by Rick Harlan Schneider, AIA

The Girard Street Playground was a symbol of despair in 1998. With blind alleys and abandoned buildings handy for evading the law, the one-acre site had become a hangout for drug dealers. Then came three murders in a row. The community wanted to do something. A local planning and design firm showed them how.

My partner, Mike Hill, is a member of the All Souls Unitarian Church, which is less than two blocks from the playground. In fact, years ago, the church owned that property. So when the congregation rallied around the Rev. John De Taeye and other community leaders to form Friends of Girard Street Playground, our firm had a vested interest.

The group had influential and well-connected members, which drew backing from D.C. City Council Member Jim Graham, Congressional Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton (D), the D.C. Department of Recreation and Parks (Parks&Rec), and the National Endowment for the Arts, among many others. We all brought the cumulative resources of this group to bear on the problem of bringing back the playground.

How long does it take to build a playground? Three months? With completion expected this fall or winter, the answer is closer to three years. There was certainly a share of delays that normally accompany an effort of this size: organizing support, harnessing the power of large bureaucracies, planning a $1.7 million renovation project, and, of course, finding $1.7 million to invest in an underserved community. A lot of the delay, though, was not really delay. It was hard work by many people to create a self-driving community center; to create a sense of community.

Community

by design

Community

by design

Mike and I got involved through his connection with the church, and we

offered Friends of Girard Street Playground our services in helping them

envision what could happen there. We began with a preconcept exercise

we call the community design process, a series of workshops to give voice

to people in the neighborhood and give them a sense that something was

really going to happen.

Parks&Rec agreed to split the cost of the first workshops, which was about $1,500. And we did a lot of pro bono work at first. Later, with support from the NEA, we were able to get paid for our services. That was never our motivation. Our firm's goal, which we state right up front on our Web site, is "to improve the quality of life for people by improving the places we inhabit." In this playground project, we're doing what we believe.

From the first workshop in February 2000, we came up with three vision schemes and a report highlighting the issues people identified. They wanted a playground with a community center and that would stimulate development. The plan drew attention. For instance, the city subsequently agreed to purchase the two abandoned buildings on the northwest side of the property. As neighbors began to realize they can make a difference, they started volunteering to clean up the playground itself, along with the maintenance Parks&Rec provided. We had cleanup sessions. It was really great, and istudiodesign got to be a part of that as well to show them that we were not just designers who step in and say "Here's what you ought to do here."

That first report also cemented financial support from the NEA and Parks&Rec because it showed the group was organized and the community had some vision and direction. With invaluable help from Parks&Rec, we were able to secure a $285,000 Urban Park and Recreation Recovery Program grant from the U.S. Department of Interior.

Getting

specific

Getting

specific

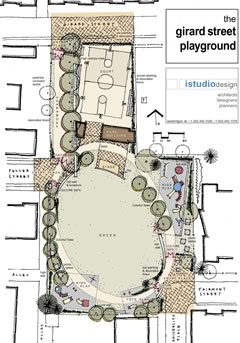

The second round of design workshops came up in September and October

of 2000. About 100 people from the neighborhood, plus local community

groups and local government attended. We took the three vision schemes

and honed them into one single overall vision that touched on key issues

of multiculturalism (this area is probably one of the most culturally

diverse neighborhoods in the city), safety, and mixed uses. We started

getting specific: an active side with a basketball court; a side for passive

recreation, including an area for toddlers; and a wide, flexible-use greenspace

in between. People wanted a community center literally at the center of

this site as a focal point, including a place for performing arts.

Some of the ways we encouraged broad community participation included providing child-care services on the days of the workshop, which was a big draw for young parents who otherwise wouldn't be able to attend. We had different group activities for parents, young adults, and children, which really involved everyone in the process.

During the long planning process, to give a sense of progress and results, we implemented some interim projects in the playground. We designed a couple of storage facilities for recreation equipment, paths, a new fence, picnic benches and tables, some plantings by a local community group, a kiosk by Shaw Ecovillage (which teaches kids how to build Green), and a really nice canopy, which people see as announcements of change. And the neighbors are watching after the park. If Parks&Rec weren't able to get to the site to mow or water, people across the street would mow or take out a garden hose. So people are starting to pick up the ball now.

We have now finished the conceptual plan, and Parks&Rec has hired an architect to create the construction documents and administer the construction contract. They have broken ground.

Environmental

safety, too

Environmental

safety, too

The idea here with this playground was not just to make it safe for people

but also to make it environmentally friendly. The community center, for

example, will incorporate both new and existing environmentally sustainable

technologies, which will make the facility cleaner and help educate people

in the community. So the facility itself starts to become a teacher. The

community center will incorporate solar panels, recycled materials, and

certified wood. The playground will have a recycling center.

All in all, the community got a unified and well-documented vision that is easy to understand. Moreover, they have built a constituency for change in the neighborhood and a community structure that will help them solve other problems in the future. So the playground has served as a catalyst for change. Beyond its boundaries, the playground has touched on adjacent properties, view corridors, and the street front. It has become a symbol of pride and hope.

Copyright 2002 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved.

![]()

|

Rick Harlan Schneider is a partner in istudiodesign in Washington, D.C, which specializes in Green planning and design. He is also active in the AIADC Committee on the Environment. Got a BEST PRACTICES tip on any subject that you'd like to share with your peers via AIArchitect This Week? Send an email to Managing Editor Stephanie Stubbs and tell her what it's about. We'll get in touch—we'll even write it for you! |

|