An interview with Kim Sorvig, ASLA

Drought

or flood, landscaping can make a difference. To work with water, a well-conceived

landscape plan will include at least three strategic elements: the right

plantings for your region; soil conditioning, ideally with compost; and

a maintenance plan the owner understands and is able to undertake.

Drought

or flood, landscaping can make a difference. To work with water, a well-conceived

landscape plan will include at least three strategic elements: the right

plantings for your region; soil conditioning, ideally with compost; and

a maintenance plan the owner understands and is able to undertake.

Plant for your regional

conditions

Unfortunately, the last 75 years of architectural and landscape architectural

theory have inclined many of us to ignore regional nuance. San Diego,

Phoenix, and Seattle may all have drought problems (despite the image

everyone has of Seattle practically drowning in rain all year), but each

has its own climatic considerations. You cannot have a standard answer

to plant selection that's going to fit every region.

To design within the regional water budget, use native plants, if you can find ones that serve your purposes. This is almost always possible if you're thinking creatively. Think in terms of texture and form as well as showy flowers. (Many native plants have those too.) The result, because natives tend to have lower water requirements once they are established, is lower water consumtion requirements and often lower maintenance overall.

Of course you really have to look into what is regionally native. My advice there is not to get too nitpicky. There will always be controversy over how to define "native species." But people should not let those arguments about what is and isn't native dictate plant selection. To me, the deciding factor is what thrives with little or no additional water in the specified region. To get the answer to that question generally requires teaming with someone local.

There are a large number of landscape architects who know their native plants very well. If you cannot find such an expert for the area in which you are working, look for anybody who has done native plant work there in the past, including nurseries that specialize in native flora.

One word for the

future: compost

Water conservation is not something that happens in isolation. We're finding

more and more that everything we do has connections to just about everything

else as soon as you get outdoors. There's even fairly distressing evidence

that links the big cycle of drought in Africa with pollution from other

continents—from tropical-forest slash-and-burn to industrial discharges.

Banal as one major solution may sound, focusing on the soil will ensure

both better water quality and overall water conservation. This is something

frequently overlooked as an irrelevant cost.

One of the very best things you can do for soil conditioning—whether it's to restore soil that has been slightly damaged during construction or build new soil because the topsoil has been lost altogether—is compost. Although not particularly glamorous, the benefits of compost work equally on sandy soil and clay soil, which are the two main problems with water availability in the soil. By adding compost and organic matter, you increase the availability of water, not just the presence of it. You also improve the cohesiveness of the soil, which decreases soil erosion, which decreases sedimentation. Organic-rich soil acts as a sponge, holding water during heavy rain and releasing it gradually, keeping plants watered and riverine levels stable. At the same time, the microorganisms that live in the soil are greatly increasing the biofiltration that goes on. So the combination of reduced erosion and sedimentation and better biofiltration means that you have a very significant regional effect on water quality in aquifers and surface waters. And that, of course, turns back onto the question of water supply and water conservation, because if your water isn't as polluted, there is less to be done to make it potable.

Composting

ought to be undertaken at every level of scale. Municipal composting is

critically important, not only for the use of the compost but for keeping

things out of landfills, for which we can't waste the space or money.

Commercial facilities, also, have both the responsibility and ability

to incorporate composting into their landscape maintenance plan. Ideally,

have the landowner or land user do the composting, since this keeps the

whole organic material cycle on-site. Of course, all this relies on willingness

and ability. This is not to say that composting takes a great deal of

skill, but it certainly requires some basic attention to the process.

Interestingly (but not surprisingly) that attention is often more readily

gotten from commercial clients than residential ones.

Composting

ought to be undertaken at every level of scale. Municipal composting is

critically important, not only for the use of the compost but for keeping

things out of landfills, for which we can't waste the space or money.

Commercial facilities, also, have both the responsibility and ability

to incorporate composting into their landscape maintenance plan. Ideally,

have the landowner or land user do the composting, since this keeps the

whole organic material cycle on-site. Of course, all this relies on willingness

and ability. This is not to say that composting takes a great deal of

skill, but it certainly requires some basic attention to the process.

Interestingly (but not surprisingly) that attention is often more readily

gotten from commercial clients than residential ones.

The all-important

maintenance plan

All landscape designs should include maintenance plans that the owner/operator

understands from the outset. Too many times designers get a design down

on paper, hand it off to someone else, and walk away. Often that handoff

happens twice: the handoff to the contractor, who builds it and then hands

off the result to an owner, who very well may in turn hand the maintenance

responsibilities off to another party altogether. There's just not enough

coordination of facility operation, which is so crucial to life-cycle

cost and durability.

If conservation is a concern, and it absolutely should be, the landscape designer should work with a maintenance expert from day one. The handoff to the owner needs to include real as-built drawings (not as-supposedly-built drawings), a list of seasonal tasks, and estimates of how long each task will take so that the owner/operator can plan ahead realistically for all maintenance tasks. A solid maintenance plan can conserve 50 percent of a facility's annual water use while producing a better landscape.

Copyright 2002 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved.

![]()

|

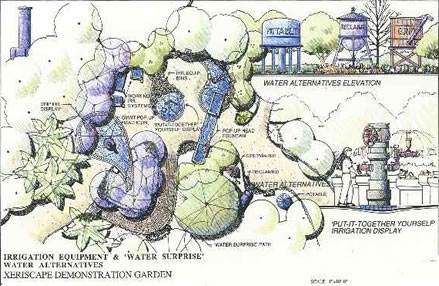

Kim Sorvig is a lecturer and author on landscape issues and maintains a highly selective design practice. He is a presenter at the 2002 AIA Western Mountain Region conference September 5–8 in Albuquerque. His latest book is Sustainable Landscape Construction: A Guide to Green Building Outdoors, Island Press, which gives much more of a sense than this article can of the overall strategies of sustainable landscape design beyond (but certainly including) water conservation. Many of the points Sorvig brings up here illustrate the Seven Principles of Xeriscape. To see a synopsis of Kim Sorvig's August 2002 Landscape Architecture article "Garden for a Dry Planet," which explores the Water Conservation Garden in San Diego, illustrated here, visit the ASLA Web site. Illustrations and photograph courtesy of the Deneen Powell Atelier designers of the Water Conservation Garden. |

|