AIArchitect asked founder Cameron Sinclair how Architecture for Humanity got its start? Here's his answer.

I guess it really began when I was at in University of Westminster and the Bartlett School of Architecture getting my education. I became intrigued in social, cultural, and humanitarian design. By the time I started my post-graduate work, I was drawn toward studying the housing of large numbers of displaced populations—whether they be nomadic, refugee, or homeless. My thesis focused on the housing of New York's homeless population through sustainable and transitional housing.

Naturally,

I moved to New York City and, like most graduates with debts to pay, took

a job as a designer. Within four years of working, I realized I had worked

on projects in over 20 countries. It seemed to me that as a profession

that benefits from working internationally, we have a level of social

responsibility globally.

Naturally,

I moved to New York City and, like most graduates with debts to pay, took

a job as a designer. Within four years of working, I realized I had worked

on projects in over 20 countries. It seemed to me that as a profession

that benefits from working internationally, we have a level of social

responsibility globally.

At the same time, I was also helping run a film festival in New York and got the opportunity to view an English documentary called "The Valley." This film was a six-week journey within the epicenter of the Kosovar conflict. The filmmaker, Dan Reed, spent time with both Ethnic Albanians and Serbs fighting each other for control of this valley.

The two things I came away with from watching the film were the destruction of homes through scorched-earth tactics and the determination of the residents to return—no matter what. Within a couple of weeks, NATO and the Allied Forces were pounding Kosovo with aerial bombardment. All we heard on CNN was "the end game'" and "our tactical goal." The last thing discussed was how the hundreds of thousands of displaced residents would return and rebuild their war-torn country. It came to me that five-year transitional housing could be built next to the existing homes of returning refugees and shelter them as they rebuilt their existing homes.

The first thing I did was team up with War Child USA, a charity working within the refugee camps, to get a direct communication set up with refugees and compile a team of relief experts from non-government agencies (NGOs), the United National High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the U.S. Agency for International Development. Together we created design criteria, and Lauster/Radu Architects (the firm I worked for) wrote up the submission requirements.

Within six weeks of the idea, and with the help of Bianca Jagger, a War Child patron, we launched the competition at the Van Alen Institute. Although participants had only three months to submit ideas, the Web site received more than 50,000 visits, and we collected more than 200 entries from 30 countries.

Our

jury, half architects (Billie Tsien, AIA; Tod Williams, FAIA; and Steven

Holl, AIA) and half relief organization and NGO representatives), selected

10 finalists. These finalists and an additional 20 selected entries were

exhibited in four countries and featured in more than 30 newspapers and

design publications. Publicity from these exhibitions helped to raise

donations for War Child and—along with all the proceeds from the

submission fee—create housing, schools, and medical facilities in

Bosnia, Kosovo, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and other war-torn areas. Prototypes

of two winning entries have already been built. Two more are currently

in development.

Our

jury, half architects (Billie Tsien, AIA; Tod Williams, FAIA; and Steven

Holl, AIA) and half relief organization and NGO representatives), selected

10 finalists. These finalists and an additional 20 selected entries were

exhibited in four countries and featured in more than 30 newspapers and

design publications. Publicity from these exhibitions helped to raise

donations for War Child and—along with all the proceeds from the

submission fee—create housing, schools, and medical facilities in

Bosnia, Kosovo, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and other war-torn areas. Prototypes

of two winning entries have already been built. Two more are currently

in development.

While the jury was meeting, I went on my honeymoon to South Africa, supposedly to relax. Of course, within a day I was looking at the housing crisis and helping my wife, a journalist, on a story on rape in South Africa (which, at close to 1 in 3, has one of the highest levels of reported rape in the world). During my housing visits, the prevalence of HIV/AIDS kept surfacing. In areas in Zulu-Natal, some villages have more than 80 percent infection rates. In the whole of South Africa, within 10 years, close to one in four people are expected to die.

Most of the doctors we met stated that one of the major problems affecting the treatment of this pandemic was the lack of adequately equipped facilities to reach the huge rural population and give basic testing, prevention, and treatment—let alone distributing information regarding the virus. One doctor told me about the sterilization equipment they used that was supposed to be plugged in to sterilize reusable needles. Where in the middle of the rural Africa is there a convenient duplex in which to plug in your sterilizer?!

Inevitably, someone had scrawled "DEATH" across the top of the equipment to remind other doctors not to use it. This is one of a hundred stories I heard, and by the end of my trip it was painfully apparent that designers could do something about this. Individually, we won't save one life. But by using our talents we can create a highly efficient mobile unit to give trained medical professionals the best opportunity to save millions.

Copyright 2002 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved.

![]()

|

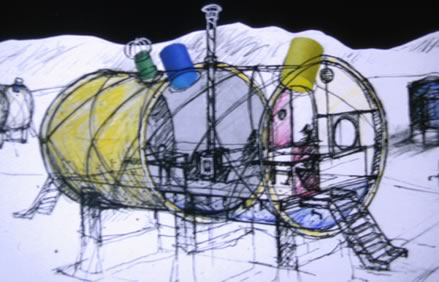

Click here to visit Architecture for Humanity. This design [left], a competition finalist, is by basak altan design. |

|