Associate Editor

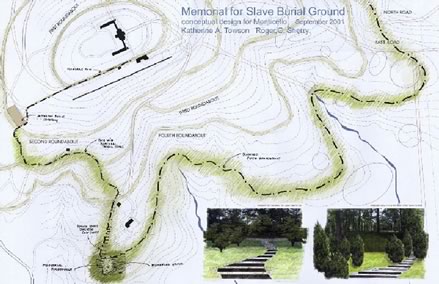

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc., selected two design concepts rich in symbolism and cultural reference to mark the site of an African American burial ground at Monticello.

Although

the jurors intended to select only one proposal, the complementing designs,

submitted by Lance Hosey, AIA, and the team of landscape architects, Katherine

A. Towson and Roger Charles Sherry, were ultimately paired together.

Although

the jurors intended to select only one proposal, the complementing designs,

submitted by Lance Hosey, AIA, and the team of landscape architects, Katherine

A. Towson and Roger Charles Sherry, were ultimately paired together.

"Together, these designs will provide an avenue of reflection and a space for contemplation of the humanity that endured in conditions of slavery," said Sara Bon-Harper, Monticello's archaeological research manager and chair of the committee that selected the designs.

"They will produce a fitting tribute to Monticello's enslaved community," she said.

"Fitting tribute"

In creating his design, Hosey, an associate at William McDonough + Partners,

Charlottesville, Va., said he drew from research on Monticello and Thomas

Jefferson.

"Monticello is one of the great buildings of the country," Hosey said of the former president's home and architectural masterpiece. "There are so many interesting stories here, the opportunity is just overwhelming." He explained how his study of the rich burial traditions of the slaves also deeply informed his submission.

Hosey's

design concept—which he continues to develop—calls for a circle of stone

markers that appear as if they are emerging from the ground. The markers

themselves would be split at the top to represent the custom of leaving

pieces of broken pottery on a gravesite.

Hosey's

design concept—which he continues to develop—calls for a circle of stone

markers that appear as if they are emerging from the ground. The markers

themselves would be split at the top to represent the custom of leaving

pieces of broken pottery on a gravesite.

He said his research led him to learn about how African American slaves in this country in particular saw death as a form of liberation, "because their religious faith allowed them to believe that the next life would be where their freedom was attained." One of the specific customs he is referencing by splitting the stones, he said, is the slave's practice of leaving fragments of clay pottery to "symbolize the breaking of the body and the release of the spirit from the body."

The placement of the stones in a circle is also derived from historical and cultural behavior. He said, "Most historians seem to think that the idea of standing stones in a circle to mark a sacred ground began in [West Africa], where most of the slaves in the Southeast in the plantation areas would have originated. So even though now we associate it with other cultures, there is an argument that it began there."

"On

another level," Hosey said, "I'm hoping to portray the markers

in such a way that they're surrogates for the body . . . If you see these

markers as being people standing in a circle, then it also relates to

spiritual and other gatherings."

"On

another level," Hosey said, "I'm hoping to portray the markers

in such a way that they're surrogates for the body . . . If you see these

markers as being people standing in a circle, then it also relates to

spiritual and other gatherings."

He noted that slaves would often gather in circles when they were singing, dancing, or taking part in religious activities because their meetings would happen "in secret, in the woods, out of sight, and most often at night, which is when the funerals would take place."

The design, he said, also represents the slaves' connection with the land. "It's part of the reference to plowed or furrowed earth, because it is a plantation and most of the work was agricultural," he said. "The top of the stone gradually emerges out of the ground and its shape suggests that it is being released from the earth. There is this combination of being rooted and released."

Hosey noted that the architects and Foundation planners are still at the beginning of the process. The next step will be the formation of an advisory panel that will devise guidelines for site planning and the development of the memorial. There is no completion date set.

Two designs, one

memorial

The cemetery, which is about 65 ft x 75 ft, is on wooded land about 2,000

feet from the main house. Hosey said the landscape architect's design

proposed connecting the memorial to a larger network of pathways leading

down from the house to the memorial site. The paths would be planted with

native trees and paved and marked intermittently with stones.

Merging the two plans prevents the memorial from becoming an "isolated" event, Hosey said. "It's connected to the larger community and the larger network in the mountains, so it really feels like it is a part of what's going on there."

The

site was identified in 2001, and is the first slave cemetery to be identified

at Monticello. The Foundation has since reported that the graves were

not disturbed and that no remains were disinterred during the archaeological

work, which identified the burials of 20 adults and children. It also

notes that statistical models indicated that the site contains at least

40 graves.

The

site was identified in 2001, and is the first slave cemetery to be identified

at Monticello. The Foundation has since reported that the graves were

not disturbed and that no remains were disinterred during the archaeological

work, which identified the burials of 20 adults and children. It also

notes that statistical models indicated that the site contains at least

40 graves.

Hosey, an award-winning architect who is working on this project on his own time, said his firm is supportive of his efforts. He noted that the principal of his firm, William McDonough, FAIA, was dean of the University of Virginia's school of architecture and often draws upon Jefferson's writings when he speaks about the firm's work, which focuses on balancing architecture and the environment.

Hosey received a $1,000 honorarium. Towson and Sherry will share a $1,000 honorarium.

Copyright 2002 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved.

![]()

|

Read more about Monticello and its history. Thomas Jefferson's Monticello, published by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc. (2002) features a collection of essays and color photography that showcase the former president's Charlottesville home. You can order Thomas Jefferson's Monticello from the AIA Bookstore, ($40.50 AIA members/$45 retail, plus $6 shipping per order): phone 800-242-3837 option #4; fax 202-626-7519; or send an email. |

|