Tributes by

George E. Hartman, FAIA; Bill Lacy, FAIA; and

Raymond P. Rhinehart, Hon. AIA

Within

the architecture community, J. Carter Brown, Hon. AIA, who passed away

June 17 at the age of 67, was best known for bringing the arts to the

American public. As director of the National Gallery of Art from 1969

to 1992, jury chair for the Pritzker Prize since its inception, and chair

of the Commission of Fine Arts from 1971 until his resignation for health

reasons on May 30, "J. Carter Brown was a faithful advocate for shaping

our environments so our experiences will be elevated and enriched,"

as recently characterized by AIA Executive Vice President/CEO Norman L.

Koonce, FAIA. And clearly there were other facets to Brown's dynamism,

which attracted heartfelt admiration from many, many people. George E.

Hartman, FAIA; Bill Lacy, FAIA; and Raymond P. Rhinehart, Hon. AIA, share

some of those facets in the tributes below.

Within

the architecture community, J. Carter Brown, Hon. AIA, who passed away

June 17 at the age of 67, was best known for bringing the arts to the

American public. As director of the National Gallery of Art from 1969

to 1992, jury chair for the Pritzker Prize since its inception, and chair

of the Commission of Fine Arts from 1971 until his resignation for health

reasons on May 30, "J. Carter Brown was a faithful advocate for shaping

our environments so our experiences will be elevated and enriched,"

as recently characterized by AIA Executive Vice President/CEO Norman L.

Koonce, FAIA. And clearly there were other facets to Brown's dynamism,

which attracted heartfelt admiration from many, many people. George E.

Hartman, FAIA; Bill Lacy, FAIA; and Raymond P. Rhinehart, Hon. AIA, share

some of those facets in the tributes below.

A Slight

Luff to Ease the Load

by George E. Hartman, FAIA

While best known as director of the National Gallery of Art or the longest-serving chair of the Commission of Fine Arts, J. Carter Brown was also a highly accomplished sailor. He was an esteemed member of the Cruising Club of America and participated in the Newport-to-Bermuda race, a rigorous, 1,000-mile passage across the Atlantic for which only the most seasoned sailor qualifies.

I

learned something of Carter the day he sailed the Chesapeake Bay with

me on my 40-year-old wooden Concordia yawl, Woodwind. He was an excellent

and very considerate helmsman. Tacking a boat—shifting 90 degrees

from one direction to another—requires easing and trimming sails,

to shift the wind in the Dacron sails that power the boat. As he tacked,

Carter would always give you a slight luff in the sails to ease the load

as you winched in the headsails. Perhaps he used the same instincts in

running a meeting of the Commission—he gave proponents and opponents

alike some slack in their course, even in the roughest waters, yet he

always retained control of the helm and usually had a pretty good idea

of the ultimate outcome.

I

learned something of Carter the day he sailed the Chesapeake Bay with

me on my 40-year-old wooden Concordia yawl, Woodwind. He was an excellent

and very considerate helmsman. Tacking a boat—shifting 90 degrees

from one direction to another—requires easing and trimming sails,

to shift the wind in the Dacron sails that power the boat. As he tacked,

Carter would always give you a slight luff in the sails to ease the load

as you winched in the headsails. Perhaps he used the same instincts in

running a meeting of the Commission—he gave proponents and opponents

alike some slack in their course, even in the roughest waters, yet he

always retained control of the helm and usually had a pretty good idea

of the ultimate outcome.

Having served on the commission under Carter in the mid-1980s and having consulted with him over four decades on mutual design projects, I believe only when sailing was Carter completely relaxed and focused solely on the task at hand. Like many sailors, watching the wind on the water was Carter's one preoccupation when under sail, rather than his usual diverse range of multiple concerns.

Carter was extremely knowledgeable about the sport of sailing. He once sketched a sectional drawing of a Dorade vent during a Commission of Fine Arts meeting, explaining the Sparkman & Stevens invention and the source of the name. He suggested that a similar design might allow Metro stations to ventilate the subway while keeping out water, just as they do on boats. Carter came by all this honestly as the son of John Nicholas Brown, who died in the arms of his captain on his boat, Malaguana. This is the boat Carter learned to sail on, a classic 50-foot yawl made by Hinckley of Southwest Harbor, Maine. Malaguana is now in the Chesapeake Bay, where its subsequent owner has lovingly maintained it to the Brown family's taste and standards.

George Hartman is principal and founder of Washington, D.C.'s illustrious Hartman·Cox Architects, former member of the Commission of Fine Arts, and an avid sailor.

My

Travels with J. Carter Brown, Hon. AIA

by Bill Lacy, FAIA

J. Carter Brown was an eager advocate and a fan, a true architect manqué, if there ever was one. That is what disappointed me about much of the coverage that followed his death: The obituaries and lengthy tributes rightly called attention to the great figure he cut in the art world, and they were absolutely on the mark about his brilliance as a raconteur and connoisseur.

But his passion for architecture and architects—this did not get nearly the attention it deserved.

My association with Carter began in 1971 when I came to Washington to run the National Endowment for the Arts' Architecture and Design Program. Carter Brown was already a major force in art, architecture, and design, so there were any number of reasons for our paths to cross.

At the time, the NEA was deeply involved in saving Washington's Old Post Office as well as critiquing the Pennsylvania Avenue plan and directing a Federal Design Implementation program. As we grappled with the complex aesthetic, economic, and political issues stirred up by these projects, I quickly came to appreciate just how absolutely knowledgeable Carter was about architecture.

In

one sense, his knowledge and passion were not all that surprising. After

all, Carter Brown was born and bred surrounded by the very best. After

his funeral service in Providence, we went back to the house he grew up

in, his family's marvelous historic home on Benefit Street. Just looking

around, you could see that it had a significant effect on him, as did

Windshield, the summer home his father commissioned from Richard Neutra,

FAIA.

In

one sense, his knowledge and passion were not all that surprising. After

all, Carter Brown was born and bred surrounded by the very best. After

his funeral service in Providence, we went back to the house he grew up

in, his family's marvelous historic home on Benefit Street. Just looking

around, you could see that it had a significant effect on him, as did

Windshield, the summer home his father commissioned from Richard Neutra,

FAIA.

Carter used to regale us with stories about his father's intensive interaction with Neutra. Being able to listen in on the entire design process of that extraordinary commission obviously opened his eye and sensibility to the excitement of modern architecture, which is why I was so pleased that before he died he was able to see Dietrich Neumann's fine book on Windshield and participate in creating a wonderful exhibition organized by the Harvard University Art Museum. For the opening last November, Carter delivered one of the finest video and audio presentations I have witnessed in a long time. By the time he came to that part of the story when the house is destroyed by fire, there wasn't a dry eye in the crowd.

In those first years after we met, our professional association rapidly grew into a close friendship, especially when I took on the responsibility of running the Pritzker Prize, whose jury Carter had chaired ever since its inception in 1979. We began to spend a lot of time traveling together, not simply for the annual ceremonies but, most importantly, to see the architecture.

On those trips Carter never stopped moving. It was just fantastic to watch him operate. We would land in, say, Spain, get packed into a van, and immediately set out to visit several cities—all in one day. By the time evening came, we would be limp from the walking and talking and being taken around. But about a mile from the hotel, Carter would get out of the van and say, "You go on. I'm going to walk the rest of the way. I want to see what this town is like"

Even then he wouldn't stop. After dinner, he would go up to his room where he would happily sit at his laptop answering dozens of e-mails that had come that day. I cannot imagine how he found the time to sleep! I have never seen such an indefatigable individual or anyone who was so keen to learn and see as much as he possibly could in one lifetime.

He was so devoted to the Prtizker Prize that he would not allow health matters to stand in the way of his commitment to its mission to honor the significant contributions of architects to humanity and the built environment. Last year in February, shortly after finishing a debilitating round of therapy, he let it be known he did not want to miss the jury's regularly scheduled meeting. Could we come to Boston, he asked, where he was convalescing? He advised us that if we did, we'd have to wear masks, because he could not take any chances with getting an infection. Of course we went, but not before sending all the materials he requested for his review so that he would be prepared to take an active role in the discussion.

I remember once trying to get dressed in a small private jet on the way to Chicago. We were cutting it close, because, as usual, Carter was doing more than any individual could do in a day. He and I were hunched over in the aisle, struggling with our tuxes, as the plane bounced in the air, and I looked at him and said, "This is the craziest thing I've ever seen!" On the ground an hour later, I was introducing him at the Chicago Art Institute where he went on to deliver a brilliant talk, as usual.

Carter Brown could have easily had the career and life his father led, collecting art and giving money away. But he loved architecture too much for that. Given another life to live, I am sure he would have lived it as an architect.

Bill Lacy is the president of Purchase College/State University of New York and the executive director of the Pritzker Architecture Prize.

Giving

the Angel Its Wings

by Raymond P. Rhinehart, Hon. AIA

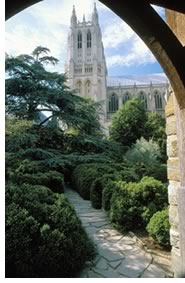

The

back of J. Carter Brown's head was a tangle of loose sandy curls that

grew lighter over the years. As a fellow subscriber to a National Cathedral

concert series, I watched the graying of one of the Capital's most preeminent

citizens from a privileged position two rows back and slightly to the

right. Often he brought his son, who cut a somewhat slighter profile,

but the fine tangle of hair that spilled over his shirt collar made him

a dead ringer for his dad.

The

back of J. Carter Brown's head was a tangle of loose sandy curls that

grew lighter over the years. As a fellow subscriber to a National Cathedral

concert series, I watched the graying of one of the Capital's most preeminent

citizens from a privileged position two rows back and slightly to the

right. Often he brought his son, who cut a somewhat slighter profile,

but the fine tangle of hair that spilled over his shirt collar made him

a dead ringer for his dad.

Carter was passionate about music. His mother had seen to that. And so when he wasn't planning blockbuster exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art or skillfully steering the Fine Arts Commission through the shoals of Washington politics, he grabbed whatever spare time he could to attend musical productions all around town.

However, as he was heard to say on several occasions, whether from a full orchestra or a single instrument, the pleasure was magically enhanced by the space in which the performance took place. Music wasn't for him solely a matter of technique or acoustics, although both were of course important. Music, or at least the experience of it, was also what the eye could see. At its best, music was for Carter the sum of all the senses engaged. If that included incense, so much the better.

More than an intelligent listener, Carter was also a friend of music, which is how I came to know him.

Seven years ago, Washington's Cathedral Choral Society (CCS) decided to create a new honor, the Laura E. Phillips Angel of the Arts Award, named after one of the society's most generous benefactors. As someone who had once sung with the CCS, Carter was asked to use his good offices to persuade his patron, Paul Mellon, to be the award's first recipient. Mellon's many contributions to all the arts certainly qualified him. Moreover, his acceptance would position the new award as an honor of some importance in Washington's arts community.

At first, Mellon was reluctant to accept. Although he, too, was a generous supporter of the CCS, he was well on in years and not in the best of health. Besides, for all his visibility as a great patron, he was a private man who did not seek the spotlight. But Carter wasn't someone to be denied once he was on a mission, and his consummate diplomatic skills prevailed. This Angel had wings.

Late last summer the now-established awards committee met over lunch to select an Angel who would be honored at the annual CCS gala this past spring. As a singer and CCS trustee, I was on that committee along with Carter who, uncharacteristically, was late, so we began the meeting without him. Yet his very absence was a kind of presence, and in short order, one of us came up with a novel idea: What about Carter? Wasn't he the obvious frontrunner? Of course, and with that settled, we became caught up in a much more difficult matter: What were the names of the Seven Dwarfs? We came up with only six.

At that point, Carter arrived, his craggy patrician face looking more angular and pale than usual. We all knew he had been battling a life-threatening illness, but his quick wit and energy belied just how serious his condition was. "I apologize for being late," he said. "I see you've started the meeting. What are you talking about?"

"We're trying to remember the names of all the Seven Dwarfs, but we're stuck at six." "Who have you got?" he asked. As soon as we quieted down, he said without missing a beat, "It's Doc."

We then moved on to the business at hand and conveyed our unanimous decision that the 2002 recipient of the Angel of the Arts Award should be J. Carter Brown. Clearly surprised, he sat back in his chair. "I suppose I'm outvoted," was his reply. Then he smiled and said, "Well, I guess I'll have to live long enough to receive it."

The CCS gala last April was to be Carter's last public appearance in Washington. The acceptance speech he gave that night to a room crowded with his friends and admirers spoke of the profound joy music gave him, especially when performed in a space as grand as that of the National Cathedral. The easy erudition and gentle humor together with the passionate sparkle of his eyes were the measure of a man at the top of his form, a man who had given so much of his life to the arts and to whom the arts had given so much in return.

In retrospect, it was only fitting that he gave the final words to England's great poet, John Milton, as he recited from memory the following lines from the elegiac poem Il Penseroso:

And storied windows richly dight,

Casting a dim religious light.

There let the pealing organ blow,

To the full-voiced choir below,

In service high, and anthems clear

As may, with sweetness, through mine ear

Dissolve me into ecstasies,

And bring all Heaven before mine eyes.

Ray Rhinehart is the AIA's senior director

of special programs, and a longtime member of Washington's Cathedral Choral

Society. He sings—and writes—like an angel.

Copyright 2002 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved.

![]()

|

|

|