Every Client Should Feel Like Your Only Client

by

William Higgins, AIA

by

William Higgins, AIA

It may sound simple, but the key to a successful international practice is to provide complete service and let your clients know that they are your first concern, always. I find that true in our practice and I see it in the practices of my colleagues on the International Committee.

Personal

commitment

Personal

commitment

Part of our professional commitment and the fulfillment that comes with

it is developing personal relationships with our clients. An example is

the 15-year relationship we have with one particular client in the Philippines.

In that time we’ve created friends in that organization from the

president and chairman of the board to the project managers. And the friendship

extends beyond the business level. We exchange holiday cards and gifts.

If there is a natural disaster or political crisis, we call to see if

they are all right. Trust is built on genuine concern.

On the professional level, our principals commit to each project and remain active in the design and at meetings. We take on the responsibility of participating here in the office—communicating directly with the project team members overseas—and we will jump on a plane at a moment’s notice. We don’t get the job and pass those responsibilities on to a surrogate. One result is that the client always turns to us as a person; someone they know they can trust to give them our best effort.

The commitment is long-term, not just for the project at hand. It’s also a larger commitment than the client alone. In the case of the Philippines, you could say it is a commitment to the entire country. You have to respect their culture. You have to respect your clients’ position within their society and how they got to where they are. You have to learn the politics and customs of the country so you can be sensitive to the struggles that they’re going through.

Another

part of developing mutual respect is sharing knowledge. We develop an

understanding of the good our clients are trying to do for their country

in their projects, and we help them develop something that has a social

conscience to it. We learn from them as much as they learn from us.

Another

part of developing mutual respect is sharing knowledge. We develop an

understanding of the good our clients are trying to do for their country

in their projects, and we help them develop something that has a social

conscience to it. We learn from them as much as they learn from us.

All this commitment to service does take a toll on you, because you have to be very responsive. When they call, you need to jump so they know that you’re working for them. We’re a fairly small firm without branch offices overseas, so we overcome that with the commitment of being available, whether it’s by phone, fax, e-mail, or plane; whether they come here or we go there.

Networks open doors

When my two partners and I started Architecture International, we had

a network of people we’d worked with in our past who had since moved

to countries such as Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines. In lieu of offices

in those countries, we made these collegial relationships and worked together

to find projects. They were our eyes on the ground. A big part of doing

international work is the partnering you do. If we’re doing a project

in the Philippines, we partner with a local Filipino architectural office.

They become your partner and you then have a larger office, albeit virtually.

An interesting offshoot of working in that region is that you get into

the whole 24/7 scenario because of the time change. We have our eight-hour

day, then they have their eight-hour day. With instant telecommunications,

that’s a benefit because we can exchange drawings at each of our

day’s end and be turning out work almost constantly.

Our

previous experience working at The Architects Collaborative was essential

to the success of Architecture International. At the time, TAC was known

mostly for its work in the Middle East, but they were expanding worldwide

and had gotten into the Philippines by going on a trade mission in the

1970s. Their first project was a modest resort planning study, which led

to another government-sponsored project. One of my first projects at TAC

as a designer was a large headquarters building right on Manila Bay in

the early 1980s. Working with a local architect, we incorporated cultural

and climatic influences and ended up doing what would now be called green

building solutions, with passive solar, day lighting, natural ventilation,

and recycled rain water. We were learning from their vernacular and construction

methods and developing key contacts at the same time.

Our

previous experience working at The Architects Collaborative was essential

to the success of Architecture International. At the time, TAC was known

mostly for its work in the Middle East, but they were expanding worldwide

and had gotten into the Philippines by going on a trade mission in the

1970s. Their first project was a modest resort planning study, which led

to another government-sponsored project. One of my first projects at TAC

as a designer was a large headquarters building right on Manila Bay in

the early 1980s. Working with a local architect, we incorporated cultural

and climatic influences and ended up doing what would now be called green

building solutions, with passive solar, day lighting, natural ventilation,

and recycled rain water. We were learning from their vernacular and construction

methods and developing key contacts at the same time.

That project won some awards, which was a huge point of pride for the Filipino architectural community, even for architects there who weren’t directly involved. So when we departed TAC and started Architecture International, we had the knowledge of the culture and continued to communicate with the people we knew in the Philippines, and that helped launch our first project, a small design study for Ayala Land Inc. that has become a mutually beneficial long-term relationship.

I

have talked with clients—ours and other people’s—who

tell me that during the Asian boom, all sorts of U.S. firms were there

looking for work, handing out their literature. But as soon as the boom

went away, most of these firms disappeared from the scene. That’s

a mistake that a lot of U.S. architects make. Building a working relationship

takes a commitment in the lean times as well as the booms.

I

have talked with clients—ours and other people’s—who

tell me that during the Asian boom, all sorts of U.S. firms were there

looking for work, handing out their literature. But as soon as the boom

went away, most of these firms disappeared from the scene. That’s

a mistake that a lot of U.S. architects make. Building a working relationship

takes a commitment in the lean times as well as the booms.

We use our connections to introduce our overseas clients to development opportunities, financial institutions, and potential tenants here in the U.S. And they reciprocate by introducing us to new clients in the Philippines. So having a trusting relationship as we do turns out to be a marketing tool as well, although it’s one you could never measure.

Sharing professional knowledge benefits

everyone

We make it a point to cater to our client’s needs when they come

to the U.S. We even help with their travel plans. More importantly, though,

because a lot of our clients want a better understanding of U.S. expertise

and Western ideas, we help them gain it. We tour facilities; not just

our projects, but a wide range of building types and styles. We’ll

buy books for them to help them understand a particular approach or system.

Clients see the value of our efforts to improve their understanding and

broaden their horizon of opportunities. They always want to see the latest

design trends in retail, residential, and other facility types. We don’t

hesitate to take the time to share that knowledge with them.

When

we first started working in the Philippines, we found some client frustration

that they couldn’t get the design expertise they wanted locally.

We took it upon ourselves to transfer our knowledge to the Filipino design

professionals with whom we worked. We have given lectures on design process

and technology to the local association of architects as well as to the

staff of the development firms with which we work. Again, it’s hard

to measure, but I believe we have helped elevate the profession in that

part of the world. The benefit we derive includes being able to work with

more responsive local professionals who understand the need for attention

to detail, coordination, and problem-solving.

When

we first started working in the Philippines, we found some client frustration

that they couldn’t get the design expertise they wanted locally.

We took it upon ourselves to transfer our knowledge to the Filipino design

professionals with whom we worked. We have given lectures on design process

and technology to the local association of architects as well as to the

staff of the development firms with which we work. Again, it’s hard

to measure, but I believe we have helped elevate the profession in that

part of the world. The benefit we derive includes being able to work with

more responsive local professionals who understand the need for attention

to detail, coordination, and problem-solving.

Act the part as an AIA member

When you help others, you help yourself. That’s an important lesson

I am reminded of often as chair of the national AIA International Committee

and from being very active in the San Francisco International Committee.

It’s an ongoing, long-term ideal. Service to the client is one of

the main components of the AIA’s professional edict. And I think

you have to carry that into your work internationally.

Copyright 2004 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

| Bill Higgins,

a founding principal of Architecture

International, is the 2004 chair of the AIA International Committee.

For information on the 2004 International Committee conference,

“International Practice Issues: Cross Cultural Partnerships,”

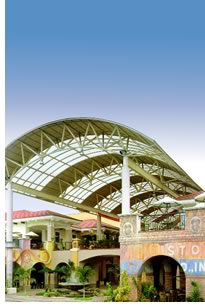

October 2 in New York City, visit AIA.org. The award-winning Alabang Town Center is just one project Architecture International has designed for Ayala Land Inc., the premier development company in the Philippines. Adjacent to the Catholic church in this Spanish-Filipino community, the town center has become part of the local social fabric, the “living room of the community.” After Sunday Mass, families gravitate to the retail center and town plaza for shopping and lunch. The plaza also serves as a stage set for performances. Photos courtesy Architecture International. The AIA collects and disseminates Best Practices as a service to AIA members without endorsement or recommendation. Appropriate use of the information provided is the responsibility of the reader.

|

||