaky wheel” because the legislators will go after the “low-hanging fruit,” meaning an easy target. AIA Tennessee’s Wallace said the component asked its members to analyze the tax’s impact before the legislature began deliberations. They had determined that the gross sales tax would be the worst scenario and could bring that knowledge to the table when they fought a legislative proposal in 2002.

Wallace also said it is imperative to “find advocates among legislators.” She said these relationships have been a two-way street, with the lawmaker calling her to alert the component to adverse legislation buried in an obscure bill. She also issued a “call to activism” and asked architects to give back to their profession and community by running for elected office.

Notes from the field

Agner reminded the audience that professional-service taxes can appear

in a variety of forms: gross receipts tax, occupation tax, or a single-business

tax. She also said states can elect to defeat a tax but increase professional

service fees or implement a general business licensing fee.

Myler discussed Connecticut architects’ work in the late 1980s and early 1990s to defeat an 8 percent tax on building, planning, and design services. In response to the levy passed in 1989, the groups affected by the provision—architects, engineers, landscape architects, and surveyors—hired a lobbyist. In 1990, there were “a few pieces of legislation but no action,” she said. In 1991, however, the legislature repealed the tax. Myler attributed the success to a number of factors, including breakfast sessions with legislators that helped ensure their concerns were heard.

The tax eventually was repealed, she said, because of a confluence of

conditions, including:

• Lack of clarity in the legislation

• Lack of understanding of an architecture contract and the possibility

of double taxation because of the way firms hire contractors

• No remedy for getting reimbursed for the tax if the client did

not eventually pay the fee

• Transference of revenue to out-of-state firms.

Tennessee fought back a similar measure because they banded together with other business and professional organizations. They also were able to use the “border cities argument,” saying that a tax on professional services would drive business to neighboring states.

Finally, Widener suggested, “When something bad is going to happen,

make sure you get something back.” For example, he suggested that

architects ask for vendor fees to cover the cost of collecting the service

tax.

Copyright 2003 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

| Harley Duncan, president of the Federation of Tax Administrators, offered Grassroots attendees an expert’s assessment of sales taxation. (Photo by Douglas E. Gordon, Hon. AIA) Services tax panel (left to right): Patricia Myler, AIA; Christopher R. Widener, FAIA; Charles J. Zwick; Connie Wallace, Hon. AIA; and moderator Christy Agner. (Photo by Douglas E. Gordon, Hon. AIA)

|

||