by Jane Thompson, AICP, Assoc. AIA

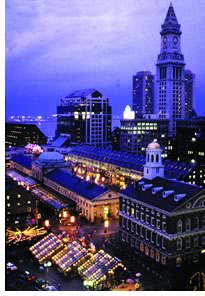

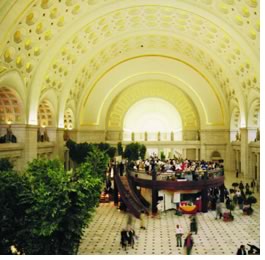

The grande dame of regional revitalization through landmark restoration offers her thoughts on what it takes to bring a landmark building back to life. Principal of Boston's Thompson Design Group, Jane Thompson, AICP, Assoc. AIA, has worked—along with her husband, 1992 AIA Gold Medalist Benjamin Thompson, FAIA—on phenomenal commercial and building-restoration successes that include Boston's Faneuil Hall and the District of Columbia's Union Station. Thompson offers her insight on what it takes to make a restoration work, including her thoughts on the TWA Terminal in New York City and the World Trade Center site.

A lot of people today are on a preservation kick wherein they define preservation in the most rigid way possible. In fact, it seems to be getting more rigid as time goes on. This is worse, not better. When someone looks only at preserving the building itself—the shell—and doesn't think anything about uses that will keep that building going—the interactive experience—then the building is going to continue deteriorating. Union Station is a perfect example. We looked at how that whole area of Washington could be revitalized through existing connections—the train station and adjacent subway system—as well as through planning beyond the project for the area around the station.

To

make that station work, we designed in stores, restaurants, a theater,

and a food court to make this transportation hub into a destination of

its own. And we drew a lot of criticism. Still, we were lucky to get through

it when we did because as tough as it was in Washington in those days,

it's probably twice as bad now. The same is true for Boston. If we were

going to do Faneuil Hall again, I don't think we'd be allowed to.

To

make that station work, we designed in stores, restaurants, a theater,

and a food court to make this transportation hub into a destination of

its own. And we drew a lot of criticism. Still, we were lucky to get through

it when we did because as tough as it was in Washington in those days,

it's probably twice as bad now. The same is true for Boston. If we were

going to do Faneuil Hall again, I don't think we'd be allowed to.

To restore value,

restore use

You have to reuse a building in the most intelligent possible way. You

simply cannot make a museum out of every building that you like. You always

strive to keep its qualities and then make it do more than it has been.

A landmark in decline is obviously not doing the right things—even

if it's still doing what it was originally designed to do. Maybe it's

declining exactly because it's

still performing its original function.

With regard to the TWA Terminal at JFK Airport, as one example, I think there are many ways that the building can serve the traveling public and the needs of the airport without being cast into this mode of "It's a monument. It cannot be altered." I'd say you could both restore its value and vigor and maintain the visual impact that Saarinen intended. Many people don't believe that, though. So we'll see what happens.

I hate the monumental approach to landmark restoration, because it usually fails. And it fails because there's no economic basis that will pay for the saving of the building, which is so expensive. Or they fail because once they're there, they have very little purpose and cost a lot to maintain.

Another example is the Old Post Office Building in Washington, D.C. We recommended years ago when its very existence was in question that it be converted into a hotel. Arthur Cotton Moore, who got the commission, has said that he also proposed using the space for hotel rooms. The General Services Administration (GSA) was rigid about needing office space at that time, though. They had a very different agenda and forced the building to the mold that was going to work for them. And then they undermined it by putting a federal-facility cut-rate cafeteria right next door. They hadn't thought the solution through in terms of the Old Post Office's connection to its location and surroundings.

Who

decides?

Who

decides?

The debate over what is going to happen on the World Trade Center site

is a terribly dramatic example of what you often see—obviously to a much

smaller degree—in landmark restoration projects everywhere. There

is a public forum, which generally takes care of itself, getting more

intelligent and constructive as time goes on. And, because it has to do

with a building, and a crisis, you are going to get architects who jump

in and say, "I can design the answer." They don't stop to think

about the harder issues or all the people involved. So they love to have

competitions. As we are seeing with the Lower Manhattan debate, people

soon enough get all of that out of the way. There have been some very

intelligent meetings, and a lot of this ego stuff is beginning to evaporate.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey—the World Trade Center owner—is working closely with the regional planning association since the beginning to figure out how to restructure this space so that it maximizes the beneficial impact on Lower Manhattan. There are so many things that can come out of this. The solution will not be only about replacing those buildings. It's about all the streets and the problems that are there and can be greatly improved in the whole planning and rebuilding process.

Of course, everybody sees that you have to have a memorial there. But it is not 14 acres of memorial. That is an important part, but only one part of a whole new complex. And I think we see now that it doesn't have to be duplicating what was there before. It can be a community with a whole different set of design purposes or mix of purposes. So let's look at the streets and traffic patterns, make it more pedestrian friendly, give it more open space. And tie it in to everything that's already going on, for instance the system upgrade that ConEd just happens to be undertaking right now, tearing up and replacing every street in the city.

Bringing together all the elements at work is the key to the success of any redevelopment.

Copyright 2002 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved.

![]()

|

For an overview of the Historic Resources Committee's "Public Architecture + Historic Preservation + Private Enterprise = Urban Revitalization" conference, March 8–10, in Washington, D.C.—plus case studies of public/private partnerships—visit the PIA Gateway. If you would like to explore how public agencies and private-sector developers and owners are tracking capital projects based on scope, schedule, financials, and overall condition and status, sign up for the "Owner/Client Enterprise Program" seminar (SA 16, May 11, 2–3:30 p.m.) at the AIA national convention in Charlotte, May 9 to 11. For complete convention information, visit the AIA convention Web site. |

|