A federal courthouse on Long Island, two innovative school designs in California, several buildings on college campuses, and a public library in Boston contribute to the awesome architecture collection that makes up this year’s 2003 AIA Honor Awards for Architecture. They telescope in size, from a small house in Nova Scotia to a refurbishment of the Big Apple’s Lever House, and in function, from a snow removal machinery barn to a primary school. Eleven of the projects are in the U.S. The other four are in Canada, France, Sweden, and Austria. New York was this year’s home to the most projects, topping the list with five.

ColoradoCourt, Santa Monica, by Pugh Scarpa Kodama, for Community Corporation of Santa Monica. Photo © Marvin Rand.

In

collaboration with the Community Corporation of Santa Monica, the City

of Santa Monica, and a team of expert consultants, the architects developed

ColoradoCourt as a model for sustainable living that exceeds conventional

standards and practices. The project includes 44 single-resident occupancy

units, a community room, mail room, outdoor common courtyard spaces, bike

storage, and a covered parking area for 20 cars. It is one of the first

buildings in the U.S. that is 100 percent energy neutral: ColoradoCourt

incorporates energy-efficient measures that exceed standard practice,

optimize building performance, and ensure reduced energy use during all

phases of construction and occupancy. ColoradoCourt brings award-winning

design to the affordable housing market, which has just begun to explore

the potential for fully integrated solutions through which quality design,

environmental and social responsibility, economic success, and urban development

can synergistically intermingle. “This is a serious attempt to test

the limits of sustainable technology and architecture; it should serve

as a model for future developments,” remarked the jury. “The

photovoltaic panels, rainwater collection, and shading systems all are

used to aesthetic advantage as integral parts of the architectural composition.”

In

collaboration with the Community Corporation of Santa Monica, the City

of Santa Monica, and a team of expert consultants, the architects developed

ColoradoCourt as a model for sustainable living that exceeds conventional

standards and practices. The project includes 44 single-resident occupancy

units, a community room, mail room, outdoor common courtyard spaces, bike

storage, and a covered parking area for 20 cars. It is one of the first

buildings in the U.S. that is 100 percent energy neutral: ColoradoCourt

incorporates energy-efficient measures that exceed standard practice,

optimize building performance, and ensure reduced energy use during all

phases of construction and occupancy. ColoradoCourt brings award-winning

design to the affordable housing market, which has just begun to explore

the potential for fully integrated solutions through which quality design,

environmental and social responsibility, economic success, and urban development

can synergistically intermingle. “This is a serious attempt to test

the limits of sustainable technology and architecture; it should serve

as a model for future developments,” remarked the jury. “The

photovoltaic panels, rainwater collection, and shading systems all are

used to aesthetic advantage as integral parts of the architectural composition.”

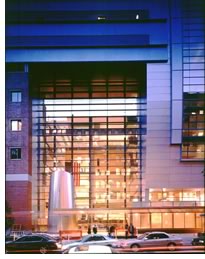

New Academic Complex, Baruch College, New York City, by Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates PC with Associate Architect Castro-Blanco Piscioneri, for the Dormitory Authority of New York. Photo © Michael Moran.

This

academic building occupies three-quarters of a full block on Lexington

Avenue in Lower Manhattan. Located in the center of Baruch College’s

new urban campus, the building sits squarely opposite the recently completed

Newman Library. The new building’s heart is a great central room

that steps towards the sun from north to south, offering a vertical interpretation

of the traditional college quadrangle. The transformed “quad”

connects three dominant pieces of the building: the business school, liberal

arts college, and their shared social amenities. The space functions as

a central gathering room where students and faculty can interact. Upper

floors, linked by the common atrium, accommodate a variety of classrooms

and offices. The lower floors house large public assembly spaces and athletic

facilities. An alternate setback at East 25th Street creates a linear

plaza, forming a public seam between the new building and the existing

Newman Library to the north. “The complex is an interesting concept

of space and shape in a rectangular world,” commented the jury.

They also liked the project’s slight modifications to form that

attract attention and use of natural light to enhance the interior.

This

academic building occupies three-quarters of a full block on Lexington

Avenue in Lower Manhattan. Located in the center of Baruch College’s

new urban campus, the building sits squarely opposite the recently completed

Newman Library. The new building’s heart is a great central room

that steps towards the sun from north to south, offering a vertical interpretation

of the traditional college quadrangle. The transformed “quad”

connects three dominant pieces of the building: the business school, liberal

arts college, and their shared social amenities. The space functions as

a central gathering room where students and faculty can interact. Upper

floors, linked by the common atrium, accommodate a variety of classrooms

and offices. The lower floors house large public assembly spaces and athletic

facilities. An alternate setback at East 25th Street creates a linear

plaza, forming a public seam between the new building and the existing

Newman Library to the north. “The complex is an interesting concept

of space and shape in a rectangular world,” commented the jury.

They also liked the project’s slight modifications to form that

attract attention and use of natural light to enhance the interior.

Federal Building and United States Courthouse, Central Islip, N.Y., by Richard Meier & Partners, Architects, with Technical Architect The Spector Group, for the General Services Administration. Photo © Scott Frances/ESTO.

“The

classic Modernist articulation of this building creates a proud and regal

form without relying on old emblems of the archetypal courthouse,”

said the jury of this new federal building. “The arrangement also

allows for the social ideology and the public nature of our system of

law to be expressed in built form.” Located in Central Islip on

Long Island, the Courthouse takes advantage of extraordinary panoramic

views to the Great South Bay and Atlantic Ocean beyond. The building rests

on a raised plaza that functions as a “place delineator,”

marking the bounds of the building and inviting occupation by means of

low walls and stairs. A conical, top-lighted rotunda serves as a plaza

focal point and marks the nine-story-high entry. Once inside, visitors

pass through security screening to a 12-story atrium in the main block,

which serves as the building’s orienting point and divides the district

court functions to the west from the bankruptcy court functions to the

east. The plaza façade, a gently flexed glass wall with projecting

sunscreens, admits generous light to the public corridors, allows uninterrupted

views of the bay, and provides a tensile backdrop for the entry rotunda.

The main rectangular volume, which contains the complex’s administrative

and judicial services and courtrooms, provides enough spatial flexibility

to accommodate expansion through a projected 30-year period.

“The

classic Modernist articulation of this building creates a proud and regal

form without relying on old emblems of the archetypal courthouse,”

said the jury of this new federal building. “The arrangement also

allows for the social ideology and the public nature of our system of

law to be expressed in built form.” Located in Central Islip on

Long Island, the Courthouse takes advantage of extraordinary panoramic

views to the Great South Bay and Atlantic Ocean beyond. The building rests

on a raised plaza that functions as a “place delineator,”

marking the bounds of the building and inviting occupation by means of

low walls and stairs. A conical, top-lighted rotunda serves as a plaza

focal point and marks the nine-story-high entry. Once inside, visitors

pass through security screening to a 12-story atrium in the main block,

which serves as the building’s orienting point and divides the district

court functions to the west from the bankruptcy court functions to the

east. The plaza façade, a gently flexed glass wall with projecting

sunscreens, admits generous light to the public corridors, allows uninterrupted

views of the bay, and provides a tensile backdrop for the entry rotunda.

The main rectangular volume, which contains the complex’s administrative

and judicial services and courtrooms, provides enough spatial flexibility

to accommodate expansion through a projected 30-year period.

Simmons Hall, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Mass., by Steven Holl Architects with Associate Architect Perry Dean Rogers & Partners, for MIT Department of Facilities. Photo courtesy of the architects.

The

architects envisioned this 350-bed residence as part of both the city

and campus form, calling it “a vertical slice of a city, 10 stories

tall and 330 feet long.” It provides amenities to students within

the dormitory that include a 125-seat theater and a night café.

House dining, at street level, looks and functions like a street-front

restaurant, replete with a distinctive awning and outdoor tables. Corridors

connecting the rooms are conceived of as streets inviting urban experiences.

Each of the dormitory’s single rooms has nine operable windows two-by-two-feet

in size. The 18-inch depth of the wall naturally shades out the summer

sun while allowing in the warmth and light of the low-angled winter sun.

Within the deep wall setting, color on the heads and jambs of the numerous

windows creates an identity for each of the 10 “houses” within

the overall building, and lighting at night from the nine-window rooms

is magical and exciting. The jury called the hall “a project of

enormous power,” noting that it questions the urban landscape at

the same moment that it questions normative ideas of interior space making.

“Appropriate to an institution of higher learning, this exploration

clearly locates architecture within the realm of the intellectual pursuit,”

they said, concluding that it offers “a bold revision of compositional

and construction norms in American campus housing.”

The

architects envisioned this 350-bed residence as part of both the city

and campus form, calling it “a vertical slice of a city, 10 stories

tall and 330 feet long.” It provides amenities to students within

the dormitory that include a 125-seat theater and a night café.

House dining, at street level, looks and functions like a street-front

restaurant, replete with a distinctive awning and outdoor tables. Corridors

connecting the rooms are conceived of as streets inviting urban experiences.

Each of the dormitory’s single rooms has nine operable windows two-by-two-feet

in size. The 18-inch depth of the wall naturally shades out the summer

sun while allowing in the warmth and light of the low-angled winter sun.

Within the deep wall setting, color on the heads and jambs of the numerous

windows creates an identity for each of the 10 “houses” within

the overall building, and lighting at night from the nine-window rooms

is magical and exciting. The jury called the hall “a project of

enormous power,” noting that it questions the urban landscape at

the same moment that it questions normative ideas of interior space making.

“Appropriate to an institution of higher learning, this exploration

clearly locates architecture within the realm of the intellectual pursuit,”

they said, concluding that it offers “a bold revision of compositional

and construction norms in American campus housing.”

Boston Public Library, Allston Branch, by Michado and Silvetti Associates Inc., for the City of Boston Department of Neighborhood Development. Photo © Michael Moran.

This

new library is one of 27 branches in an urban system that reach out to

the city’s neighborhoods, often serving as community centers in

addition to their role of housing books. This branch is the system’s

first new freestanding facility in 20 years and represents the first time

in two decades that its local neighborhood has had a library. The $6.5

million, 20,000-square-foot building’s parti features three parallel

bands aligning with the main street: two “solid” zones and

one central void that correspond to basic programmatic functions. On the

front of the library, the architect treated the periodicals reading room

as a double-height, additive piece to give scale and material richness

to an important neighborhood building. Upon its opening in June 2002,

the branch became second in circulation among the system of 27 branches,

surpassing expectations by three times. The building houses 50,000 items

for adults, teenagers, and children, including a large literacy collection,

more than 100 newspapers and magazines, and listening and viewing stations

for compact discs, books on tape, and videos. “This project demonstrates

an expertise in craft, tectonics, and materials,” said the jury.

“The building’s façade is civic in nature yet appropriately

scaled for the neighboring houses. The inviting interior spaces are filled

with natural light and conducive to reading and research.”

This

new library is one of 27 branches in an urban system that reach out to

the city’s neighborhoods, often serving as community centers in

addition to their role of housing books. This branch is the system’s

first new freestanding facility in 20 years and represents the first time

in two decades that its local neighborhood has had a library. The $6.5

million, 20,000-square-foot building’s parti features three parallel

bands aligning with the main street: two “solid” zones and

one central void that correspond to basic programmatic functions. On the

front of the library, the architect treated the periodicals reading room

as a double-height, additive piece to give scale and material richness

to an important neighborhood building. Upon its opening in June 2002,

the branch became second in circulation among the system of 27 branches,

surpassing expectations by three times. The building houses 50,000 items

for adults, teenagers, and children, including a large literacy collection,

more than 100 newspapers and magazines, and listening and viewing stations

for compact discs, books on tape, and videos. “This project demonstrates

an expertise in craft, tectonics, and materials,” said the jury.

“The building’s façade is civic in nature yet appropriately

scaled for the neighboring houses. The inviting interior spaces are filled

with natural light and conducive to reading and research.”

Concert Hall and Exhibition Complex, Rouen, France, by Bernard Tschumi Architects, for Communaute Rouennaise. Photo © Robert Ceasar.

Called

by the jury “an inspirational, forward-thinking approach to an element

of architecture that is more routinely designed,” this new exhibition

facility provides a strong contemporary image for the cultural development

and economic expansion of the Rouen district, located 70 miles west of

Paris. The architect designed the complex to be visually interesting both

approaching and leaving Rouen on the highway. The curved steel surface

of the concert hall projects a variety of nighttime lighting effects.

The concert hall belongs to the popular, multipurpose “Zenith”

series, first developed in France by the Ministry of Culture in the 1980s

to accommodate musical events, sports spectaculars, political conventions,

and theatrical events. Additional seating allows this hall to serve audiences

of up to 8,500 people. A slight asymmetry in the seating updates the form

of the classic concert hall, lends “spontaneity” to pop music

performances, and permits the theater to be reconfigured into three smaller

volumes. The cable-tensioned roof of the hall allows an economically long

span that in turn offers long-distance visibility and great flexibility

of use. “The concert hall is powerful in its simplicity of form,”

said the jury. “The great rounded surface hovers delicately above

the ground plane, an icon in the landscape. It is extremely well-thought-out

with minute details designed to guarantee the performance of the facility.”

Called

by the jury “an inspirational, forward-thinking approach to an element

of architecture that is more routinely designed,” this new exhibition

facility provides a strong contemporary image for the cultural development

and economic expansion of the Rouen district, located 70 miles west of

Paris. The architect designed the complex to be visually interesting both

approaching and leaving Rouen on the highway. The curved steel surface

of the concert hall projects a variety of nighttime lighting effects.

The concert hall belongs to the popular, multipurpose “Zenith”

series, first developed in France by the Ministry of Culture in the 1980s

to accommodate musical events, sports spectaculars, political conventions,

and theatrical events. Additional seating allows this hall to serve audiences

of up to 8,500 people. A slight asymmetry in the seating updates the form

of the classic concert hall, lends “spontaneity” to pop music

performances, and permits the theater to be reconfigured into three smaller

volumes. The cable-tensioned roof of the hall allows an economically long

span that in turn offers long-distance visibility and great flexibility

of use. “The concert hall is powerful in its simplicity of form,”

said the jury. “The great rounded surface hovers delicately above

the ground plane, an icon in the landscape. It is extremely well-thought-out

with minute details designed to guarantee the performance of the facility.”

Bo01 “Tango” Housing, Malmo, Sweden, by Moore Ruble Yudell Architects & Planners with FFNS Arkitekter AB, for MKB Fastighets AB. Photo © Werner Huthmacher.

This

housing exposition, sponsored collaboratively by the Swedish government

and private developers, serves as a design laboratory to educate and inspire

the public with different residential scenarios. The sponsors commissioned

the architect team to design a block of 27 housing units on an 18,228-square-foot

site. Their charge was to create a progressive building in terms of sustainability,

lifestyle patterns, and integration of new technology. The architect rose

to the challenge of making each unit distinct by developing a flexible

system that articulates exterior elevations to reflect interior space.

They diminished the potential for exterior chaos of the stacked units

by imposing a “super-order grid” of ribbed, precast panels

on the perimeter of the city-block site. Internally, the project uses

a core “intelligent wall” running continuously throughout

each unit that consolidates all mechanical and technical equipment toward

the exterior walls of the block. The system accommodates tenant safety

and comfort with solutions that include hidden electrical installations,

climate control, and Internet access in all rooms. “This housing

project begins to unite European tendencies towards high-density housing

and American preferences for individual expression,” the jury commented.

“It is proof that good quality architecture can be accomplished

while environmental stewardship is maintained, and it does a great job

of building community with all of its residents.”

This

housing exposition, sponsored collaboratively by the Swedish government

and private developers, serves as a design laboratory to educate and inspire

the public with different residential scenarios. The sponsors commissioned

the architect team to design a block of 27 housing units on an 18,228-square-foot

site. Their charge was to create a progressive building in terms of sustainability,

lifestyle patterns, and integration of new technology. The architect rose

to the challenge of making each unit distinct by developing a flexible

system that articulates exterior elevations to reflect interior space.

They diminished the potential for exterior chaos of the stacked units

by imposing a “super-order grid” of ribbed, precast panels

on the perimeter of the city-block site. Internally, the project uses

a core “intelligent wall” running continuously throughout

each unit that consolidates all mechanical and technical equipment toward

the exterior walls of the block. The system accommodates tenant safety

and comfort with solutions that include hidden electrical installations,

climate control, and Internet access in all rooms. “This housing

project begins to unite European tendencies towards high-density housing

and American preferences for individual expression,” the jury commented.

“It is proof that good quality architecture can be accomplished

while environmental stewardship is maintained, and it does a great job

of building community with all of its residents.”

American Folk Art Museum, New York City, by Tod Williams Billy Tsien Architects, with Associate Architect Helfand Myerberg Guggenheimer Architects, for The American Folk Art Museum. Photo © Michael Moran.

Located

on West 53rd Street in New York City, this new eight-level building devotes

its four upper floors to gallery space for permanent and temporary exhibitions.

A skylight caps a grand interior stair with openings at each floor that

allow natural light to filter into the galleries and through to lower

levels. The design allows for art to be integrated into public spaces

by offering a series of niches throughout the building that offer informal

interaction with a changing series of folk-art objects. The museum visitor

encounters an architectural journey. Surprising encounters with both new

and familiar objects are fostered by multiple and sometimes redundant

paths of circulation. Display of the museum’s collections and exhibitions,

through both straightforward and nontraditional spaces, creates a comfortable

environment for adults and children and frequent and first-time visitors

alike. The jury termed this project “a unique approach to architectural

design with products of enough quality to begin new trends within the

industry; great mix, great styling.” They also found the investigation

into materials exciting: “It also showed a great understanding of

the scale of folk art.”

Located

on West 53rd Street in New York City, this new eight-level building devotes

its four upper floors to gallery space for permanent and temporary exhibitions.

A skylight caps a grand interior stair with openings at each floor that

allow natural light to filter into the galleries and through to lower

levels. The design allows for art to be integrated into public spaces

by offering a series of niches throughout the building that offer informal

interaction with a changing series of folk-art objects. The museum visitor

encounters an architectural journey. Surprising encounters with both new

and familiar objects are fostered by multiple and sometimes redundant

paths of circulation. Display of the museum’s collections and exhibitions,

through both straightforward and nontraditional spaces, creates a comfortable

environment for adults and children and frequent and first-time visitors

alike. The jury termed this project “a unique approach to architectural

design with products of enough quality to begin new trends within the

industry; great mix, great styling.” They also found the investigation

into materials exciting: “It also showed a great understanding of

the scale of folk art.”

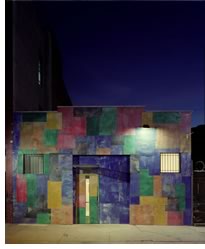

Heritage Health and Housing, New York City, by Caples Jefferson Architects, for Heritage Health and Housing. Photo © Albert Vecerka.

“This

is an example of dedicated architects taking on what could have been seen

as a marginal project from a budgetary point of view,” said the

jury of this colorful project in Harlem. “There is real intelligence

in how the architects used simple materials, details, and spatial organization

to transform the interior of the original building.” Inspiration

came directly from the client, the people of Heritage Health and Housing

who provide services and housing for recent offenders with a history of

mental illness and, often, substance abuse. They asked for an environment

that “looks like us” and offers some moments of order and

hope. Much of the project’s construction had to be field-directed,

as the contractor could not read the plans and drawings. One of its most

striking aspects is four light shafts piercing the dark interior of the

narrow through-block building, offering light in “spots” so

that changes in light quality can be quickly perceived. “To accomplish

so much with so little is exceptional, and to pair it with the nobility

of its social impact is difficult to overlook,” the jury concluded.

“This

is an example of dedicated architects taking on what could have been seen

as a marginal project from a budgetary point of view,” said the

jury of this colorful project in Harlem. “There is real intelligence

in how the architects used simple materials, details, and spatial organization

to transform the interior of the original building.” Inspiration

came directly from the client, the people of Heritage Health and Housing

who provide services and housing for recent offenders with a history of

mental illness and, often, substance abuse. They asked for an environment

that “looks like us” and offers some moments of order and

hope. Much of the project’s construction had to be field-directed,

as the contractor could not read the plans and drawings. One of its most

striking aspects is four light shafts piercing the dark interior of the

narrow through-block building, offering light in “spots” so

that changes in light quality can be quickly perceived. “To accomplish

so much with so little is exceptional, and to pair it with the nobility

of its social impact is difficult to overlook,” the jury concluded.

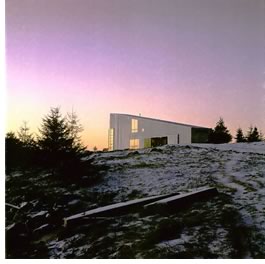

Howard House, West Pennant, Nova Scotia, by Brian MacKay-Lyons Architecture Urban Design, for Vivian and David Howard. Photo © James Steeves, Atlantic Stock Images.

“The

tectonic of the construction, the beauty of vernacular, and the purist

sense of shelter are all part of this enchanting home,” said the

jury of this modest house with its 12-foot-wide, 110-foot-long wall that

plays a didactic role within both the natural and cultural landscapes.

The project sits on a four-acre field surrounded by the sea on three sides:

east to a domesticated fishing cove, west to the nearby wild, open ocean,

and south to the immediate shore of a bay. Its “rough and ready”

wrapper is standard, industrial, corrugated galvanized aluminum. The top-of-concrete

line of the foundation is raised, symbolizing the relatively high cost

of getting out of the ground in cold climates and forming a horizontal

anchor against the opposing slopes of land and roof. The monolithic, monopitch

roof climbs to the south and covers one continuous, unobstructed living

space that progresses from garage, entry court, and kitchen to living

room and cantilevered deck. Three bedrooms occupy the lower level, and

the master bedroom/study occupies a second-floor loft. The house exploits

a passive environmental approach to heating and ventilation. “The

opportunity it offers, in contrast with the everyday solution, needs to

be recognized so that more people can understand the possibilities of

architecture regardless of the budget,” the jury opined.

“The

tectonic of the construction, the beauty of vernacular, and the purist

sense of shelter are all part of this enchanting home,” said the

jury of this modest house with its 12-foot-wide, 110-foot-long wall that

plays a didactic role within both the natural and cultural landscapes.

The project sits on a four-acre field surrounded by the sea on three sides:

east to a domesticated fishing cove, west to the nearby wild, open ocean,

and south to the immediate shore of a bay. Its “rough and ready”

wrapper is standard, industrial, corrugated galvanized aluminum. The top-of-concrete

line of the foundation is raised, symbolizing the relatively high cost

of getting out of the ground in cold climates and forming a horizontal

anchor against the opposing slopes of land and roof. The monolithic, monopitch

roof climbs to the south and covers one continuous, unobstructed living

space that progresses from garage, entry court, and kitchen to living

room and cantilevered deck. Three bedrooms occupy the lower level, and

the master bedroom/study occupies a second-floor loft. The house exploits

a passive environmental approach to heating and ventilation. “The

opportunity it offers, in contrast with the everyday solution, needs to

be recognized so that more people can understand the possibilities of

architecture regardless of the budget,” the jury opined.

Hypo Alpe-Adria-Center, Klagenfurt, Austria, by Morphosis, for Hypo Alpe-Adria-Carinthia. Photo © Christian Richters.

“This

project questions the materiality and configuration of the office/commercial

structure, as we have come to understand them, and resolves itself in

refreshingly smart ways,” said the jury of the new Hypo Center by

Morphosis. It’s a great accomplishment . . . using architecture

to put this city on the map and create community within a city.”

The architects report that they attempted to engage both the urban and

rural forces at play on the site: transforming found elements of the city,

interpreting existing infrastructure and building types, and “striating

the roof surface with lines that echo the directionality of furrows in

surrounding fields.” The design means to give voice to conflicting

forces and thus “harness the dynamic of global connectivity.”

The project’s forms triangulate around an open pedestrian forum,

and large entrance canopy gestures welcome. A vast, curved roof “landscape”

shelters the bank’s headquarters, an event center, commercial space,

and offices. Within the central complex, a skylighted courtyard serves

both as an organizing element and as a source of light that penetrates

down to the ground-floor branch bank.

“This

project questions the materiality and configuration of the office/commercial

structure, as we have come to understand them, and resolves itself in

refreshingly smart ways,” said the jury of the new Hypo Center by

Morphosis. It’s a great accomplishment . . . using architecture

to put this city on the map and create community within a city.”

The architects report that they attempted to engage both the urban and

rural forces at play on the site: transforming found elements of the city,

interpreting existing infrastructure and building types, and “striating

the roof surface with lines that echo the directionality of furrows in

surrounding fields.” The design means to give voice to conflicting

forces and thus “harness the dynamic of global connectivity.”

The project’s forms triangulate around an open pedestrian forum,

and large entrance canopy gestures welcome. A vast, curved roof “landscape”

shelters the bank’s headquarters, an event center, commercial space,

and offices. Within the central complex, a skylighted courtyard serves

both as an organizing element and as a source of light that penetrates

down to the ground-floor branch bank.

Lever House Curtain Wall Replacement, New York City, by Skidmore Owings & Merrill LLP, for RFR Holdings. Photo © SOM, by Ezra Stoller/ESTO Photographics.

The

Lever House’s 1952 opening marked a watershed in U.S. architecture.

The 24-story corporate headquarters, clad in blue-green glass and stainless-steel

mullions, offered one of the first U.S. glass-walled International Style

buildings. By day, its façade shimmered in the sun; by night, it

glowed like a lantern. Within a decade of its construction, the initial

enthusiasm for the beauty of the project gave way to a universal recognition

of its pivotal importance to American architecture. Finally, in 1992,

the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated it as an

official landmark. By that time, however, its walls, dulled by harsh weather

conditions, had lost most of their brilliance. Water has seeped behind

the stainless steel mullions, causing the carbon steel to rust and expand,

bowing the mullions, and breaking all but one percent of the original

glass. The jury noted this project’s sophisticated techniques to

maintain the original building’s appearance. Beginning in 1998,

the sub-frame was replaced with concealed aluminum glazing channels, making

the new curtain wall identical to the original in appearance. New glass

panes have replaced all of the old, and all mullions and caps were replaced

with new ones made of stainless steel. The entire restoration was completed

in December 2001. “The precedent this building represents in preserving

the roots of Modernism is undeniable. We can only hope that it forecasts

the future of preservation and offers a greater sense of understanding

to those who have illustrated a very finite sense of how preservation

has been practiced in recent years,” the jury concluded.

The

Lever House’s 1952 opening marked a watershed in U.S. architecture.

The 24-story corporate headquarters, clad in blue-green glass and stainless-steel

mullions, offered one of the first U.S. glass-walled International Style

buildings. By day, its façade shimmered in the sun; by night, it

glowed like a lantern. Within a decade of its construction, the initial

enthusiasm for the beauty of the project gave way to a universal recognition

of its pivotal importance to American architecture. Finally, in 1992,

the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated it as an

official landmark. By that time, however, its walls, dulled by harsh weather

conditions, had lost most of their brilliance. Water has seeped behind

the stainless steel mullions, causing the carbon steel to rust and expand,

bowing the mullions, and breaking all but one percent of the original

glass. The jury noted this project’s sophisticated techniques to

maintain the original building’s appearance. Beginning in 1998,

the sub-frame was replaced with concealed aluminum glazing channels, making

the new curtain wall identical to the original in appearance. New glass

panes have replaced all of the old, and all mullions and caps were replaced

with new ones made of stainless steel. The entire restoration was completed

in December 2001. “The precedent this building represents in preserving

the roots of Modernism is undeniable. We can only hope that it forecasts

the future of preservation and offers a greater sense of understanding

to those who have illustrated a very finite sense of how preservation

has been practiced in recent years,” the jury concluded.

3rd & Benton, 7th & Grandview Primary Centers, Los Angeles, by Rios Associates Inc., for Los Angeles Unified School District. Photo © Jonathan Dewdney.

To

reduce class size in existing schools, the Los Angeles Unified School

District set about developing primary centers—self-sufficient schools

for children in kindergarten through second grade—on small one-

or two-acre sites. The project team developed a prototypical set of buildings

and site-planning strategies for this new program type and adapted them

to two sites located within a mile of each other. The architect based

the classroom prototype on a prescribed “relocatable” 24-foot-by-48-foot

classroom unit. Classroom modules are paired to allow for window exposure

on three sides of each room, and an inverted roof allows clerestory windows

to light each classroom and administrative areas naturally. Like the classroom

module, the prototypical site plan reflects the district’s concern

for security and flexible outdoor spaces. Buildings flank the perimeter

of the site with block walls in between, forming an undulating yet solid,

secure edge. Landscaped courts serve as foyers or “outdoor classrooms”

to the buildings they front. Like fingers on a hand, these courts connect

to a large play area furnished with a colorful “carpet” of

sports courts and games painted with traffic and tennis court paint. “The

project demonstrates how graphics and architecture can be integrated to

create identity and meaning,” the jury said. “The images provide

each school with its own identity and serve to link the buildings with

their sign-covered contexts. Ultimately, the project suggests that everyday

architecture fashioned intelligently from inexpensive materials can be

incredibly successful.”

To

reduce class size in existing schools, the Los Angeles Unified School

District set about developing primary centers—self-sufficient schools

for children in kindergarten through second grade—on small one-

or two-acre sites. The project team developed a prototypical set of buildings

and site-planning strategies for this new program type and adapted them

to two sites located within a mile of each other. The architect based

the classroom prototype on a prescribed “relocatable” 24-foot-by-48-foot

classroom unit. Classroom modules are paired to allow for window exposure

on three sides of each room, and an inverted roof allows clerestory windows

to light each classroom and administrative areas naturally. Like the classroom

module, the prototypical site plan reflects the district’s concern

for security and flexible outdoor spaces. Buildings flank the perimeter

of the site with block walls in between, forming an undulating yet solid,

secure edge. Landscaped courts serve as foyers or “outdoor classrooms”

to the buildings they front. Like fingers on a hand, these courts connect

to a large play area furnished with a colorful “carpet” of

sports courts and games painted with traffic and tennis court paint. “The

project demonstrates how graphics and architecture can be integrated to

create identity and meaning,” the jury said. “The images provide

each school with its own identity and serve to link the buildings with

their sign-covered contexts. Ultimately, the project suggests that everyday

architecture fashioned intelligently from inexpensive materials can be

incredibly successful.”

Diamond Ranch High School, Pomona, Calif., by Morphosis with Associate Architect Thomas Blurock Architects, for Pomona Unified School District. Photo © Kim Zwarts.

“The

complete nature of the theory and built form offers a great deal of hope

for the future,” the jury said about the careful study invested

by the architects in creating this high school. The first major study

directed how the project was to be sited. The second strategy centered

on a social agenda defining school culture and the pedagogical impact

of architecture. Based on analysis of the current state of the public

secondary education, the project became an “urban” problem,

encouraging traffic along a principal pedestrian “sidewalk”

and creating open pockets for chance encounters and unprogrammed learning

environments. The architects explain that they “explored the hybrid

territory between building and site, attempting to transcend the traditional

figure-ground opposition of passive site and active building.” They

made the site a “manipulated landscape” by activating all

elements and blurring the boundaries of built and natural. “The

exploration offered by this building and the challenges that it presents

to the archetype of the school is an exciting proposition,” the

jury commented. “In so many ways, this building disproves all those

who say that progressive architecture cannot be realized under the discipline

of a public-school budget.”

“The

complete nature of the theory and built form offers a great deal of hope

for the future,” the jury said about the careful study invested

by the architects in creating this high school. The first major study

directed how the project was to be sited. The second strategy centered

on a social agenda defining school culture and the pedagogical impact

of architecture. Based on analysis of the current state of the public

secondary education, the project became an “urban” problem,

encouraging traffic along a principal pedestrian “sidewalk”

and creating open pockets for chance encounters and unprogrammed learning

environments. The architects explain that they “explored the hybrid

territory between building and site, attempting to transcend the traditional

figure-ground opposition of passive site and active building.” They

made the site a “manipulated landscape” by activating all

elements and blurring the boundaries of built and natural. “The

exploration offered by this building and the challenges that it presents

to the archetype of the school is an exciting proposition,” the

jury commented. “In so many ways, this building disproves all those

who say that progressive architecture cannot be realized under the discipline

of a public-school budget.”

Will Rogers World Airport Snow Barn, Oklahoma City, by Elliott + Associates Architects, for Department of Airports. Photo © Bob Shimer/Hedrich Blessing.

This

18,000-square-foot structure’s reason for being is to serve as an

off-duty home for airport snow-removal equipment, with ancillary offices,

support functions, and mechanical areas. The architecture team provided

an efficient, functional, and economical space within which personnel

will be able to maneuver, park, and maintain the expensive equipment for

years to come. The architect transformed standardized building systems

into memorable forms that relate to the concept of flight. Soaring wedge

shapes, reflective fuselage materials, and caution-yellow accents celebrate

the building’s industrial function. Monumental bollards protect

walls, corrugated metal panels reflect sun and heat, translucent white

fiberglass wall panels provide light diffusion, and monumental overhead

doors do double duty as art panels. “Without reverting to superfluous

gestures, the architects found every opportunity to orchestrate a beautiful

and functional design. No detail was overlooked or deemed too insignificant

to be considered,” according to the jury. “It is a work of

intelligence, creativity, and craft on a building type that rarely is

considered architecture. If every utility building were designed with

this care, the world would be a much more beautiful and interesting place.”

This

18,000-square-foot structure’s reason for being is to serve as an

off-duty home for airport snow-removal equipment, with ancillary offices,

support functions, and mechanical areas. The architecture team provided

an efficient, functional, and economical space within which personnel

will be able to maneuver, park, and maintain the expensive equipment for

years to come. The architect transformed standardized building systems

into memorable forms that relate to the concept of flight. Soaring wedge

shapes, reflective fuselage materials, and caution-yellow accents celebrate

the building’s industrial function. Monumental bollards protect

walls, corrugated metal panels reflect sun and heat, translucent white

fiberglass wall panels provide light diffusion, and monumental overhead

doors do double duty as art panels. “Without reverting to superfluous

gestures, the architects found every opportunity to orchestrate a beautiful

and functional design. No detail was overlooked or deemed too insignificant

to be considered,” according to the jury. “It is a work of

intelligence, creativity, and craft on a building type that rarely is

considered architecture. If every utility building were designed with

this care, the world would be a much more beautiful and interesting place.”

Copyright 2003 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved.

![]()

| Institute Honor Awards for Architecture Jury: Chair Jack Hartray, FAIA Paul Byard, FAIA Merrill Elam, AIA Mary Griffin, AIA Vincent James, AIA Michael D. Perry, Hon. AIA Barton Phelps, FAIA Ryan Sullivan Thomas J. Trenolone, Assoc. AIA See also: |

|